Some people are more likely to suffer worse health than others.

In ‘Health inequalities: “We have a moral duty to reduce them”, Cancer Research UK reports that over 30,000 extra cases of cancer in the UK each year can be attributed to socio and financial deprivation, and survival is worse for the most deprived groups.

The British Heart Foundation Cymru also reports that “people in more deprived areas are more likely to shoulder the greatest burden of disability and death from heart and circulatory diseases”. It says the premature death rate for these conditions is 116.4 per 100,000 in Blaenau Gwent (one of the most deprived areas in Wales), compared to 58.2 in the Vale of Glamorgan (one of the least deprived areas).

This isn’t just about inequalities in access to healthcare. Most inequalities in health present before people get sick – known as the ‘social determinants of health’.

In this article we consider why this is and how Health Impact Assessments (HIA) can be used as a tool in tackling health inequalities, drawing on newly published research by the Welsh Health Impact Assessment Support Unit (WHIASU) and World Health Organisation (WHO) Collaborating Unit in Public Health Wales.

Health inequalities are profoundly unfair but they’re also avoidable

Health inequalities existed before the pandemic; but it has brought health inequalities to the fore. The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on more deprived groups, children and young people, disabled people, people from ethnic minority backgrounds and women.

Professor Sir Michael Marmot, a leading figure on health inequalities, published the Marmot Review in 2010 on the differences in health and wellbeing between social groups in England. It described how the social gradient on health inequalities (i.e. avoidable inequalities in health between groups of people) is reflected in the social gradient on educational attainment, employment, income, quality of neighbourhood and so on.

In addressing health inequalities, Marmot says the social determinants of health – the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age - must be addressed.

Just at the start of the pandemic (February 2020), Marmot published a second report, looking back on the Marmot Review, 10 years on. Unfortunately, the results weren’t positive; health inequalities have got worse.

In fact, Wales’ Chief Medical Officer, Sir Dr Frank Atherton, used his first annual report in 2016 to focus on health inequalities. We published an article then, highlighting how the gap between those with the best and worst health and wellbeing was widening.

The cost of living crisis is only going to widen this inequality, given the connection between ‘health and wealth’.

