This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

The Sixth Senedd will see the biggest change to land management policy in decades. What could this mean for rural communities and the natural environment?

Leaving the EU means Wales is able to develop novel agricultural schemes. Farming policy, which is devolved, has implications for the environment, economy and culture of Wales and has been a hot topic since the EU referendum.

The last Welsh Government proposed to fundamentally change farming policy to support wider sustainable land management, moving away from payment for food production in its own right. While environmentalists have welcomed this approach, tensions have risen in farming communities with the unions calling for payments for producing food. Future policy decisions will be made within a complex agri-food trading landscape and amidst the climate and nature emergencies.

Welsh farming statistics (figures are for 2018 or 2019, depending on the most current available)

Source: June Survey, Agriculture in the UK 2019, Welsh Government press release, Agriculture in Wales 2019 and Agriculture facts and figures: 2019.

Leaving the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy behind

The UK joined the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) in 1973. Originally, farmers received income to supplement prices paid for their produce to ensure food security and a good standard of living. But this encouraged overproduction, resulting in the notorious ‘wine lakes’ and ‘butter mountains’ of the late 20th century.

A major CAP reform in 2005 moved to payments broadly based on the area of land farmed. Farmers received direct payments (most recently through the Basic Payment Scheme (BPS)) and also support for rural development (for example the Glastir agri-environment scheme).

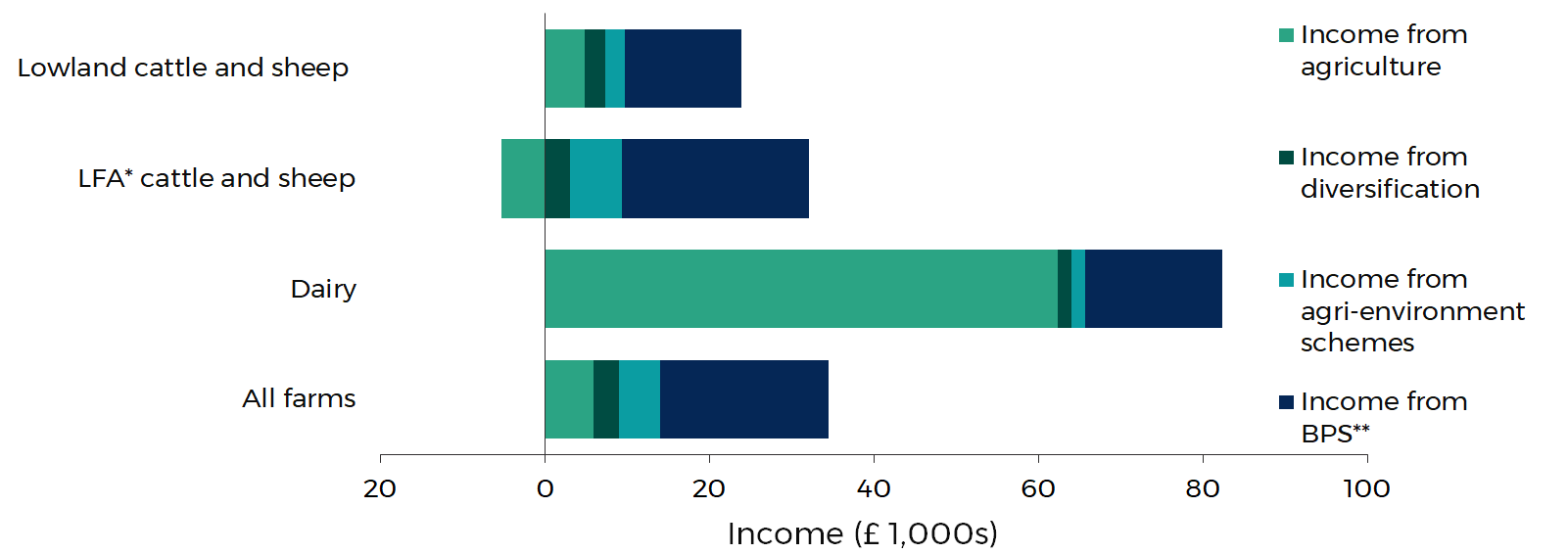

Many farmers in Wales have relied heavily on the CAP for income, particularly the BPS, more so than in any other UK country.

Farm income

* LFA = Less Favoured Area, ** BPS = Basic Payment Scheme

Source: Farm Business Survey (data as reported in Agriculture in Wales 2019)

Now the UK has left the CAP, an interim CAP-style system is being maintained under the UK Agriculture Act 2020 until Wales transitions to new domestic schemes. There has been disagreement between the Welsh Government and UK Governmentprevious Welsh Government and the UK Government over whether commitments to provide full replacement funding for the schemes have been met. This is due to different interpretations of ongoing EU funding being provided through the Rural Development Programme.

Some see exit from the CAP as an opportunity for radical change arguing that the CAP restricted environmental improvement, distributed payments unfairly (due to larger farms receiving more support) and was too complex.

Others remain cautious given the high reliance on BPS income and the uncertainty associated with leaving the EU and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Welsh Government published a White Paper in December 2020 for an Agriculture (Wales) Bill (planned for summer 2022) to establish new land management schemes.

A future farming policy based on public goods?

The White Paper proposals set out a very different and ambitious approach to agricultural support. Based on the principle of sustainable land management, the policy would reward farmers for providing ‘public goods’ from the land, including both social and environmental outcomes. The policy arguably goes beyond the CAP, supporting wider land management improvement.

Contrary to the CAP, farmers would not receive support specifically for producing food. The Welsh Government has argued that as food has a market value it should not be classed as a public good, and so should not be directly funded by the state.

Instead, funding would focus on the non-marketable benefits of sustainable food production such as enhancing biodiversity and carbon sequestration (capturing and storing carbon). This might be through enhancing wildflower diversity on farms or tree planting alongside food production.

Environmentalists have broadly welcomed the proposals highlighting the climate and nature emergencies. Some are calling for a quicker timeline for transition. Conversely, farmers are calling for food production to be eligible for support in its own right, holding concerns for the future of rural communities if this direct support is lost.

The new proposals may require farm diversification which many have welcomed to build business resilience. However academics have warned that farm businesses in Wales face several hurdles to diversification, such as poor upland land quality and remoteness from centres of population.

A new domestic and international trading landscape for the agri-food sector

The future agricultural policy will be developed in the context of new trade agreements. Farmers are calling for a trade strategy that seeks to both maximise access to overseas markets while safeguarding Wales’s high food and farming standards.

|

Agri-food trade statistics (by value) The latest information available is from 2019, before the UK left the EU Common Market. The UK agri-food sector relies heavily on foreign trade - in 2019 55% of food and drink consumed in the UK was produced in the UK. Imports: The EU has been the biggest source of the UK’s food and drink imports: 26% of food and drink consumed in the UK in 2019 came from the EU. The next biggest sources of food and drink imports were Africa, North America, South America, and Asia (each of these categories providing 4% of food consumed). Exports: The EU is also the UK’s biggest food export market at just under 60% of food and drink exports in 2019. Wales exports a greater proportion of its food and drink exports to the EU than the UK as a whole, at 75% of total Welsh food and drink exports in 2019. The top non-EU destinations for Welsh exports in 2019 were the USA, Turkey, Australia, Saudi Arabia and Canada. |

The previous Welsh Government envisioned a Welsh food brand based on environmental and social sustainability that would complement the public goods scheme for farmers. The Welsh Government’s ability to achieve these ambitions will be influenced by the UK Government’s decisions on international trade.

The UK Government says that new trade agreements could present opportunities for the agri-food sector. However some Welsh businesses are concerned about increased competition from imports with lower standards, as well as new barriers to trade between the UK and EU.

Lamb trade

Source: Adapted from Agriculture in Wales 2019

At a UK level, constitutional arrangements for policy divergence are becoming increasingly complex. Common frameworks and the UK internal market as well as the UK’s international obligations all limit the Welsh Government’s freedom to act in this area (see ‘Wales in the UK’ article.)

For example, the Internal Market Act 2020 will have significant implications for agri-food policy. Part 1 of the Act means that products that meet the standards in one part of the UK can automatically be sold anywhere else in the UK, even if the standards are different. This has sparked concerns that the rules of the largest market, England, will drive standards across the whole of the UK.

Developing a future farming policy amidst the climate and nature emergencies

The agricultural policy will be developed in the context of the climate emergency, declared by the Welsh Government and Senedd in 2019, and the nature crisis as described by the environment sector.

