Article by Robin Wilkinson, National Assembly for Wales Research Service

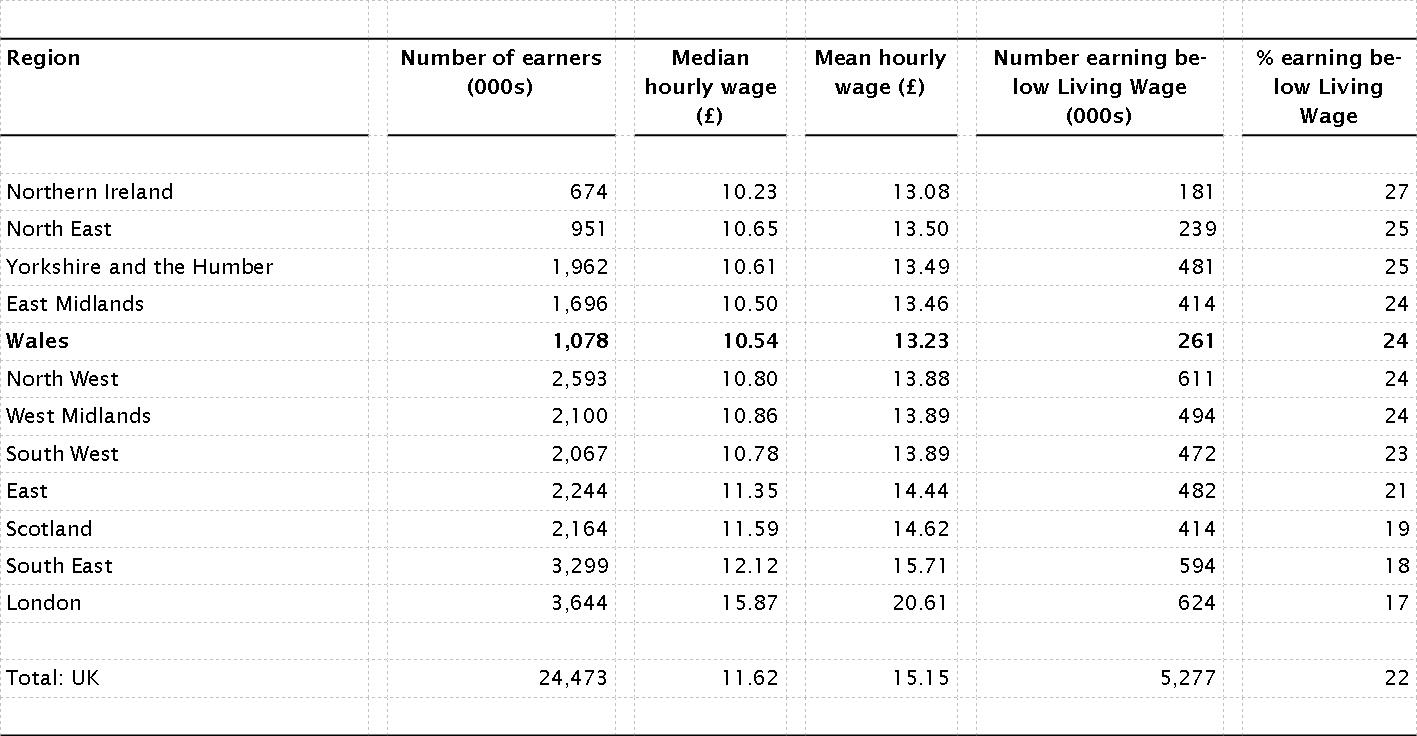

This week, as part of Living Wage Week, the Living Wage Foundation announced that the Living Wage for 2014-15 is £7.85. This is an increase of 2.6 per cent from last year’s figure of £7.65. Supporters argue that the voluntary Living Wage is a key weapon in the fight against rising in-work poverty, both in Wales and the UK. The Living Wage, calculated by academics at Loughborough University, is intended to reflect the amount of money an individual needs to earn to live a decent life. As opposed to the National Minimum Wage, it is a voluntary measure that employers choose to adopt, rather than enforceable by law (more information is available in a Research Paper published by the Research Service, The Living Wage: Questions and Answers, though this document does not reflect the new rate or most recent statistics). As the table below shows, a study has found that Wales is the region in the UK with the fifth largest proportion of workers receiving less than the Living Wage, at 24 per-cent of those in employment (Northern Ireland had the largest, at 27 per-cent). This is 1 per-cent lower than last year’s figure of 25 per cent.  Source: KPMG, Living Wage Research Report, using estimates produced by Markit Economics Limited, November 2014 Figures published by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2013 showed that Wales has more working-age adults and children in low-income working families (285,000 on average in the three years to 2010/11) than in low-income non-working ones (275,000). Being paid a Living Wage would clearly help low-paid workers. It is, however, worth noting that in recent years the Living Wage has been set lower than the actual amount felt to be necessary to meet minimum living costs. This is so as to avoid a large increase to the Living Wage whilst wage increases in general fall behind rapidly-rising living costs. As well as the benefit to individuals and their families, advocates suggest that paying the Living Wage could save the Treasury over £2 billion a year (the result of higher income tax payments and national insurance contributions and lower spending on benefits and tax credits, minus increased costs of paying public sector workers currently paid less than the Living Wage). Added to the fact that Living Wage policies are said to benefit employers – from happier, healthier and more productive employees to corporate reputational benefits – and the Living Wage starts to look like a silver bullet to many modern problems. Indeed, in June the Living Wage Commission, chaired by the Archbishop of York Dr John Sentamu, published a report that called on the UK Government to increase the uptake of the Living Wage to benefit at least 1 million more employees by 2020. Recommendations aimed at devolved governments included paying public sector workers the Living Wage and using procurement to encourage businesses to pay staff the Living Wage. Though Dr Sentamu has called the Living Wage “the litmus test of a fair recovery”, the report falls short of recommending the introduction of a compulsory Living Wage. It warns that the increased wage bill would not be affordable for some firms in some sectors, such as retail and hospitality, and for many small firms. Some quarters, however, have responded cautiously to the Living Wage debate. The UK Government has stated that making employers raise wages above the level of the National Minimum Wage would have an adverse effect on employment: something that should be borne in mind when advocates consider the extent to which employers should be coerced by the state into paying the Living Wage. Others, though, have argued that that the benefits to the economy of widespread adoption of the Living Wage could actually increase employment levels. Business representatives have also argued that nudging businesses to pay above the Minimum Wage would result in a less competitive economy, and that though many businesses would love to pay their staff more, this is precluded by the current weak economic situation. Either way, as David Cameron said before becoming Prime Minister, the Living Wage is “an idea whose time has come”. Its relevance to Wales is illustrated by the high levels of low-income working families and employees currently paid less than the Living Wage. The Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee has recently begun an inquiry into poverty in Wales, which will look at issues including in-work poverty and the role of the Living Wage in the new year. Whether the Living Wage is a socioeconomic cure that should be actively supported by politicians, or remain purely a matter for the discretion of individual employers is a subject for debate both in Wales and Westminster, and one that will no doubt feature heavily in the Committee’s work, as well as the build-up to the 2015 and 2016 elections.

Source: KPMG, Living Wage Research Report, using estimates produced by Markit Economics Limited, November 2014 Figures published by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2013 showed that Wales has more working-age adults and children in low-income working families (285,000 on average in the three years to 2010/11) than in low-income non-working ones (275,000). Being paid a Living Wage would clearly help low-paid workers. It is, however, worth noting that in recent years the Living Wage has been set lower than the actual amount felt to be necessary to meet minimum living costs. This is so as to avoid a large increase to the Living Wage whilst wage increases in general fall behind rapidly-rising living costs. As well as the benefit to individuals and their families, advocates suggest that paying the Living Wage could save the Treasury over £2 billion a year (the result of higher income tax payments and national insurance contributions and lower spending on benefits and tax credits, minus increased costs of paying public sector workers currently paid less than the Living Wage). Added to the fact that Living Wage policies are said to benefit employers – from happier, healthier and more productive employees to corporate reputational benefits – and the Living Wage starts to look like a silver bullet to many modern problems. Indeed, in June the Living Wage Commission, chaired by the Archbishop of York Dr John Sentamu, published a report that called on the UK Government to increase the uptake of the Living Wage to benefit at least 1 million more employees by 2020. Recommendations aimed at devolved governments included paying public sector workers the Living Wage and using procurement to encourage businesses to pay staff the Living Wage. Though Dr Sentamu has called the Living Wage “the litmus test of a fair recovery”, the report falls short of recommending the introduction of a compulsory Living Wage. It warns that the increased wage bill would not be affordable for some firms in some sectors, such as retail and hospitality, and for many small firms. Some quarters, however, have responded cautiously to the Living Wage debate. The UK Government has stated that making employers raise wages above the level of the National Minimum Wage would have an adverse effect on employment: something that should be borne in mind when advocates consider the extent to which employers should be coerced by the state into paying the Living Wage. Others, though, have argued that that the benefits to the economy of widespread adoption of the Living Wage could actually increase employment levels. Business representatives have also argued that nudging businesses to pay above the Minimum Wage would result in a less competitive economy, and that though many businesses would love to pay their staff more, this is precluded by the current weak economic situation. Either way, as David Cameron said before becoming Prime Minister, the Living Wage is “an idea whose time has come”. Its relevance to Wales is illustrated by the high levels of low-income working families and employees currently paid less than the Living Wage. The Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee has recently begun an inquiry into poverty in Wales, which will look at issues including in-work poverty and the role of the Living Wage in the new year. Whether the Living Wage is a socioeconomic cure that should be actively supported by politicians, or remain purely a matter for the discretion of individual employers is a subject for debate both in Wales and Westminster, and one that will no doubt feature heavily in the Committee’s work, as well as the build-up to the 2015 and 2016 elections.