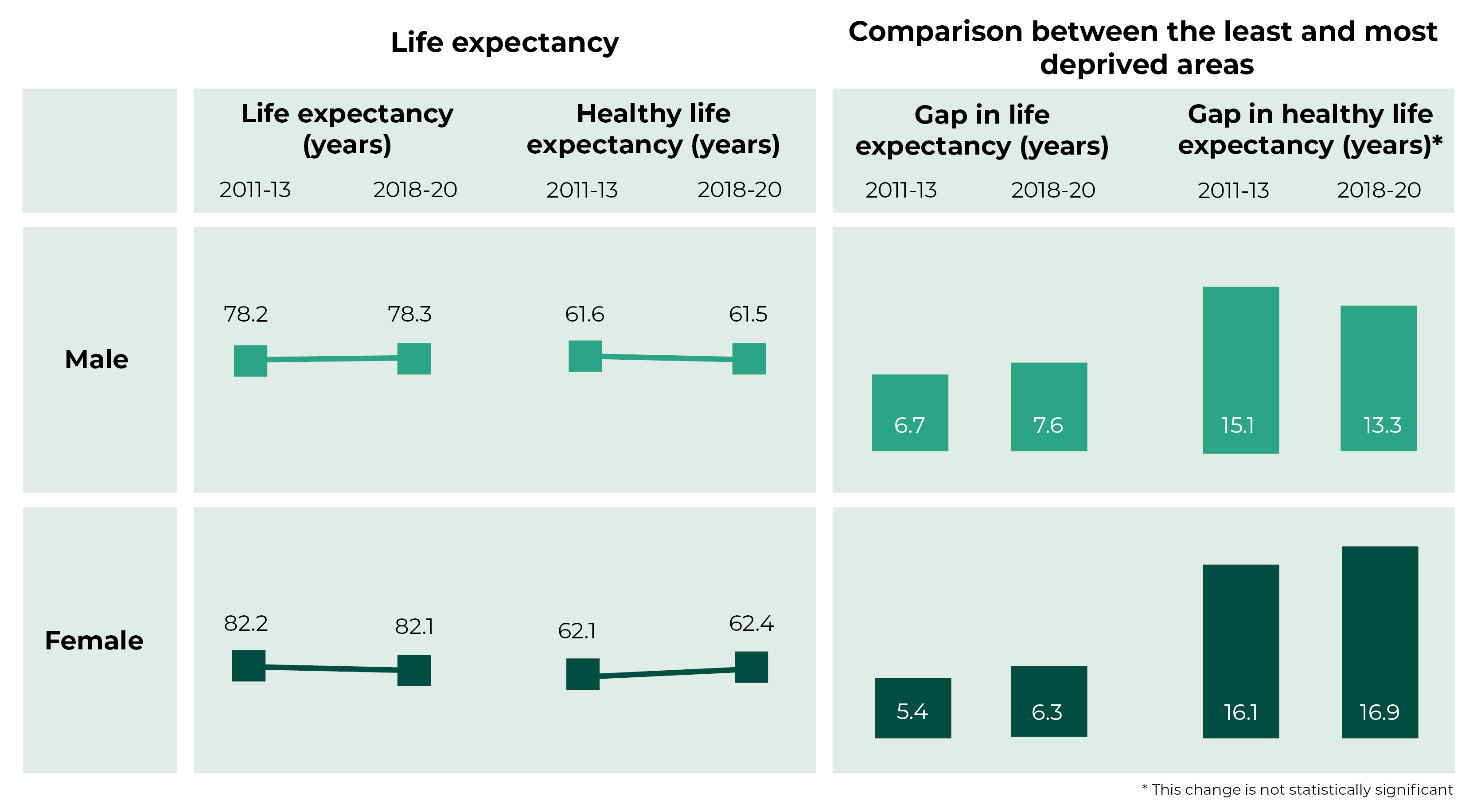

Source: Public Health Wales, Health expectancies in Wales with inequality gap (report and methodology)

Health Impact Assessments are used to better understand the health and equity impacts of policy decisions

The WHO defines a HIA as a practical approach used to judge the potential health effects of a policy, programme or project on a population, particularly on vulnerable or disadvantaged groups. It involves analysing a policy with a health lens.

The WHO say HIAs can help “decision-makers make choices about alternatives and improvements to prevent disease or injury and to actively promote health”.

The Public Health (Wales) Act 2017 received Royal Assent in July 2017. It requires HIAs to be carried out by public bodies in specific circumstances (as yet undefined). Statutory Regulations were anticipated to be published in 2020/21. But almost five years later, the Welsh Government is yet to issue them.

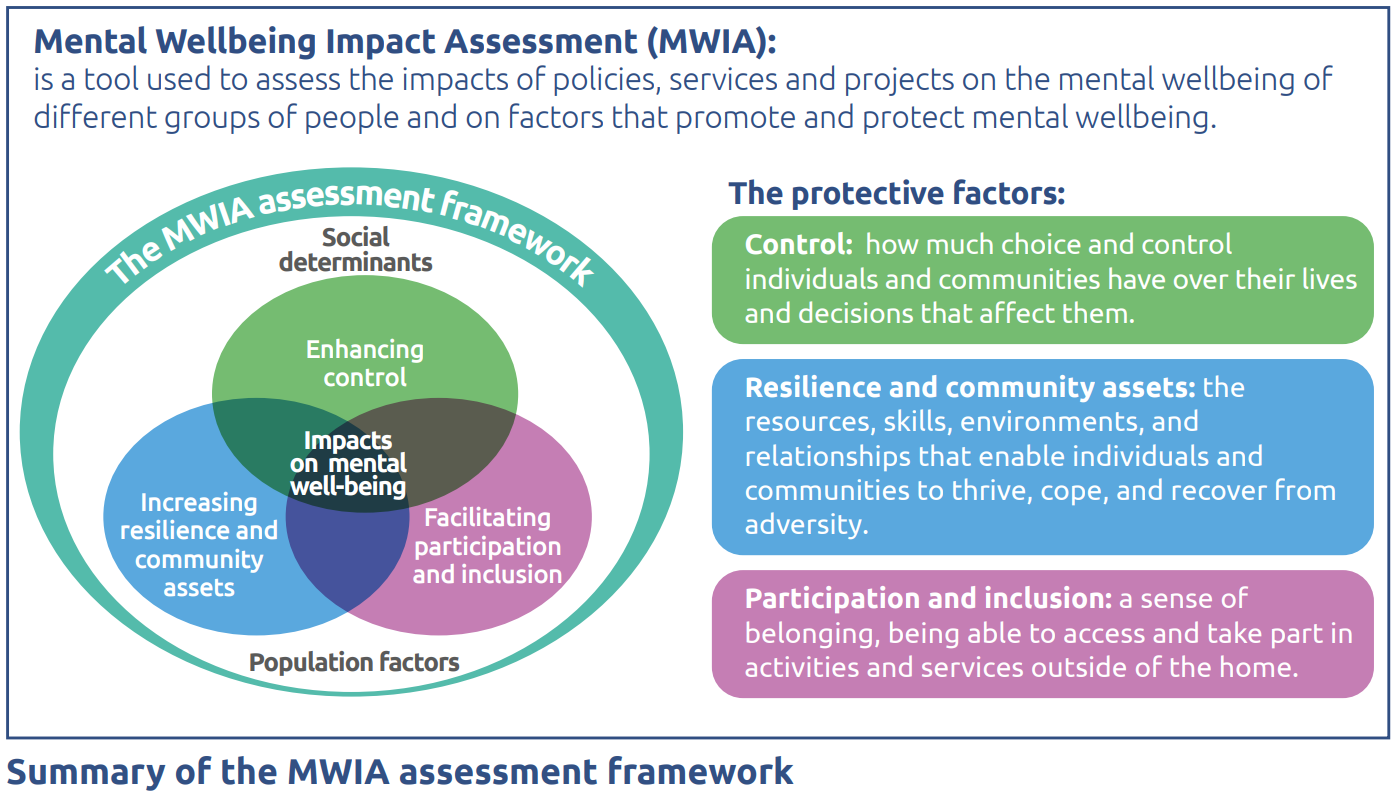

Public Health Wales has published the results of its Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment (MWIA), looking specifically at the impact of the pandemic on young people aged 10-24 years. The MWIA is a specific assessment which is built on HIA methods.

The report states that “the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted every young person in Wales, some more negatively than others”. School closures, lockdowns, social distancing and self-isolation requirements are noted.

The MWIA identifies 18 population groups that have been adversely affected, including:

- young adults aged 16-24, particularly young women

- young people living in low-income families

- young people with additional learning needs

- young people with mental health problems.

It also refers to the creation of new vulnerabilities for some groups such as young people advised to shield and those with parents as key workers.

Main report findings – who is most affected and how?

The MWIA attempts to provide an evidence-based picture of the nature of the impacts and who’s most affected in the population. It also identifies areas where further research is needed to fully understand ongoing impacts.

The report considers the social determinants of mental wellbeing:

- economic insecurity;

- educational access and outcomes;

- good quality housing with space to study;

- access to private or local outdoor space; and

- internet connectivity and access to digital devices.

And the protective factors for mental wellbeing:

- enhancing control;

- increasing resilience and community assets;

- facilitating participation and inclusion.

The impact on people’s health must be considered across all policy areas

The MWIA is an interesting read; it demonstrates how learning from COVID-19 pandemic impacts on mental wellbeing is important - not only for future pandemic planning, but also for the climate emergency and longer term population mental health.

The report identifies longer term impacts on wellbeing that need to be considered to address future health inequalities. It highlights the inextricable links between health, wellbeing and other policy areas.

The Welsh NHS Confederation’s Health and Wellbeing Alliance brings together professionals from across Wales. In April 2021, thirty-six health and care organisations endorsed a joint paper calling on the Welsh Government to show “national leadership on ending inequalities”.

It pressed the Welsh Government to respond with urgency stating that “for too long, we have looked at the health service to address these challenges in isolation”. It added:

The NHS alone simply doesn’t have the levers to make the changes we know are vital to creating the conditions necessary for good health. Meaningful progress will require coherent efforts across all sectors to close the gap.

The joint paper says that “sustained, focused and coordinated action across all government departments is required to tackle the root causes of health inequalities”.

The Alliance has called for a cross government strategy for tackling poverty and inequalities that sets out existing commitments, provides some clarity around shared outcomes and provides transparency in how performance will be measured. It also recommends Senedd Committees work together to undertake full parliamentary scrutiny.

The Alliance will be publishing a further report ‘Mind the gap: what’s stopping change? The cost-of-living crisis and the rise in inequalities in Wales’ at the end of this week.

Article by Sarah Hatherley Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament