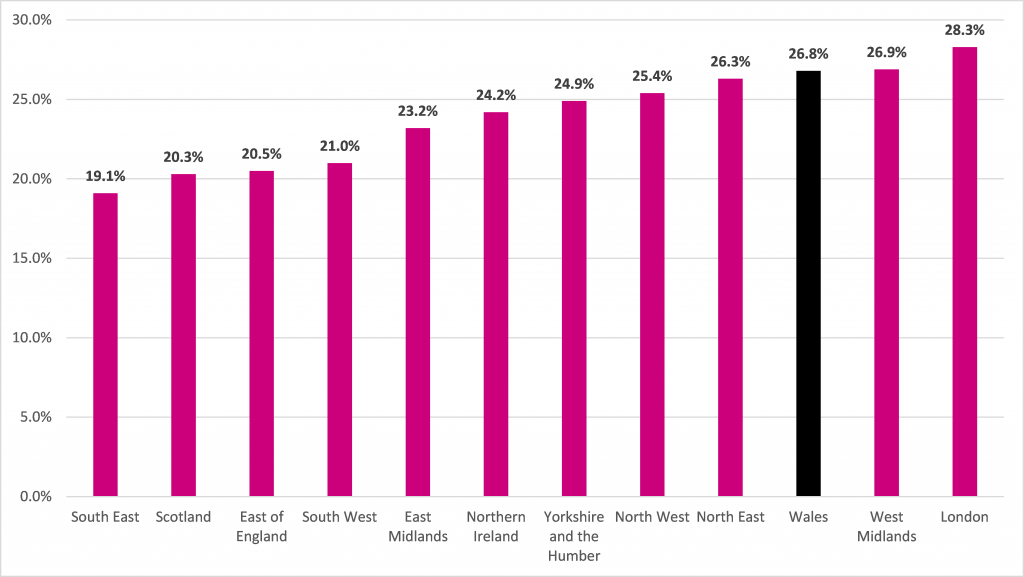

More than one in five people in Wales (23% of the population) currently live in poverty, which is the highest level of all UK nations. This means that 710,000 people in Wales live below the poverty line, including 185,000 children, 405,000 working-age adults and 120,000 pensioners.

Forecasts of poverty in Wales predict that the situation is not set to improve. By 2021-22, it is estimated that 27% of the Welsh population will be living in poverty, and that 39% of children will live in poverty.

The Welsh population living in poverty is expected to increase 3 percentage points (pp) by 2021-22. This is the third highest increase of all UK regions, behind only Northern Ireland and the North East with a projected 4pp increases respectively. The level of child poverty in Wales is projected to increase 10pp by 2021-22, higher than all areas except the North East, where child poverty is anticipated to increase by 12pp.

Figure 1: Estimated percentage of the population in poverty, 2019-20 to 2021-22  Figure 2: Estimated percentage of children in poverty, 2019-20 to 2021-22

Figure 2: Estimated percentage of children in poverty, 2019-20 to 2021-22

How poverty is measured

Poverty is measured in various ways, but the standard measurement of poverty used by the UK Government is ‘relative low income’, or ‘relative poverty’. A household is in relative poverty if its income is below 60% of the median household income, after housing costs. This includes all income, both from employment and benefits, and is measured after tax. So, for a couple with no children, the poverty ‘line’ would be £248 a week, £144 a week for a single person and £401 a week for a couple with two children.

However, income-based measures of poverty have been widely criticised, including by government ministers, for a number of reasons, which are explored below.

What and who the standard poverty measure excludes

Relative poverty excludes multidimensional (meaning that they are based on a range of factors, rather than just one), disaggregate (meaning that they are broken down to different groups of people) and individual (meaning that it takes account of personal experience) measures of poverty and deprivation because it measures incomes at a household level rather than at an individual level.

Deprivation indicators (such as the Wales Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD), which is used to determine eligibility for programmes like Flying Start) are multidimensional, but they are not comparable between countries. So factors closely associated with poverty such as poor mental health, risk of crime, housing problems and poor physical health do not feature strongly in the standard picture of poverty.

Relative poverty also excludes individuals living in households living only slightly above the poverty threshold. This is particularly significant with the rise of in-work poverty across the UK. Research funded by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) estimates that the proportion of people in ‘absolute poverty’ (which is when household income is measured against 60% median income level in 2010, rather than 60% contemporary median) would have been 0.5 percentage points higher in 2013-14 if the threshold was based on inflation rates that vary with household income.

Official poverty statistics also exclude a range of people living in institutions, such as nursing homes, halls of residence, barracks or prisons, and homeless people living rough or in bed and breakfast accommodation.

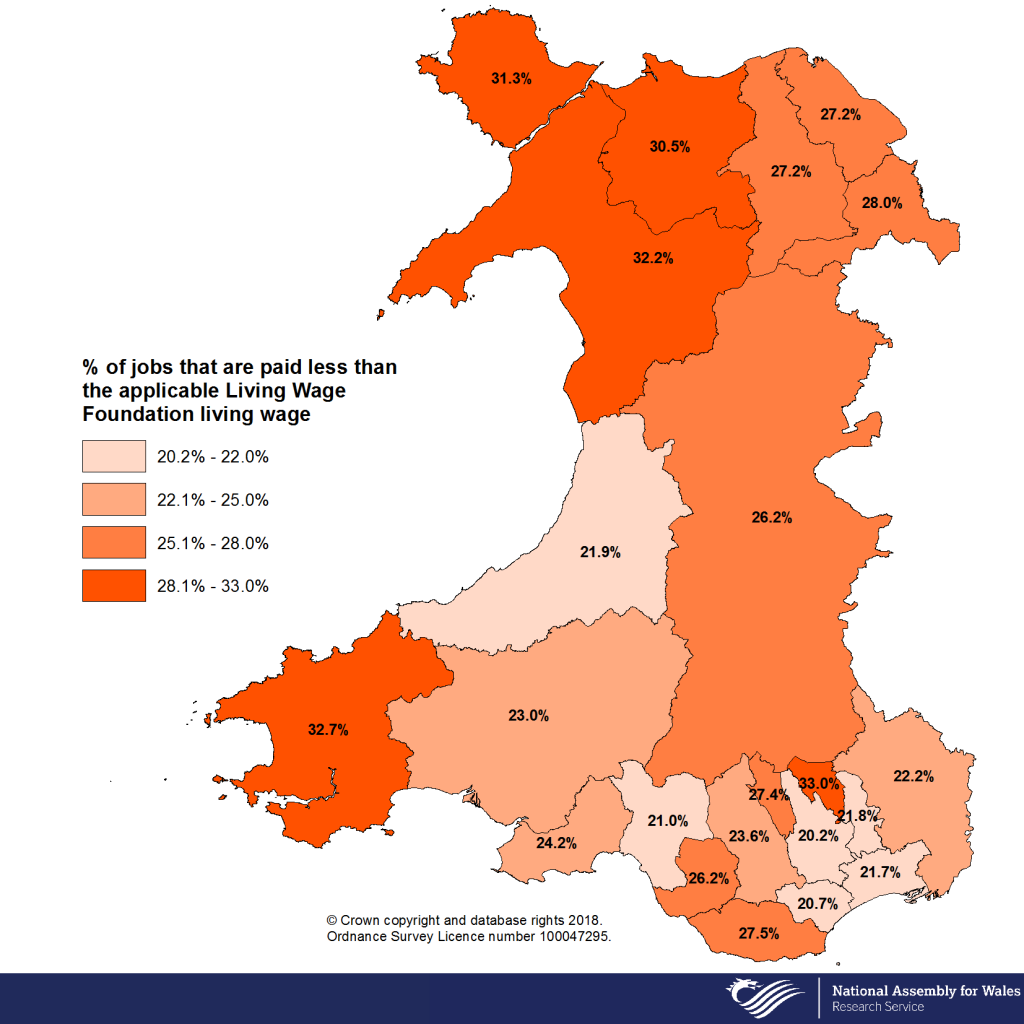

The multidimensional nature of deprivation measurement means fewer people are excluded from the measures. However, regional variations reveal the extent of low-paid work in rural areas, and some industrial areas in the South Wales Valleys. In five Welsh local authorities – Blaenau Gwent, Pembrokeshire, Gwynedd, Anglesey and Conwy - more than 30% of workers are paid less than the voluntary Living Wage. At the other end of the spectrum, around 20% of workers in Caerphilly, Cardiff and Neath Port Talbot are paid less than the voluntary Living Wage. Indeed, research has found that rural areas are at a higher risk of deprivation if access to services are included as a measure of poverty.

Finally, despite adding a multidimensional element, deprivation data typically excludes deprived individuals living in affluent areas.

Individual experience

Qualitative research has shed light on some of the complexity surrounding the poverty experience and on barriers to moving and staying out of poverty. A Welsh Government funded study of children’s experience of poverty, for example, shows school experiences to be shaped by background and geographical location. Children from poorer backgrounds show acceptance of their social position at an early age including a low level of expectation for the educational qualifications they will achieve relative to better off children.

Other studies of perceptions of poverty consolidate the complexity of the poverty experience beyond income including forms of stigmatisation, normalisation and indication of ‘poverty’ perceived by those labelled ‘poor’ by national indications, which go beyond the material.

A better way to understand poverty?

Recent research shows that multidimensional measurements of material and non-material deprivation can add value to existing income-based poverty measures. Mixed methods to capture the complexity and multifaceted nature of experiencing poverty are also of value, because they can shed light on deeper barriers to exiting ‘poverty’ based on culture, norms and self-perception.

Policies such as wraparound childcare services are designed to overcome this issue, but benefits and associated support, such as Free School Meals, continue to be allocated based largely on income (as well as savings and housing costs).

Our previous blog post on new ways of thinking about poverty highlighted other ways of targeting anti-poverty programmes, using geographic, demographic or universal approaches.

Consultation responses to the recent National Assembly for Wales Inquiry into Poverty in Wales revealed concern around the various dimensions of poverty echoed here. The former Communities, Equality and Local Government Committee recommended in 2015 that the Welsh Government “adopts a clear definition of poverty”, which is based on “the measurement of whether a person's resources are sufficient to meet their minimum human needs, and to have an acceptable living standard which allows them to participate in society”.

Article by Dr Sioned Pearce, Wales Institute of Social & Economic Research, Data & Methods (WISERD), Hannah Johnson and Gareth Thomas, National Assembly for Wales Research Service

Figure 1 Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2017-18 to 2021-22

Figure 2 Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2017-18 to 2021-22