“Wales is a country very strongly defended by high mountains, deep valleys, extensive woods, rivers, and marshes.”

It’s hard to imagine that Britain was once covered almost entirely by trees. Even in 1194, when the historian and author Gerald of Wales wrote down these travel impressions, most of the ancient wildwood had already vanished because of human needs for timber, firewood and farmland.

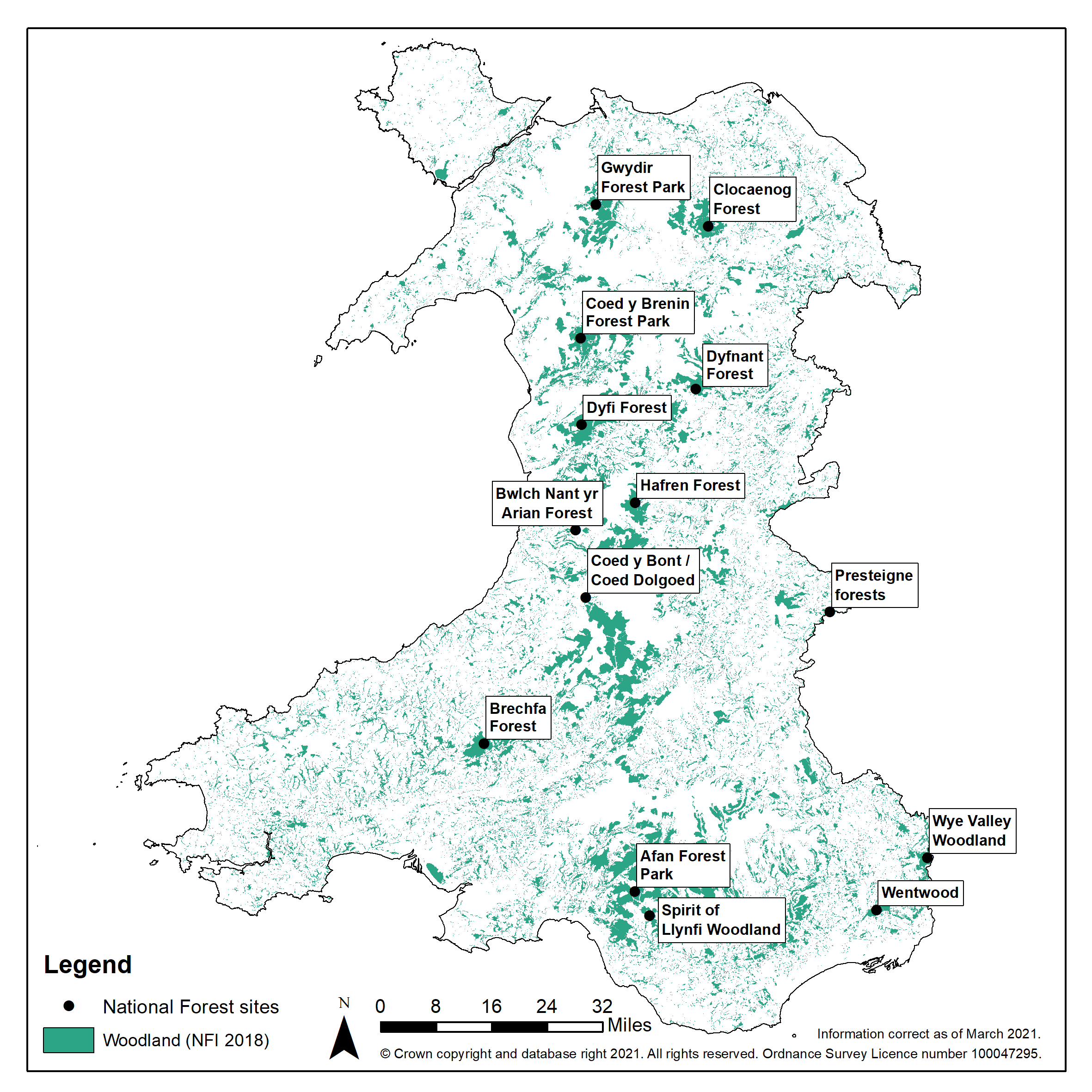

Today, only around 15% of Wales is woodland. Recent plans by the Welsh Government to create a National Forest spanning “the length and breadth of Wales” aim to restore parts of what once dominated the British landscape.

What is the National Forest?

The National Forest is to be a connected ecosystem of ancient and new woodlands. It was first put forward by the now First Minister, Mark Drakeford, in his leadership manifesto in 2018. With scope and ambition matching the Wales Coast Path, existing woodland would be improved to meet the UK’s forestry standards, but new trees would be planted, too. The Welsh Government plans to collaborate with communities, farmers, foresters, public bodies, and others. The First Minister said in 2020 that:

“Trees improve air quality, they remove harmful greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, they provide material for construction, they regenerate soil for food, they clean the water in our rivers and they provide a home to all the life that finds shelter in their canopy.”

So far, the Welsh Government has designated 14 existing woodlands as National Forest in November 2020. But a detailed picture of where the National Forest is going to be and what it will look like has not been published yet.

Woodland targets

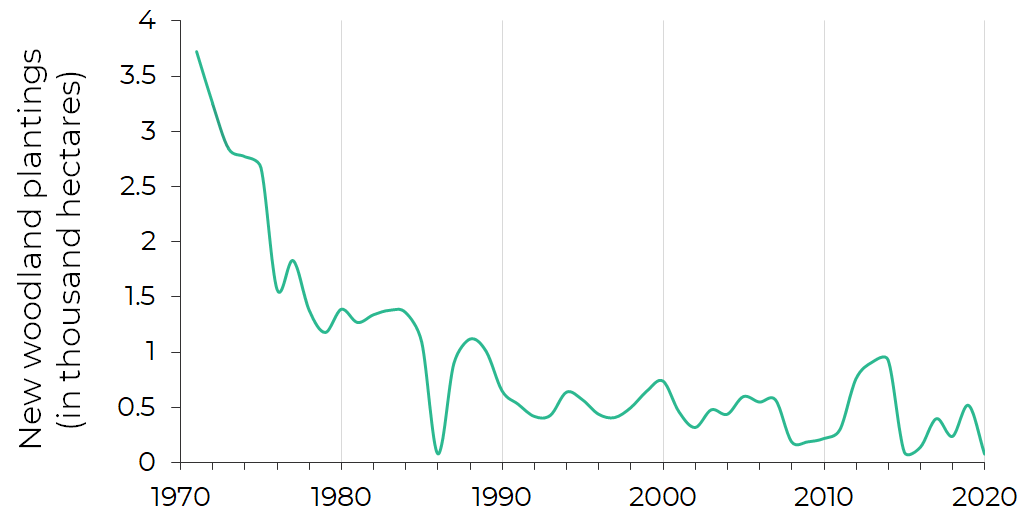

Actual levels of woodland planting continue to fall short of Welsh Government’s targets. In 2017, the Senedd’s Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee found in its report on forestry and woodland policies in Wales:

“There is a massive gap between aspiration and reality, and fundamental change in the approach to woodland creation in Wales is needed. […] The Welsh Government must lead by example and increase afforestation on public land.”

In 2018, the Welsh Government set the target for woodland planting in its Woodlands for Wales strategy to 2,000 hectares per annum. The Low carbon delivery plan (2019) reiterated this target and proposed that it be increased to 4,000 hectares per annum “as rapidly as possible”. Comparing this to recent figures (80 hectares planted in the year to 31.03.2020) shows the scope of this challenge.

Source: Forest Research, Woodland Statistics

Funding for trees

The Welsh Government allocated £5m in 2020-21 to the National Forest. Parts of that are dedicated to Community Woodlands, a capital grant scheme by the National Lottery Heritage Scheme, which provides £2.1m to community woodland projects. Further funding for woodlands is available via Glastir, the Welsh Government’s sustainable land management scheme. It provides funding to farmers and land managers for woodland creation (£17m in 2020) and restoration (£2.1m in 2020).

Benefits of a National Forest

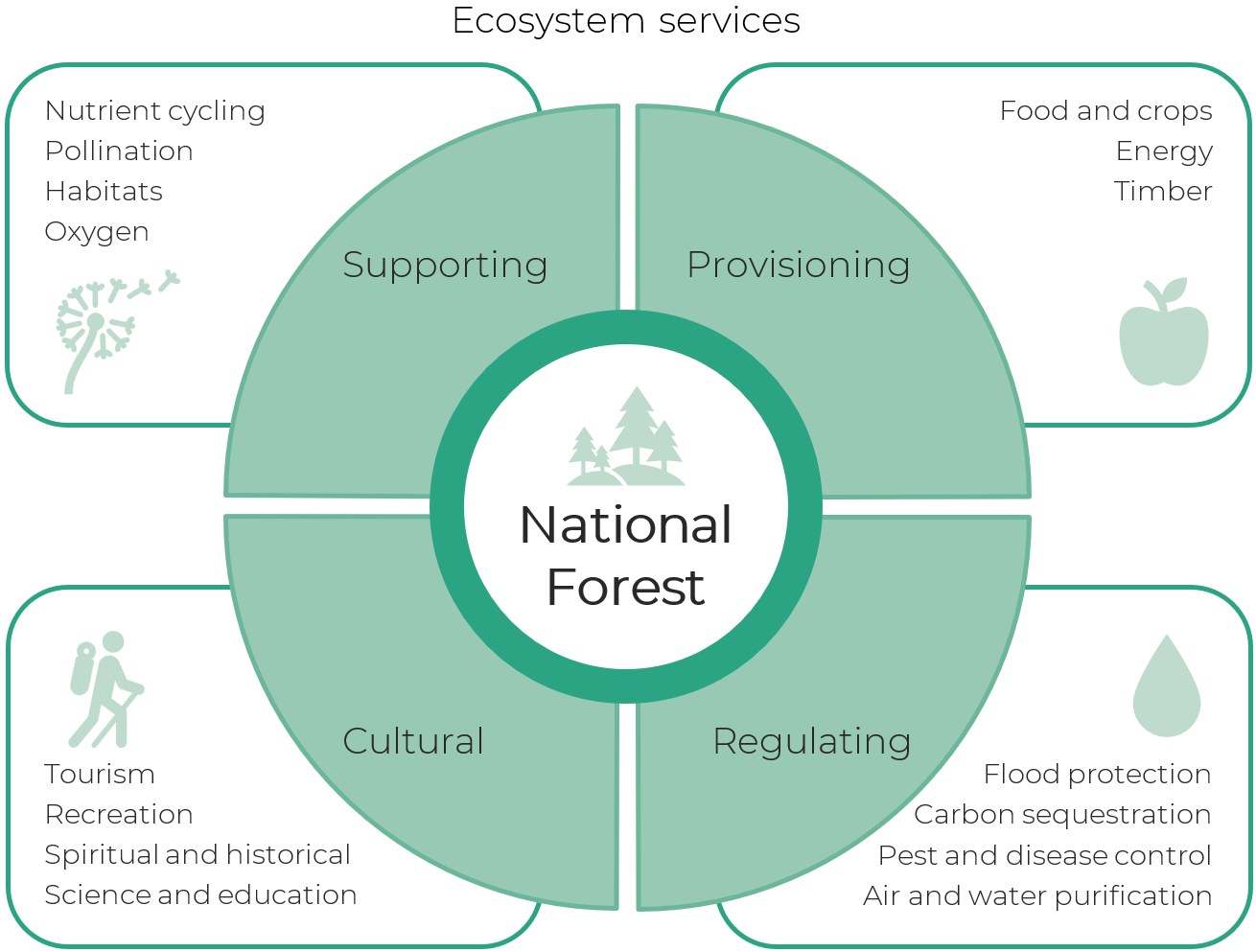

The potential benefits, or ecosystem services (PDF 339 KB), of woodlands are stated to be immense, and consequently there are many reasons for a National Forest. Woodlands are a significant carbon sink and can help address climate change. They support biodiversity and offer a rich and diverse habitat for plants and animals endangered in Wales, such as red squirrels or the Spreading Bellflower. Woodlands are a space for leisure, recreation, and exercise, and have arguably become even more important for our mental well-being during the Coronavirus pandemic. Woodlands are also an economic resource and provide timber and firewood.

Based on: Convention on Biological Diversity, Ecosystem services (PDF 339 KB)

Competing interests

Some of these interests are competing, and it might be difficult to find the right balance. The National Forest in Wales Evidence Review points out that maximising one objective would inevitably lead to trade-offs affecting the other interests. The chosen objective also determines which management approaches and tree species are adopted. The Glastir Woodland Creation scheme distinguishes between woodlands for carbon sequestration and woodlands for biodiversity.

Climate change

The UK Climate Change Committee recommends increased tree planting as a key step towards a net zero greenhouse gas emission target. As the trees grow, carbon is taken from the air and stored in the form of biomass. However, there is a crucial time lag between planting a tree and the growing phase in which it absorbs the most carbon. This needs to be considered when trying to address short-term emission targets. Woodlands created to optimise biomass production and the long-term removal ofcarbon dioxide (carbon sequestration) have a higher tree density. They use fast-growing species such as conifers, and should be harvested once they reached their age of maximum growth.

Biodiversity

Biodiversity is the variety of different species in an ecosystem. Biodiversity benefits greatly from undisturbed and deadwood habitats, and a variety of native species can in turn support further ecosystem diversity. The National Forest in Wales Evidence Review finds that benefits for biodiversity may be highest when woodland quality is improved rather than size. Biodiversity can even be lost, if woodlands are expanded into other habitats. RSPB Cymru has warned against planting trees on peatland habitats, saying this could not only disrupt rare ecosystems, but also emit stored carbon. It advocates the principle of “the right tree in the right place” – matching tree species to current and future site conditions. Woodland management should consider the changing climate and risk of wildfires and tree pests.

Forestry

Wales’ timber demand is currently mainly met by imports. The Welsh Government wants to promote the use of timber in construction to reduce carbon emissions coming from steel or concrete. There is also increasing interest in locally sourced material.

Confor, the UK’s trade association for the forestry industry, welcomes a National Forest as a game-changer for forestry and sees it stimulating rural economic growth and creating jobs. It would also enable farmers, as the significant landowners, to develop alternative revenue streams.

NFU Cymru says that farmers would be keen to plant trees on their farms, to provide clean air and facilitate carbon sequestration, if appropriate support was made available. But it is concerned about the scale of afforestation in Wales and fears that it places unequal burdens on farming and rural communities. The Farmers’ Union of Wales points out its view that agriculture is the backbone of rural areas, and that large-scale tree planting would have a devastating effect.

Recreation

Both nature conservation and economic interests can compete with tourism and recreation. Visitors require infrastructure, paths, and car parks, they need places to rest, public toilets and hospitality. At the same time, evidence suggests that visitors favour a perceived “naturalness” and may dislike commercial plantations, clearcutting, and other woodland management activities.

What’s next?

A National Forest that is well-designed, appropriately located and properly managed could bring huge benefits, as environmental organisations and other stakeholders generally agree. They will await further detail on the scope and objectives of the National Forest from the Welsh Government with interest. Eventually, the success of a National Forest will be measured against how well competing interests are balanced and targets and objectives are delivered.

Article by Matthias Noebels, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament.

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Matthias Noebels by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council which enabled this Research Article to be completed.