This is the question posed by the Senedd’s Children, Young People and Education Committee (CYPE) following its scrutiny into whether ‘radical change’ is needed to services for care experienced children. On Wednesday (12 July), Senedd Members will debate both the Committee’s findings and the Welsh Government’s response.

The Welsh Government has a Programme for Government commitment to “explore radical reform of services for looked after children”. After an update on how this pledge was being taken forward, the CYPE Committee wanted to know more.

CYPE Committee Members talked extensively to care experienced children and birth parents across Wales. As well as examining key statistics, they also heard directly from a wide range of stakeholders including practitioners and managers, academics, the relevant regulator and inspectorate. The CYPE Committee also heard from the high court judges who make the legal judgements on whether children enter the care system or not.

The CYPE Committee’s subsequent report identifies 12 policy areas where it says radical reform is needed and makes 27 recommendations “to drive urgent and much-needed change”.

Members will also discuss the Welsh Government's response to a recent Senedd Petition’s Committee report about support for care experienced parents.

One child in every hundred

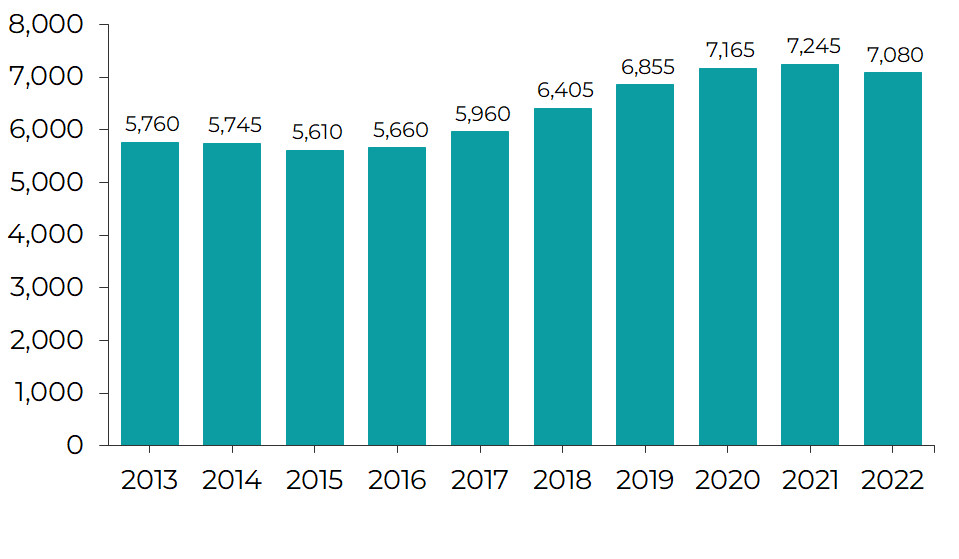

More than one child in every hundred in Wales is in care and has the ‘state’ acting as their parent. And numbers have significantly increased in the past ten years. The state is therefore responsible for where the child lives, their safety, their emotional well-being, their health, and their education. Welsh Government guidance says that “as corporate parents, each local authority must act for the children they look after as any responsible and conscientious parent would act”.

Yet the CYPE Committee’s report paints a stark picture.

Deprivation, substance misuse, parental mental health and learning disabilities are all part of a complex picture which has led to an increase in children going into the care of Welsh local authorities. Domestic abuse is a key factor in the lives of 75% of birth mothers who have had one or more children permanently removed.

There are multiple influences on the rates of children in the care of Welsh local authorities. Wales has much higher rates of children in care than England. In 2021 there were 115 per 10,000 children in the care of Welsh local authorities, compared to 67 per 10,000 in the care of local authorities in England. There are also significant unexplained variations between Welsh local authorities even when deprivation is taken into account. In 2022, Torfaen had the highest rate of 209 per 10,000 children and Carmarthenshire had the lowest rate of 45 looked after children per 10,000 population aged under 18.

Numbers of children looked after in Wales

Source: Stats Wales Children looked after at 31 March by local authority, gender and age

Does the state make a ‘good parent’?

Once children start being looked after’, the CYPE Committee found that it was commonplace for them to be moved around. A quarter had lived in two or more placements in the previous year. Fewer than one in five care experienced children achieve 5 or more A*-C grades at GCSE, including English/ Welsh and maths, compared to more than half of ‘all pupils’. Early trauma means that care experienced children may be four times as likely to have poor mental health. The report says this is an “abject failure of corporate parenting” that children don’t get the right therapeutic support, partly because the medical model of mental health services is not able to meet their very specific needs.

As children in care get older, evidence says some are placed in illegal or unregistered placements and others go missing. Some children are deprived of their liberty for welfare reasons or because there are risks to their safety. These are known as Deprivation of Liberty Orders (DoLs) and are authorised by a court. A shortage of suitable accommodation has led to concerns about an increase of ‘DoLs’ being in place for children in the care of Welsh local authorities. Speaking to the CYPE Committee, the then Family Division Liaison Judge for Wales said that these orders are used when “you are absolutely at the extreme end of trouble” and that it is “a terrible problem”.

The average age for a young person to leave their parental home in Wales is 24. Yet many children leave the care of the state at aged 18 or often sooner. The report says that the end of support from the state is like a “cliff edge” of leaving care for many young people. Leaving care was also said to be a “predictable route” into homelessness with one in four young people ending up with nowhere to live.

In what the report refers to as a “cycle of care”, the CYPE Committee says it is “appalled” that around a quarter of young people who have been in care will go on to have at least one of their own children removed by the state. The Petitions Committee found the evidence it heard on this specific issue “made for uncomfortable listening”, referring to “prejudice and pre-judgement, and harrowing tales of individuals struggling to build better lives for themselves and their loved ones.”

A “staffing crisis facing children’s social care”

Against the backdrop of a significant rise in the numbers of children in care in Wales, the CYPE Committee’s report points to children’s distress at having frequent changes of social workers. In 2022, there were 4,774 posts in children’s social work teams in Wales. The CYPE Committee was told that 639 of those posts were vacant, with half of those being vacancies for qualified social workers. It also heard that half of all children’s social care posts were covered by agency staff and 86% of those agency staff were filling vacancies for qualified social workers.

Part of the solution, according to the CYPE Committee, is for a new law to calculate maximum caseloads for children’s social workers, based on the legislative approach taken for nurse staffing levels. It says the Welsh Government should develop a new law alongside a comprehensive workforce sufficiency plan.

A personal commitment from the First Minister

Mark Drakeford has long since indicated his personal commitment to improving the care experiences of children, including a clear focus on keeping children and families together where it is safe to do so. The Programme for Government 2021-26 includes a series of commitments including:

- funding to support families whose children are at risk of going into care;

- to “eliminate private profit from the care of children looked after”;

- to increase residential services for children with complex needs closer to their homes; and

- an aim to strengthen public bodies in their role as ‘corporate parent’.

The Welsh Government also introduced a Basic income pilot for care leavers so that young people leaving care are offered £1,600 each month (before tax) for two years to support their transition to adult life.

Does the Government accept radical reform is needed?

Arguably the most significant Welsh Government Programme for Government commitment relating to care experienced children aimed to provide a clear road map for wholescale and systemic change. It was this commitment that the CYPE Committee found least evidence of. The explicit pledge is to:

“Explore radical reform of current services for children looked after and care leavers”.

It is a perceived absence of detail on this commitment which the Committee sought to address. It asks, ‘If not now, then when?’ for radical change and clearly lays down the gauntlet saying:

“Anybody claiming that the state is doing its corporate parenting job well should consider whether they would be happy for their own child to be cared for by that system.”

In May 2023, the First Minister and representatives of care experienced young people signed a joint declaration “committing to the radical reform of care services for children and young people”. Some of these young people also told the CYPE Committee about the commitments they wanted from the Welsh Government.

On 12 July, the Senedd will debate both the CYPE Committee's and the Petitions Committee’s findings. The Welsh Government has fully accepted five of the CYPE Committee’s 27 recommendations, accepting 15 in part and rejecting seven.

The Children, Young People and Education Committee has already clearly set out its verdict that there is a strong case for radical reforms and what Welsh Government must do to “drive urgent and much-needed change”.

Article by Sian Thomas, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament