Inequality gaps in coverage of at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine between ethnic and socioeconomic groups in older adults in Wales have narrowed slightly since March, however inequalities in younger age groups have widened.

These are the latest findings from Public Health Wales (PHW). Since February PHW has published monthly reports on inequalities in vaccination uptake which provides a breakdown of those who have received first and second doses of a vaccine by ethnic group, deprivation quintile, sex and age.

This article is an update of our article from March: ‘Who’s being left behind in the vaccine rollout?’. We publish weekly updates on vaccination data which outlines who has received a first and second dose by priority groups across Wales, Local Health Board and local authority.

Who’s still at risk?

Before the vaccine rollout began concerns were raised by public health experts that vaccine uptake could be lower among some ethnic groups. Others warned that the vaccination programme could further entrench existing inequalities.

In March the Welsh Government published a vaccination equity strategy which stated that a new Vaccine Equity Committee would “ensure the equitable delivery of the vaccination programme”. In June the Government published an updated vaccination strategy which says it operates a “no one left behind principle”.

As COVID-19 cases rise, communities and groups of people with lower uptake will be particularly at risk from the virus.

Public Health England (PHE) has found that one dose of a vaccine is 17% less effective at preventing illness from the Delta variant (originated in India) compared to the Alpha variant (originated in Kent, UK). Therefore, we know that second doses are needed to achieve a higher rate of effectiveness and protection.

People from some ethnic groups

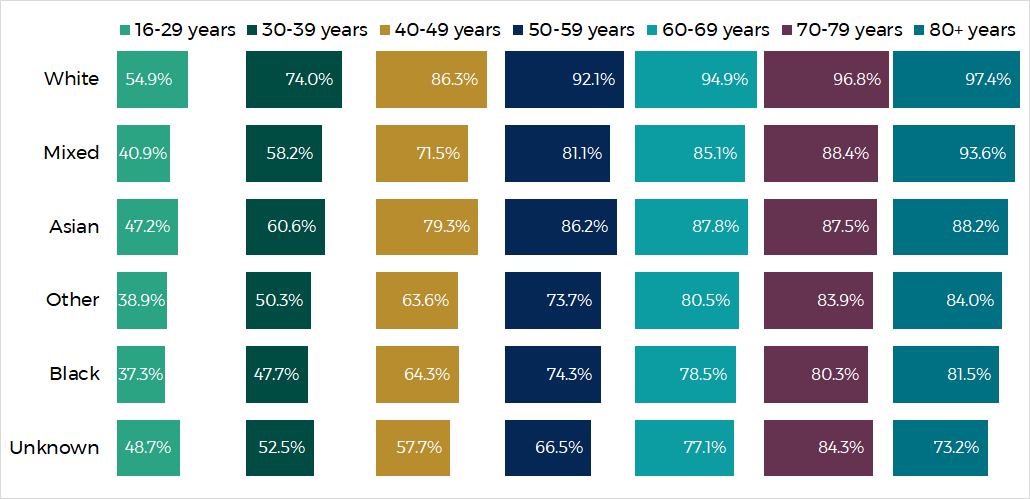

The graph below shows that the uptake of those aged 30-39 in the Black ethnic group is 26.3 percentage points lower than those aged 30-39 in the White ethnic group.

Uptake of one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and ethnic group

