This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

Skills are critical to making Wales a more prosperous nation. But raising qualification levels in the population is not enough. There are other challenges that must be overcome, such as stimulating employer demand for higher level skills.

Skills are a key factor in improving productivity and pay, both of which drive economic growth and higher living standards.

Since 2008, qualification levels among the working age population in Wales have risen substantially

Yet, Wales - like the UK - is in the midst of an entrenched productivity problem, with parts of the nation trapped in “a cycle of low-skill, low-wage and low-productivity”.

‘Sluggish’ productivity alongside increasing qualification levels shows that any relationship between skills and prosperity is not a simple one.

Some of the challenges that will face the new Welsh Government include the need to consider employer demand for skills, getting the content of qualifications right, and the take-up and provision of lifelong learning.

Qualification levels may outstrip employer demand for them

The supply of qualifications into the labour market is likely to carry on growing, but demand for high level skills from employers may not keep pace.

One study projects that:

The supply of highly qualified people will grow more quickly than demand for such qualifications.

This is already happening in Wales where qualifications levels between 2004 and 2018 rose fastest in the lowest skilled occupations, with the over-qualification rate hovering at around 40% in the decade to 2017.

There is also considerable debate over the impact of automation and technology on certain jobs. New occupations could be created and current ones made redundant or considerably changed. But some experts urge caution against:

[assuming] the introduction of new technologies will automatically raise the demand for more skilled workers, increase productivity or reduce income inequality in Wales

Employers aren’t always interested in highly skilled workers

Many enterprises are profitable without a highly-skilled workforce. This means many workers in Wales work in a ‘low-skills equilibrium’ where low demand for high level skills from employers mean there is little requirement or incentivisation for workers to gain higher level skills.

While these firms can be profitable, low-skills equilibriums are associated with poorer personal outcomes and lower pay for their workers.

However, just increasing the supply of highly skilled workers is not enough, it can just mean employers do not fully utilise those skills. The OECD explains that:

having skills is not enough; to achieve growth, both for a country but also for an individual, skills must be put to productive use at work

The policy implication is that the supply of skills into the labour market, and employer demand for higher level skills, must be considered at the same time.

Mismatches between skill supply and skill demand have negative consequences

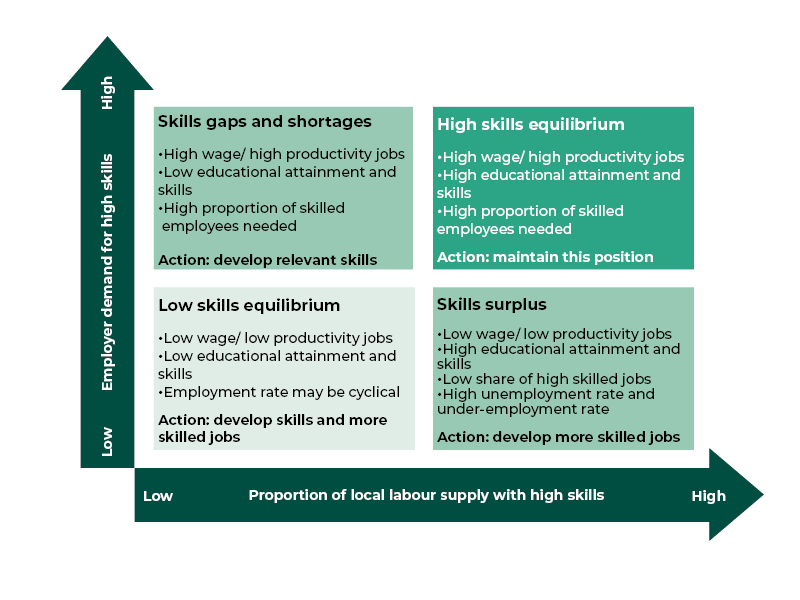

Low-skills equilibriums are just one outcome from the interaction between skill supply and skill demand.

Outcomes from interactions between skills supply and employer demand

Source: adapted from Future of Skills & Lifelong Learning and Low skill traps in sectors and geographies.

Mismatched supply and demand can result in skills shortages and skills surpluses. While some level of skills mismatching is normal in a dynamic economy, it can:

slow the adoption of new technologies, cause delays in production, increase labour turnover and reduce productivity.

There are three approaches to trying to align skills with demand:

- Learner preference: where providers adjust their curriculums to match the demand of learners. This is arguably the model operated in the UK higher education sector.

- Central planning: where a central or regional body gathers data and labour market intelligence to forecast employer skills demand so skills provision can be centrally planned. This is the basis of the Regional Skills Partnership model used in Wales.

- Market determination: where learners are free to choose their programmes, but the programmes on offer are driven by employer demand, like the apprenticeship programme.

The Employer Skills Survey sets out an understanding of skill mismatches in Wales.

Education participation falls with age, and part-time learning numbers continue to fall

A UK Government Office for Science report contends that:

Collectively [changes to employment patterns] point to lifelong learning as the pathway for skills-driven economic growth, building on the skills that individuals have when they leave the education system, and enabling workers to adapt to changing demands for skills.

But the data paints a challenging picture.

In general, participation in education and skills training falls significantly with age with the overall number of learners in further and higher education, and work-based learning falling substantially from aged 40 onwards.

In 2019, over three-quarters of 16-18 year olds were in education or training. This falls to just over a third of 19-24 year olds (largely made-up of higher education students) and drops further among 25-30 year olds to just over 10%.

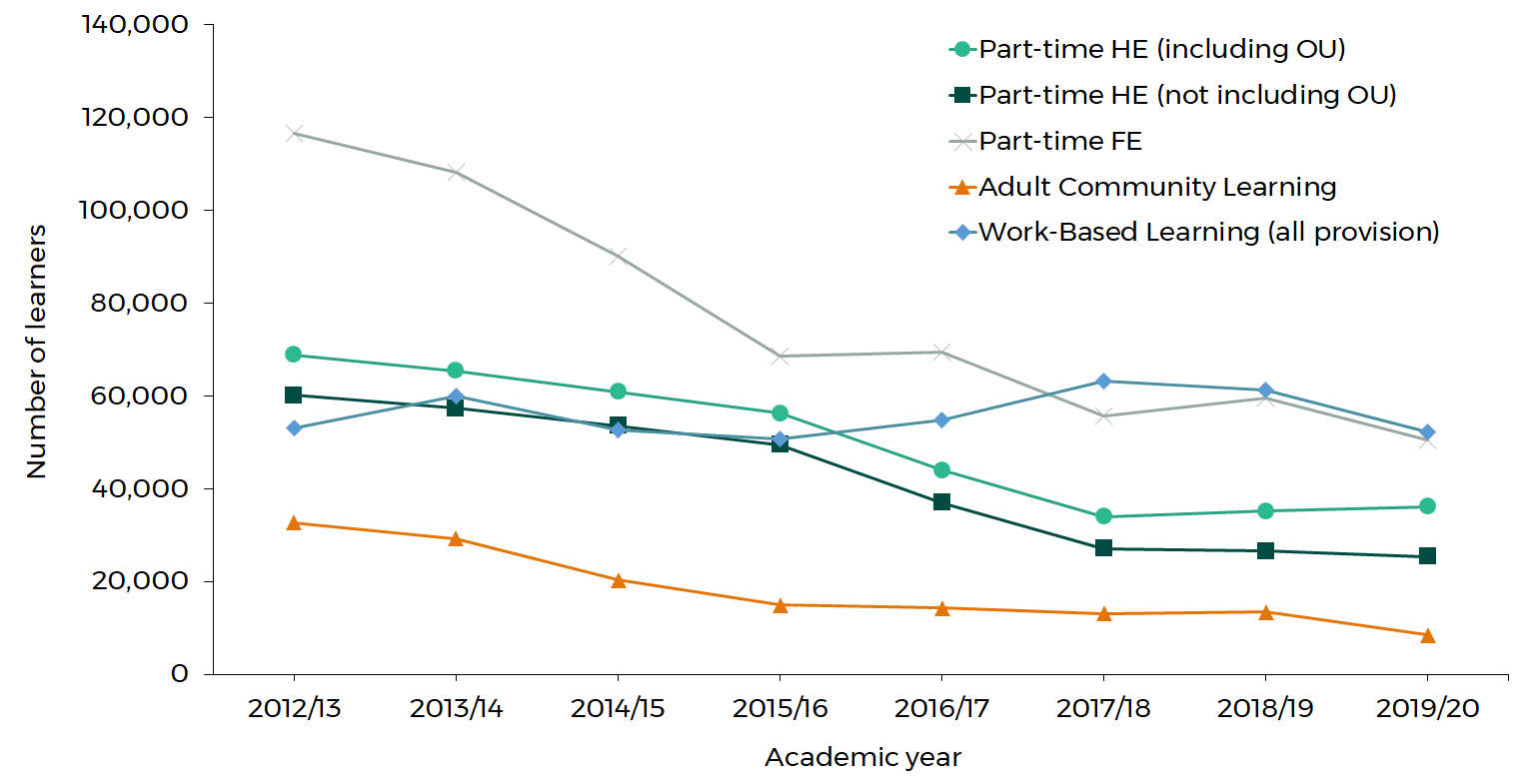

At the same time, there has been a significant trend of falling part-time learning in higher and further education, and adult-community education.

While recent reforms to part-time higher education student support appear to have stimulated an increase in higher education part-time learning, further analysis shows that this increase has been driven by The Open University. This suggests that the fall in part-time learning in higher education at least, presents a complex problem for policymakers, which goes beyond just the financial support available.

Trend in part-time learners in Wales

Source: StatsWales

Employers are a key source of lifelong learning. Yet while the proportion of Welsh workers receiving training in the workplace has increased, the intensity of training has fallen. On top of this, the picture is not an even one, with one analysis showing that:

Women, younger people, those with higher qualifications, occupants of higher skilled jobs and those who work in the public sector are the strongest beneficiaries [of work-place training].

Some argue current skills qualifications do not prepare learners for change

An ongoing debate in skills policy is what attributes courses should develop in learners.

Should skills provision focus on preparing learners for specific job-related tasks, or be a broader offering, with more emphasis on general education and ‘soft skills’ that employers are known to value?

Arguing against what it sees as the status quo, a Colegau Cymru commissioned report contends that there is too little general education in UK vocational qualifications:

Unlike school and university, much of Further Education is concerned with immediately relevant competencies. […] In place of competencies it is important vocational education builds on the broader notion of capability – giving all citizens capacity to adapt rapidly to changing circumstances.

The challenges ahead

Skills are one key road to making Wales more prosperous. But while qualification levels in Wales have risen, the new Welsh Government will face other deeper challenges if it is to ensure the skills system fulfils its potential to improve the prosperity of Wales.

Article by Phil Boshier, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament