Since the first antibiotic was discovered nearly 100 years ago, antimicrobial drugs have become a staple of modern healthcare. They’re used to treat infectious diseases but overuse is driving antimicrobial resistance (AMR), making some infections untreatable. As a result, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has classed AMR as one of the top 10 global health problems threatening humanity. In this article, we look at what the Welsh Government is doing to tackle this problem so antimicrobials can continue to be used to save lives in the future.

The threat of antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobials are used to treat diseases caused by infectious agents, like bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites. There are different types of antimicrobials which are used to treat different infections. For example, antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Antivirals are another type of antimicrobial, used to treat herpes and HIV.

But over time these bugs (bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites) can evolve characteristics that make antimicrobial drugs ineffective against them. This process is called antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

AMR is driven by the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials. For example, taking antibiotics, which are used against bacterial infections, to treat a viral infection (such as a cold or the flu, or viral gastroenteritis) can create the perfect conditions for resistant bacteria to thrive.

Some bugs develop resistance against several antimicrobials. These multi-drug resistant infections, or ‘superbugs’ as they’re more commonly known, are often untreatable. These infections, which include MRSA and C. diff, are often acquired in healthcare settings.

The WHO has warned that if we don’t get AMR under control then common medical procedures which rely on the use of antimicrobials, including chemotherapy and surgery, may also become highly risky in the future.

According to the most recent estimates, 1.3 million people around the world die each year from a bacterial AMR infection. These figures don’t include deaths as a result of other infectious agents, such as viruses or fungi, meaning the overall burden of AMR is likely even higher.

The number of deaths from AMR infections is expected to rise, with a report commissioned by the UK Government in 2016 forecasting that AMR infections will be responsible for 10 million deaths worldwide per year by 2050.

More recently, scientists have found that warming global temperatures caused by climate change can drive further development of AMR. As a result, they suggested that the projection made in the UK Government report could be underestimating the future scale of the problem.

Fighting antimicrobial resistance

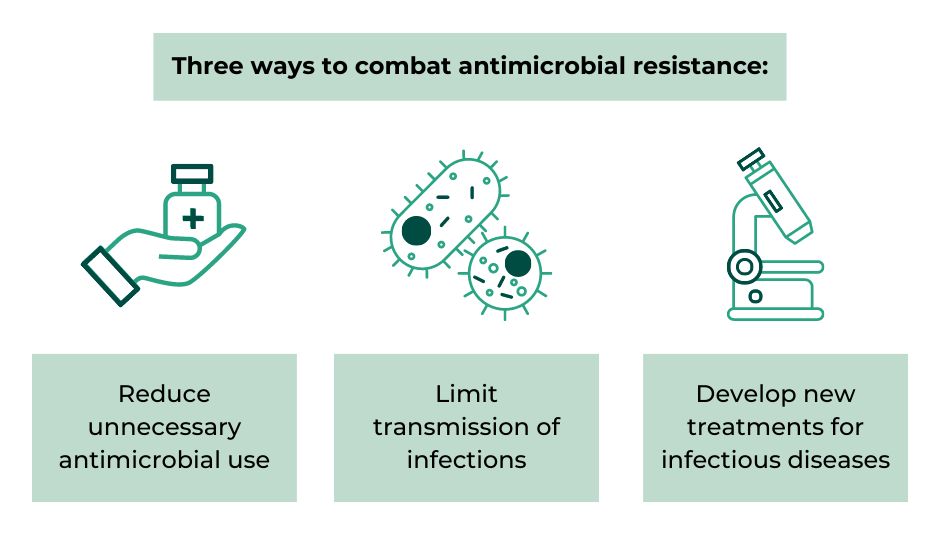

There are three main ways to fight AMR: by reducing the number of antimicrobials we use, limiting the transmission of infections so that antimicrobials aren’t needed as often and developing new antimicrobials.

Source: UK 20-year vision for antimicrobial resistance. UK Government.

Scientists around the world, including at Cardiff University and Swansea University, are trying to create new treatments which could offer alternate options for treating infections. However, progress has been slow. This means for now, the main strategies available to fight AMR are by reducing the use of antimicrobials and limiting the spread of infections.

Reducing the use of antimicrobials

Antimicrobials are often not necessary to treat common infections, such as a cold or the flu, as the immune system can fight many of these bugs without help. This means these drugs should be reserved for the most serious infections or for people who are immunosuppressed.

In the UK, over 70% of antimicrobials are prescribed in primary care, yet 20% of these prescriptions are estimated to be unnecessary. As a result, there’s a large focus on reducing prescriptions in primary care as a means of tackling AMR.

NHS Wales has produced Primary Care Antimicrobial Guidelines which provide advice to clinicians to ensure antimicrobial prescribing is only used where necessary.

Limiting the spread of infections

There’s also a drive to reduce infections, especially healthcare-associated infections, to tackle AMR. In Wales, there’s a standardised manual on Infection Prevention & Control protocols used to support reduced infection transmission risk in healthcare settings.

Getting AMR under control

The UK-wide 20-year vision for antimicrobial resistance was developed in 2019 by the UK Government and the devolved administrations, in line with the WHO Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance.

The four nations have committed to bringing AMR under control in the UK by 2040 using the three main strategies mentioned above. This will be implemented via four five-year National Action Plans (NAP), the first of which covers 2019 – 2024. This aims to:

- reduce antimicrobial use in humans by 15% by 2024; and

- reduce specific drug-resistant infections in people by 10% by 2025.

The Chief Medical Officer for Wales provides guidance and improvement goals to NHS Wales each year to support implementation of the UK-wide NAP. The latest circular was due to be published by 31 March 2023, but this is yet to be released.

Public Health Wales set up the Healthcare Associated Infection & Antimicrobial Resistance Programme (HARP) in 2017 to monitor AMR and healthcare-associated infections.

However, publicly available data on progress towards tackling AMR in Wales is limited. AMR data was last published in Scotland and England in November 2022 but the latest available data for Wales is from 2019.

The latest published data on the prevalence of healthcare-associated infections shows there was an increase in rates of several healthcare-associated infections in 2021/22, including a 24% increase in C. diff and a 13% rise in E. coli.

Public Health Wales has created an online system called ‘Antibiotic Eye’ to improve monitoring of antimicrobial use in primary and secondary care. However, the information in the system can only be accessed by NHS Wales staff meaning it can’t be used for general scrutiny of progress towards tackling AMR.

Specific action on antibiotic prescribing

The Welsh Government has published a set of National Prescribing Indicators to support safe and optimised prescribing of various medications, including antimicrobials. It set a target for NHS Wales to reduce prescribing of antibiotics, which are specifically used to treat bacterial infections, by at least 5% in primary care (compared to the baseline quarter, ending December 2019).

The latest figures show that antibiotic prescribing has gone in the opposite direction from that intended. From September to December 2022, prescription rates of these drugs in Wales had increased by 15% compared with the baseline.

However, the National Prescribing Indicators report suggests this could be due to the rise in Streptococcus infections (Strep A infection in children) which occurred over winter 2022. Prior to this, rates of antibacterial prescribing had been gradually decreasing.

Despite the recent reversal in progress, the new target for 2023 – 2024 is more ambitious than the previous one. Health boards should aim to achieve a 10% reduction in antibiotic prescriptions against the baseline period of April 2019 – March 2020.

Article by Ailish McCafferty, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Ailish McCafferty by the Medical Research Council which enabled this research article to be completed.