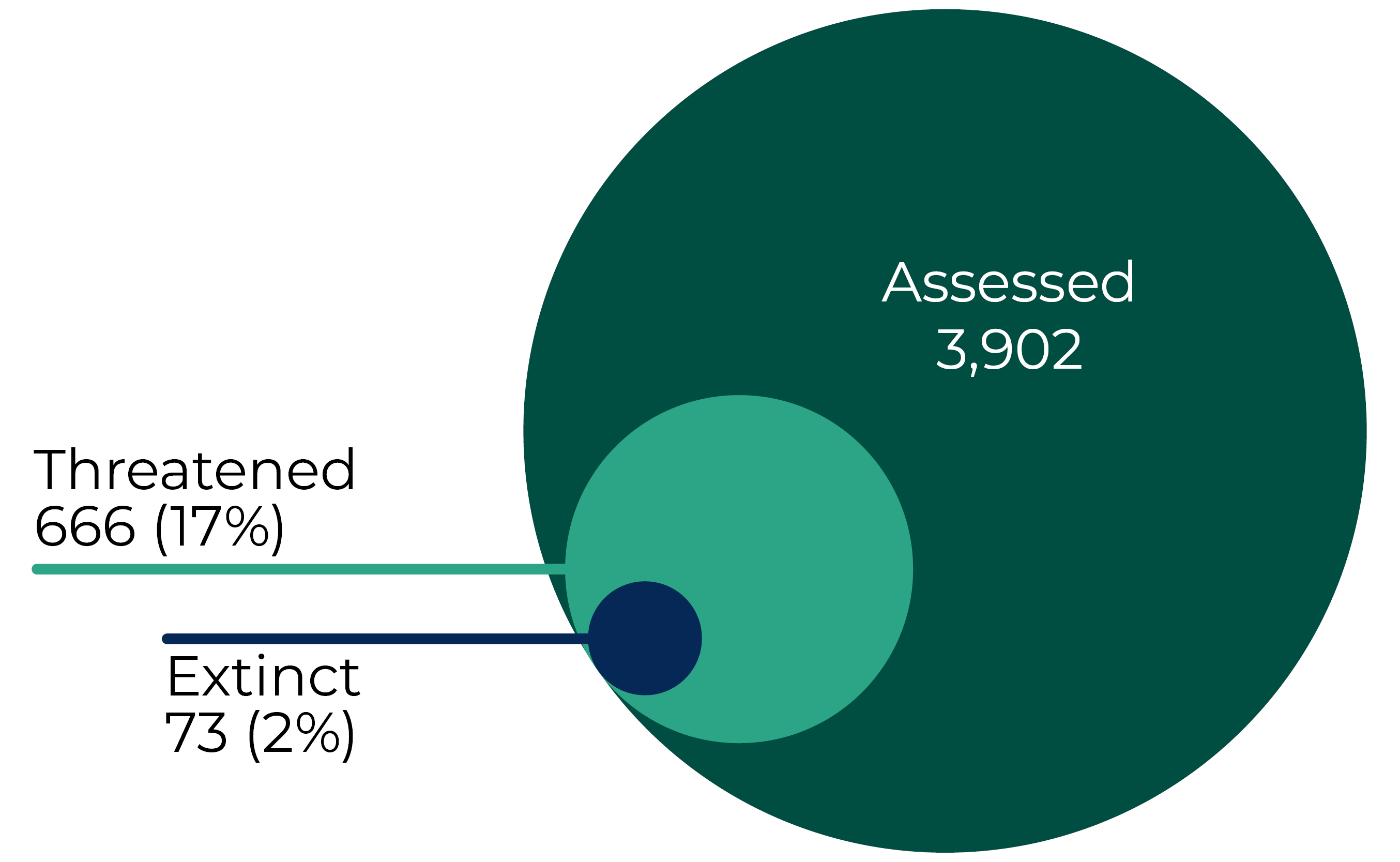

The Convention on Biodiversity treaty recently concluded that the international community failed its ten-year goal to halt the loss of nature by 2020. The environment sector’s collaborative State of Nature Report 2019 highlighted that 17% of species in Wales are threatened with extinction (see climate change article).

Species extinction risk assessment in Wales (1970 baseline)

Source: The State of Nature Report 2019

Public and political emphasis on a green recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has stimulated debate on ‘nature based solutions’ such as catchment management to reduce flooding and a national forest to tackle climate change. The future farming policy will no doubt feature in these debates.

Decisions on agricultural policy in the Sixth Senedd will not be easy. Politicians will need to consider the viability and culture of rural communities; the developing trading environment and the declared nature and climate emergencies. Evidently the future policy will have far reaching effects.

Article by Katy Orford, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament