Summer is well underway and Natural Resources Wales (NRW) is visiting bathing waters around Wales measuring their water quality. You may see this water quality information and classifications displayed at bathing sites – but what do the results mean, and how clean are bathing waters in Wales?

What is a bathing water?

Bathing waters are recreationally and economically important for Wales, and contribute heavily to coastal tourism. They are identified using guidance from The Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017 (‘WFD 2017’), which was transposed from the 2000 EU Water Framework Directive (‘EU WFD’).

They are designated by the Welsh Government if there are large numbers of bathers throughout the bathing season, which lasts from 15 May to 30 September each year. The Welsh Government also considers any infrastructure or facilities provided, or other measures taken to promote bathing at the site, when making designation decisions. The 109 designated bathing sites in Wales are predominately coastal, only one (Llyn Padarn in Llanberis) is inland.

The list of bathing waters is reviewed annually, and anyone can apply to get a bathing water designated.

Bathing waters are protected by law

The WFD 2017 sets a framework for managing ecological, chemical and physical aspects of environmental water quality – discussed further in our research briefing: ‘Water Quality in Wales’. However, bathing sites are a special class of protected waters and are subject to additional monitoring and quality standards.

These standards are found in the Bathing Water Regulations 2013 (BWR), which transpose identification, monitoring and water quality improvement practices from the EU Bathing Water Directive 2006 (BWD) into UK law. The BWD aims to:

…preserve, protect and improve the quality of the environment, and protect human health.

The BWR outline criteria for assessing bathing water status. Bathing water status is additional to the chemical and ecological statuses assessed for surface waters under the EU WFD, and can be ‘excellent’, ‘good’, ‘sufficient’, or ‘poor’. Local authorities must signpost the bathing water status next to bathing waters, along with any appropriate advice for bathers.

Implementation and compliance with bathing water standards is overseen by NRW. Bathing water quality is also promoted by voluntary schemes like the Blue Flag award programme. Beaches can qualify for ‘blue flag’ status if they have ‘excellent’ water quality, and meet additional requirements around facilities, education and beach cleanliness.

Bathing water classification depends on bacteria levels

NRW monitors the bathing waters across Wales, by carrying out testing throughout the bathing season. NRW says it will test each bathing water at least 10 times over the 2023 season.

Bathing waters are monitored for two types of bacteria; Escherichia coli (E.coli) and intestinal enterococci. These species are targeted as they indicate faecal matter is present, which can make bathers ill.

Bacterial contamination data from the past four years is then used to classify bathing waters against the BWR’s standards. Poor waters don’t comply with the standards and contain unacceptable levels of bacteria, whilst sufficient, good and excellent classifications have their own threshold criteria. The results are published by NRW in its annual bathing water quality report (information is also available in an interactive map).

Bathing water quality has increased over recent years

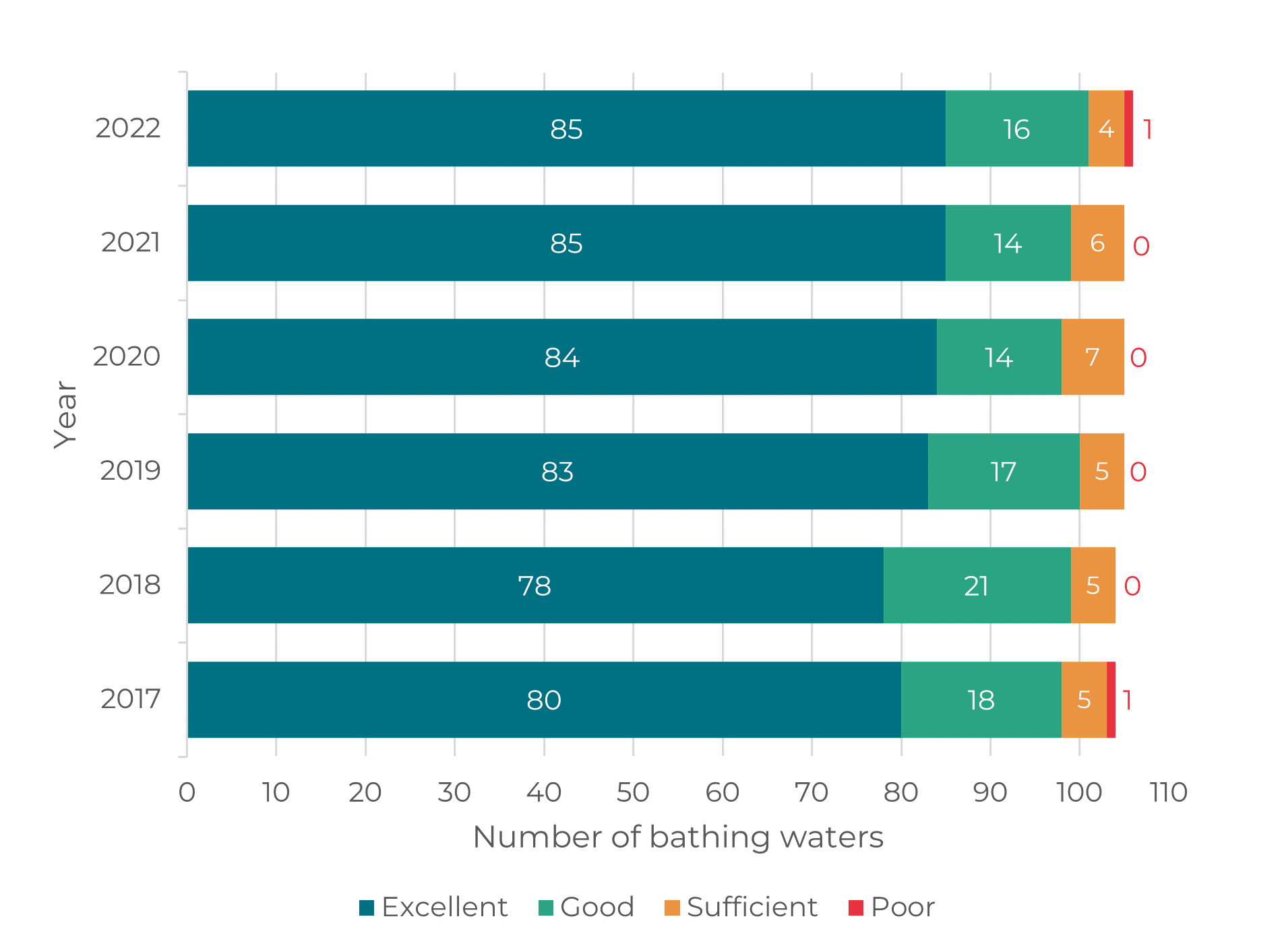

The bar chart below summarises NRW’s annual Wales bathing water quality report data from 2017-2022, showing the number of bathing water sites for each classification.

Number of Welsh bathing waters by classification, 2017-2022

Source: NRW Wales bathing water quality reports (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022).

The percentage of bathing waters classified as ‘excellent’ rose from 76.9% to 80.2% between 2017-2022. NRW reported that in 2022, 105 of 106 designated bathing waters met the minimum water quality standards, representing 99% compliance with the BWR.

Marine Lake, Rhyl, was classified as ‘poor’ in 2022, and is the only non-compliant bathing water assessed since 2017. NRW attributed the Marine Lake’s bacterial contamination to recent draining and refilling of the lake, combined with heavy rainfall necessitating sewer discharge into the lake before sample collections.

Wales’ bathing water quality is higher than the UK average

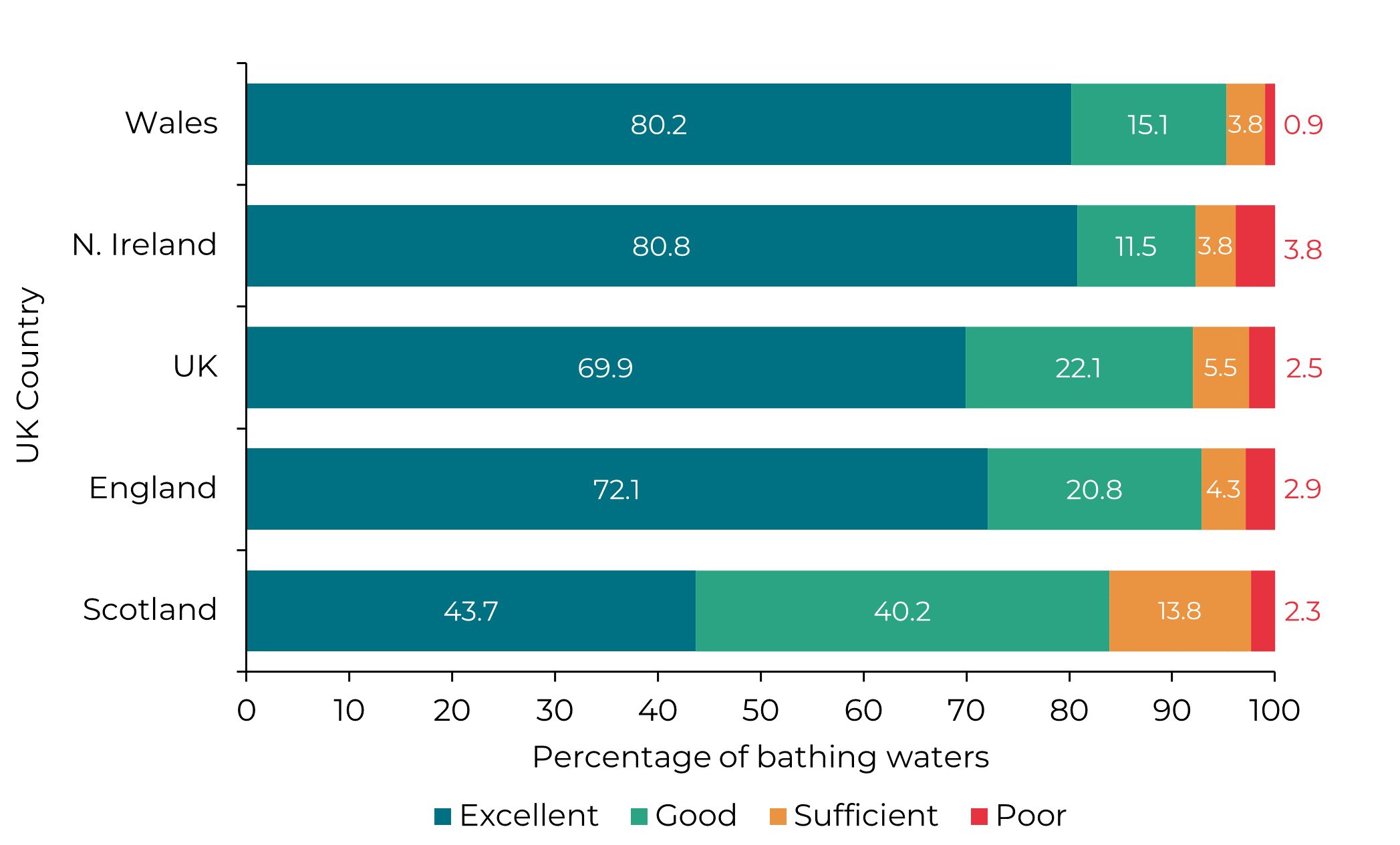

In 2022, 92.3% of Welsh bathing waters were classified as ‘good’ or better, the highest figure of all UK nations. At 80.2%, Wales’ percentage of ‘excellent’ bathing waters also exceeded the UK average.

Proportion of bathing waters across UK countries, by 2022 classification (%)

Source: NRW bathing water quality report 2022, SEPA bathing water data, DEFRA 2022 bathing water statistics, DAERA 2022 bathing water data.

However, Wales and the UK still lag behind other countries implementing BWD standards. In 2022, the overall percentage of ‘excellent’ bathing waters in the EU was 85.7%.

Sewage is a major source of bathing water pollution in Wales

NRW says the top five sources of bathing water pollution are:

- water industry sewage discharges;

- water draining and carrying pollution from agricultural land;

- dog, bird and other animal faeces on or near beaches;

- water draining and carrying pollution from urban areas; and

- domestic sewage pollution due to misconnected drains and septic tanks.

‘Combined storm overflows’ (CSOs) can cause ecological damage and bacterial pollution, but are allowed at bathing sites and associated waters. The water industry’s use of CSOs to discharge sewage into the environment often makes headlines. CSOs are sometimes necessary during heavy rainfall to prevent flooding elsewhere in sewerage systems, and are regulated through discharge permits issued by NRW.

According to data compiled by ‘Top of the Poops’, in 2022 Dŵr Cymru discharged sewage into designated bathing sites for an estimated 36,500 hours. This was the second highest figure among water companies in England and Wales.

In May 2023, Dŵr Cymru published plans to support Welsh bathing water quality. This includes providing more detailed and up to date alerts on sewage spills at bathing waters, and investing £560m between 2020-2030 to improve storm overflows.

Wales has excellent coastal bathing waters – but what next?

Freshwater recreation is popular in Wales, with 26% of respondents to a 2022 Welsh Government survey saying they had participated in water activities at rivers, lakes or reservoirs in the past few years. However, almost all Welsh bathing waters are coastal.

According to Surfers Against Sewage (SAS), the lack of inland bathing sites where bacteria levels are monitored is concerning. SAS suggest over 90% of sewage discharges in England and Wales go into rivers, it estimates that three out of four rivers pose a risk to human health.

The Welsh Government’s 2021-26 Programme for Government has committed to strengthen inland water quality monitoring, by beginning “to designate Wales’ inland waters for recreation”.

Research commissioned by the Welsh Government suggests such a move is favoured by nearly two-thirds of respondents. The Welsh Government’s bathing water reviews in 2022 and 2023 also restated its commitment to this measure. However, Wales’ only inland bathing water for the 2023 bathing season remains the freshwater Llyn Padarn in Gwynedd, which was designated in 2014. For now, it’s unclear when we’ll find out if our rivers are as safe for swimming as our seas.

Article by Olivia Watts, PhD intern, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Olivia Watts by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council which enabled this article to be completed.