Vaccine hesitancy is a complex issue and isn’t a simple matter of individual choice. But what is vaccine hesitancy, how big of an issue is it in Wales and what can be done to overcome it?

This guest article by Dr Simon Williams and Dr Kimberly Dienes of Swansea University explores these issues as part of our knowledge exchange programme. The views are that of the authors, not Senedd Research or the Senedd.

How many people have had a vaccine?

As of 30 June 2021 more than 70% of the Welsh population has received a first dose of a vaccine, with 53% of the population receiving second doses. In its updated vaccination strategy from June, the Welsh Government aimed to offer all adults a first dose by the end of July. It met this deadline six weeks early.

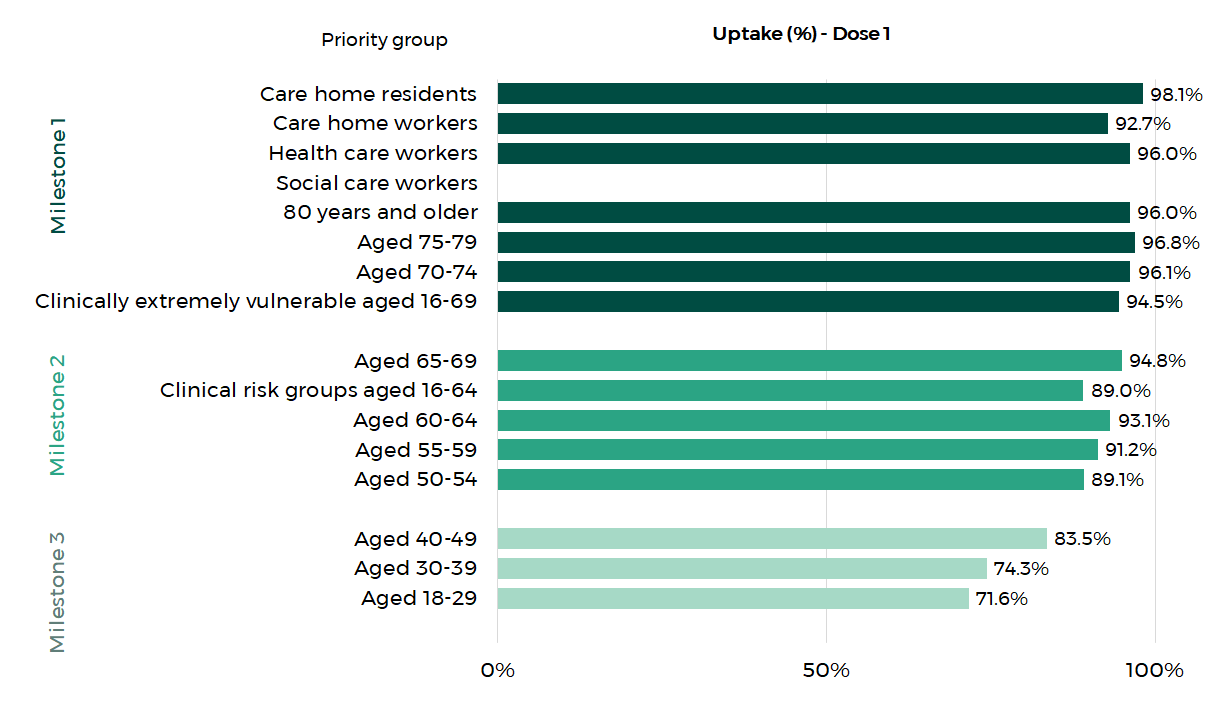

The Welsh Government aimed to reach 75% uptake of first doses in each of the priority groups by the end of July. One of the Welsh Government’s concerns was that vaccine uptake would be lower among “a younger and healthier population who will likely feel less at risk and potentially also have increased hesitancy”.

Recent data suggest that 71.6% of those aged 18-29 have taken up their offer of a first vaccination as of 30 June – a lower proportion than for older age groups. Although this may increase before the end of July.

Percentage of people who have received a first vaccine dose by priority group

Source: Public Health Wales

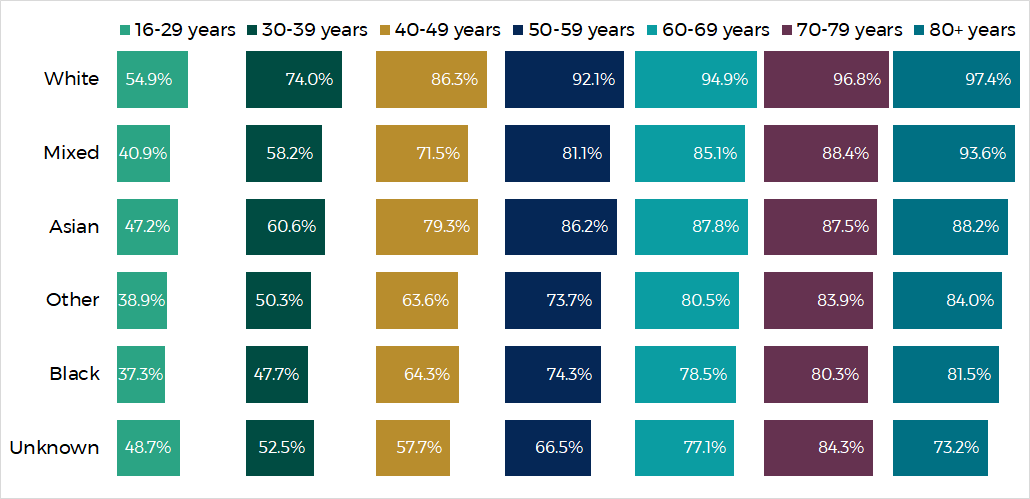

Additionally, we continue to see significant inequalities in uptake by ethnicity and socioeconomic background. Across all age groups, uptake by individuals from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups is lower compared to individuals of White ethnicity.

Uptake of one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine by age and ethnic group

Source: Public Health Wales

What is vaccine hesitancy?

Firstly, vaccine hesitancy is a multi-faceted issue and not a simple matter of individual choice. Rather, as the World Health Organisation’s Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants Matrix suggests, it is a complex interaction between historical, cultural, social and individual influences around vaccination in general, as well as those related to specific vaccines.

Secondly, contrary to how it is sometimes reflected in the media, vaccine hesitancy is not the same thing as anti-vaccination sentiment. The anti-vaccination movement, as the name suggests, tends to be strongly opposed to vaccination. But vaccine hesitants often have genuine concerns or questions about a vaccine’s safety, efficacy and whether it is being deployed in their interests before accepting it.

We tend to prefer the term ‘vaccine delay’, since it more accurately captures the fact that many of those who are yet to accept their invitation may be postponing their decision until they feel these questions or concerns are answered.

Why are some people more hesitant?

We are exploring public attitudes to COVID-19 vaccines in our Swansea University research (discussed in more depth in our full report), including some of the main reasons for vaccine delay.

Potential side effects are a major concern contributing to vaccine delay, something highlighted by the connection between Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine and blood clots. Many of those who reported wanting to delay the vaccine recognised that the risk of such side effects is extraordinarily low, but for some it nevertheless seeded doubt, or a preference to wait for a different vaccine

A lack of trust in those authorities responsible for developing and delivering the vaccines, including government, is a major factor contributing to vaccine delay. Although confidence in how the pandemic is being handled in Wales is relatively high, there remains an overall dissatisfaction for many people in the UK’s policy choices. There’s also an awareness that the UK has had one of the worst death rates amongst high-income countries. Among Black, Asian, and minority ethnic communities, distrust in political and scientific authorities might be particularly high, something that in part can be linked to systemic racism, according to a Welsh Government-commissioned report..

The lack of trust in government has helped conspiracy theories and misinformation to breed and spread, further fuelling vaccine hesitancy or delay. Research suggests that some, including people from some ethnic groups or economically deprived communities, might be drawn to conspiracy theories when they feel marginalised in society, perhaps because they have historically received unequal treatment. Conspiracy theories are often promoted by anti-government groups and therefore might be particularly appealing to those feeling disillusioned with the political system.

What can be done to overcome vaccine hesitancy?

It is important to both recognise the genuine concerns that are raised while simultaneously providing accurate information about risks and benefits. As well as working to overcome the barriers mentioned above, it is important to harness facilitators to uptake, especially for those groups most resistant.

For example, there is now an established social norm across society as a whole, towards vaccine uptake. Simple everyday acts, like reading about growing vaccination rates in the news or seeing ‘I’ve had my COVID-19 vaccine’ badges on social media can all help to spread and solidify this norm. Vicarious experience with vaccination, for example friends or relatives’ positive experiences of vaccination are also important. This is why involving influential members of those communities where uptake is lower is essential.

Finally, many people increasingly feel that vaccination it is the only way to get back to ‘normal’, and so for them the benefits outweigh any perceived risks.

Although the overall uptake is high, it is essential to engage with communities where uptake is lowest and hesitancy (or delay) is highest, if the Welsh Government’s 75% uptake target across all age groups is to be reached, and ideally surpassed.

Failing to address the lower uptake amongst those from some ethnic groups and the more deprived communities will likely mean that the already substantial COVID-19-related health inequalities that these communities face will get even wider in the future.

Every vaccination counts.

Article by Dr Simon Williams and Dr Kimberly Dienes of Swansea University

Dr Simon Williams is a Senior Lecturer in People and Organisation at Swansea University, Wales and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago.

Dr Kimberly Dienes is a Lecturer in Clinical and Health Psychology at Swansea University, Wales and a Honorary Lecturer at the Centre for Health Psychology at the University of Manchester.