Source: Public Health Wales

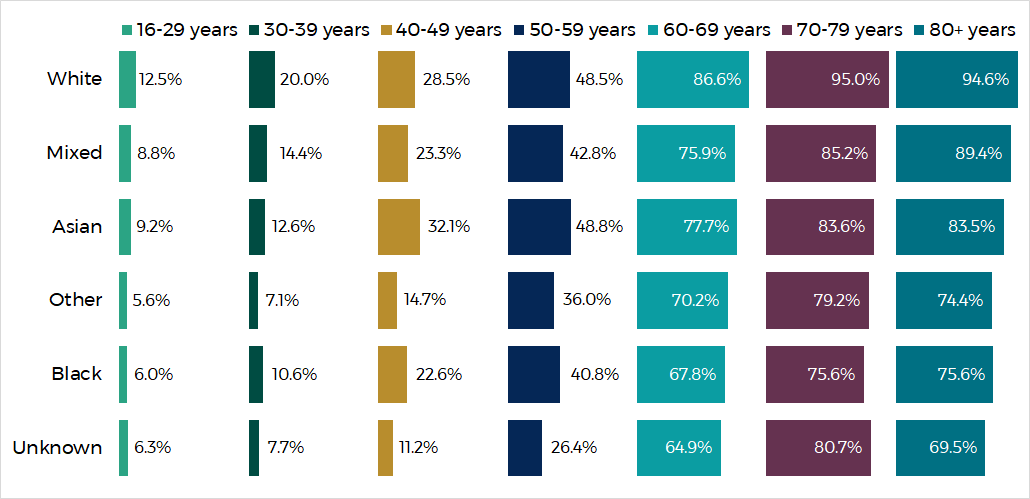

While the rollout of second doses is still very much in progress, the data so far already shows a similar pattern of differences between ethnic groups as seen in the graph below.

Uptake of two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and ethnic group

Source: Public Health Wales

People living in the most deprived areas

PHW’s report highlights that “inequalities continue to be seen between adults living in the most and least deprived areas”.

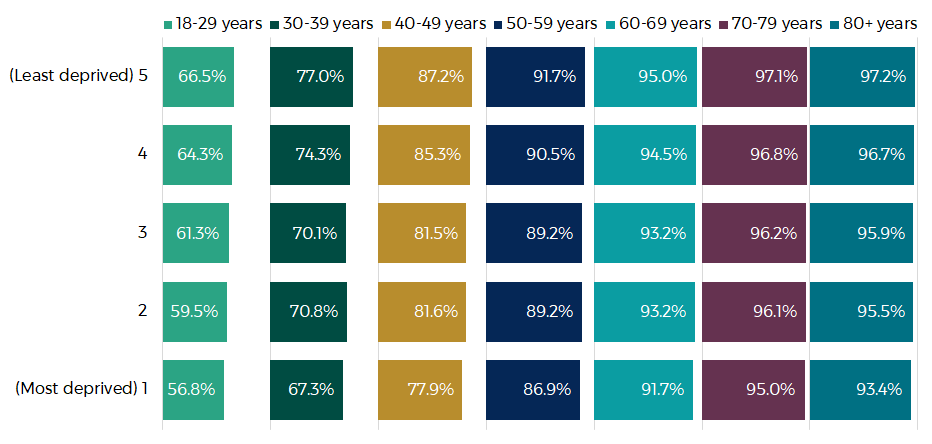

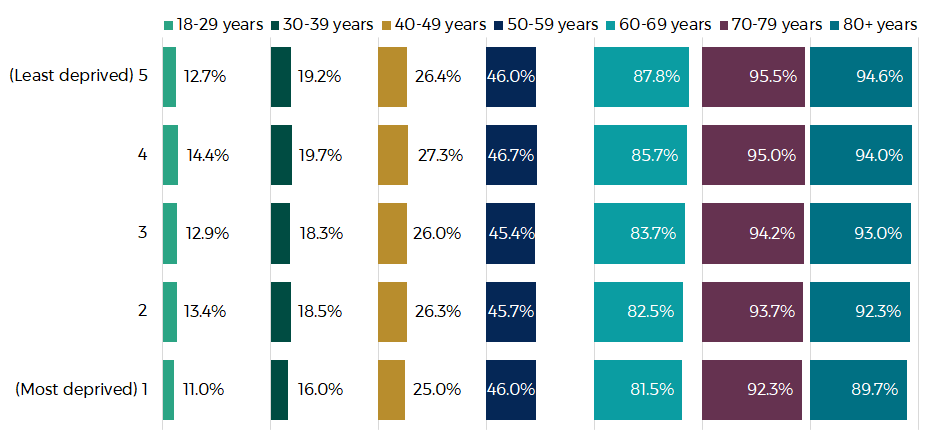

The two graphs below show uptake by age group and areas of deprivation measured by the Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD). WIMD is an overall measure of deprivation based on a number of factors such as income, employment, health and education.

The graph below shows that the biggest differences in uptake of first doses is in those under the age of 50. In the 18-29, 30-39 and 40-49 age groups there are around 10 percentage points difference between the most and least deprived areas.

Uptake of one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and WIMD quintile of deprivation of area of residence

Source: Public Health Wales

Uptake of two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and WIMD quintile of deprivation of area of residence

Source: Public Health Wales

Males

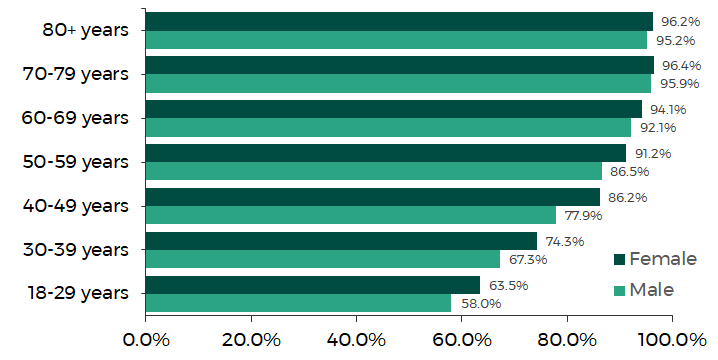

PHW’s report notes differences in vaccine coverage between those with a recorded sex of male or female.

The graph below shows that uptake in males below the age of 60 is particularly lower than in females. The largest gap is 8.3 percentage points difference between males and females in the 40-49 age group.

Uptake of at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and sex

Source: Public Health Wales

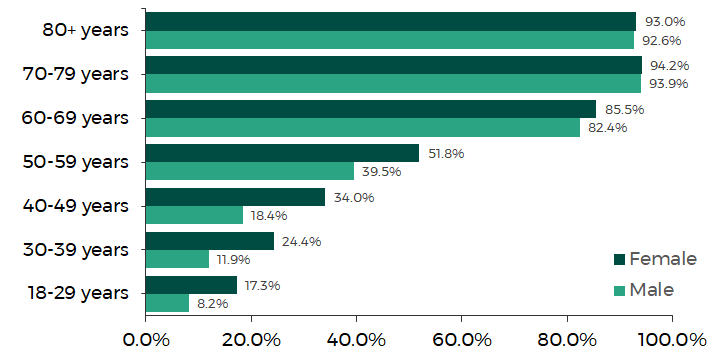

The differences between the sexes becomes even more stark when looking at second doses, in particular in those below the age of 60.

Uptake of two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and sex

Source: Public Health Wales

Why might some people not take up the vaccine?

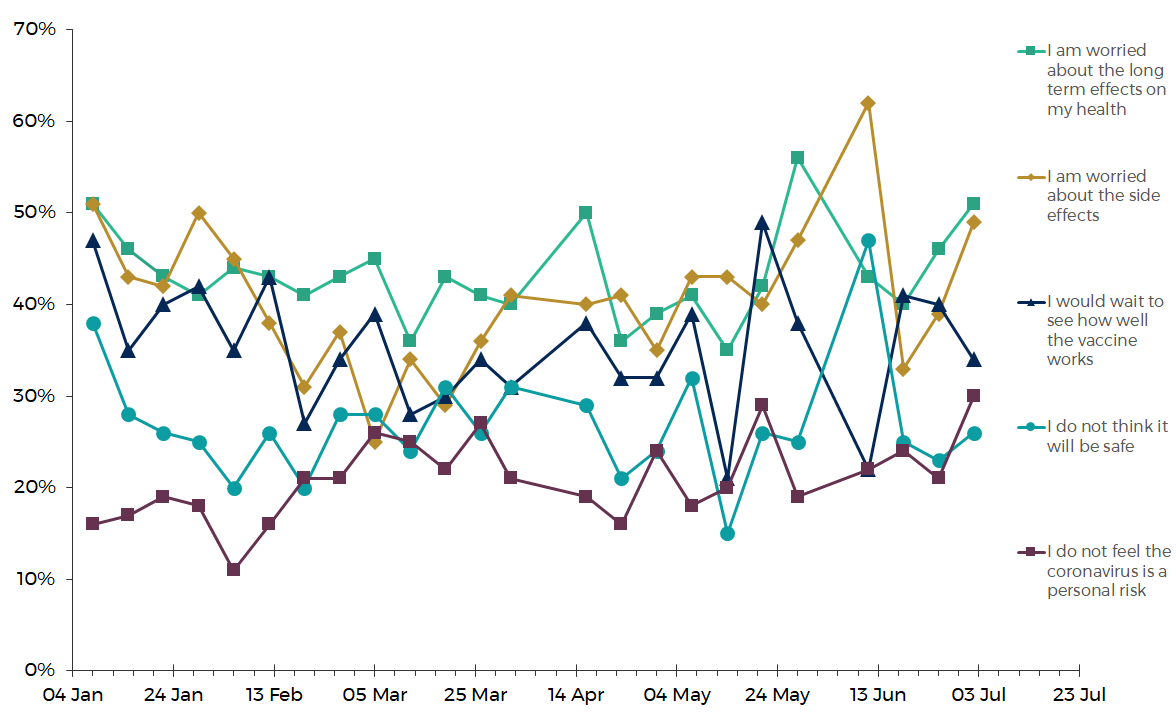

Since January 2021 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has included questions on reasons for not taking up a vaccine in its surveys aimed at understanding the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The graph below shows the five most common reasons reported over time and shows that the most common reason respondents said they didn’t want to receive a vaccine has frequently changed over the last five months.

As of 2 July, 51% of respondents said they were worried about the long term effects on their health and 49% reported being worried about the side effects.

Reasons for not taking a vaccine for COVID-19 if/when it is offered

Source: Office for National Statistics

Research by the ethnicity sub-group of the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) suggests that specific reasons for vaccine hesitancy among some ethnic groups include:

- low confidence in the vaccine;

- perception of risk;

- distrust of public authorities;

- inconvenience and access barriers;

- socio-demographic context and lack of endorsement, and

- lack of vaccine offer or lack of communication from trusted providers and community leaders.

Our guest article by Dr Simon Williams and Dr Kimberly Dienes of Swansea University explores vaccine hesitancy in Wales.

What’s being done to increase uptake in these groups?

In its updated vaccination strategy, the Welsh Government said that the NHS is reviewing data on those who don’t attend their vaccination appointment to “understand temporal and geographical patterns”. It says this allows “targeted communications to inform and enable people to take up their offer”.

The Welsh Government’s vaccination strategy included three milestones. The third was that all adults will have been offered a first dose of a vaccine by the end of July 2021. It said that after achieving this milestone, “there will be a specific period of focus on equality of coverage”. On 13 June 2021 the Welsh Government said that all adults will have been offered a first dose of a vaccine by 14 June.

The ethnicity sub-group of SAGE suggested some solutions to overcoming these barriers include:

- Improving trust through GPs and health centres by recommending and offering vaccines, and improving uptake among healthcare workers from all ethnic groups;

- Community engagement, including working with community leaders, providing public information about the MNRA process, educational videos in different languages, clear information on side effects, and disassociation from political figures;

- Addressing access and convenience issues at a local level, for example by providing vaccinations in workplaces, community centres, and religious venues, compensating financial loss (travel costs, or loss of earnings), providing support for booking appointments (including transport), and giving prompts and reminders for appointments; and

- Culturally tailored communication shared by trusted sources, including training for healthcare staff to enable conversations about vaccine beliefs, and training for faith leaders on vaccine research.

Article by Lucy Morgan, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament