This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

Before the pandemic almost a quarter of people in Wales lived in poverty. The past year has hit the poorest the hardest, so how can the next Welsh Government address this?

Tackling poverty has been a perennial challenge for successive Welsh Governments, and will continue to be with the pandemic having exacerbated existing inequalities. The Fifth Senedd’s Equality, Local Government and Communities (ELGC) Committee concluded that during the pandemic poverty has been a key factor in determining how likely people are to lose their jobs or income, fall behind in their education, and even how likely they are to die from COVID-19..

The Institute for Fiscal Studies warned that the slowdown in the economy will “undoubtedly have a large negative impact on household incomes over the coming years” as workers lose their jobs, and earnings fall.

|

What is poverty? A person is considered to be in poverty if their household income falls below 60% of the UK median (which is the middle value in a list of numbers that have been arranged from smallest to largest). The median weekly household income in the UK is £476 after housing costs, and 60% of this is around £286. |

Poverty trends before the pandemic

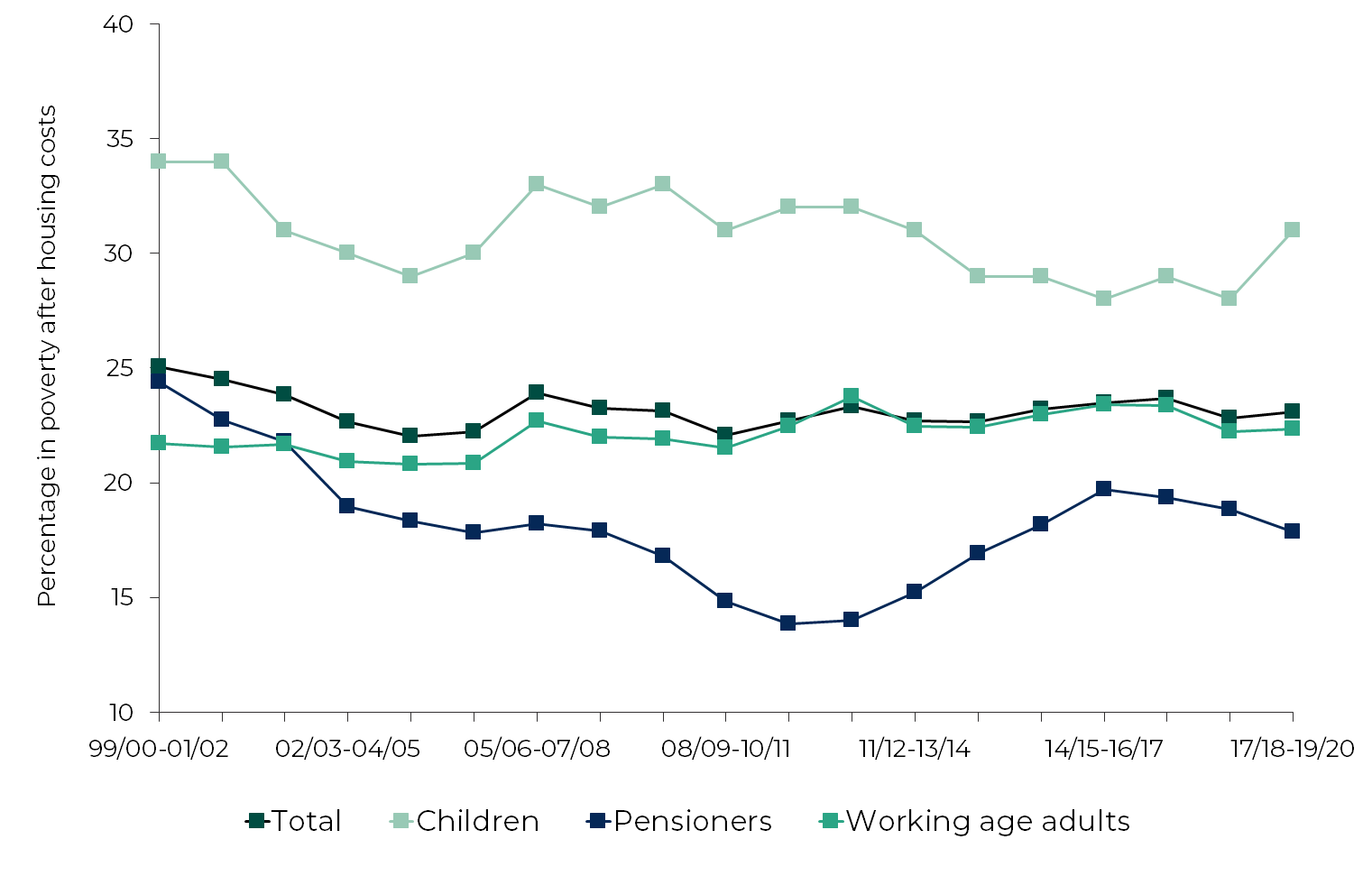

Poverty has remained stubbornly high over recent years, with Wales having the highest poverty rate of the UK nations prior to the pandemic. Children are more likely than other age groups to be in poverty, with 31% living in poverty – the only age group to see an increase in the latest figures Chwarae Teg noted that women and single parents are also more likely to be in poverty.

Percentage in poverty after housing costs in Wales, 1999/2000 – 2001/2002 to 2017/2018 – 2019-2020

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, Households below average income: 1994/95 to 2019/20

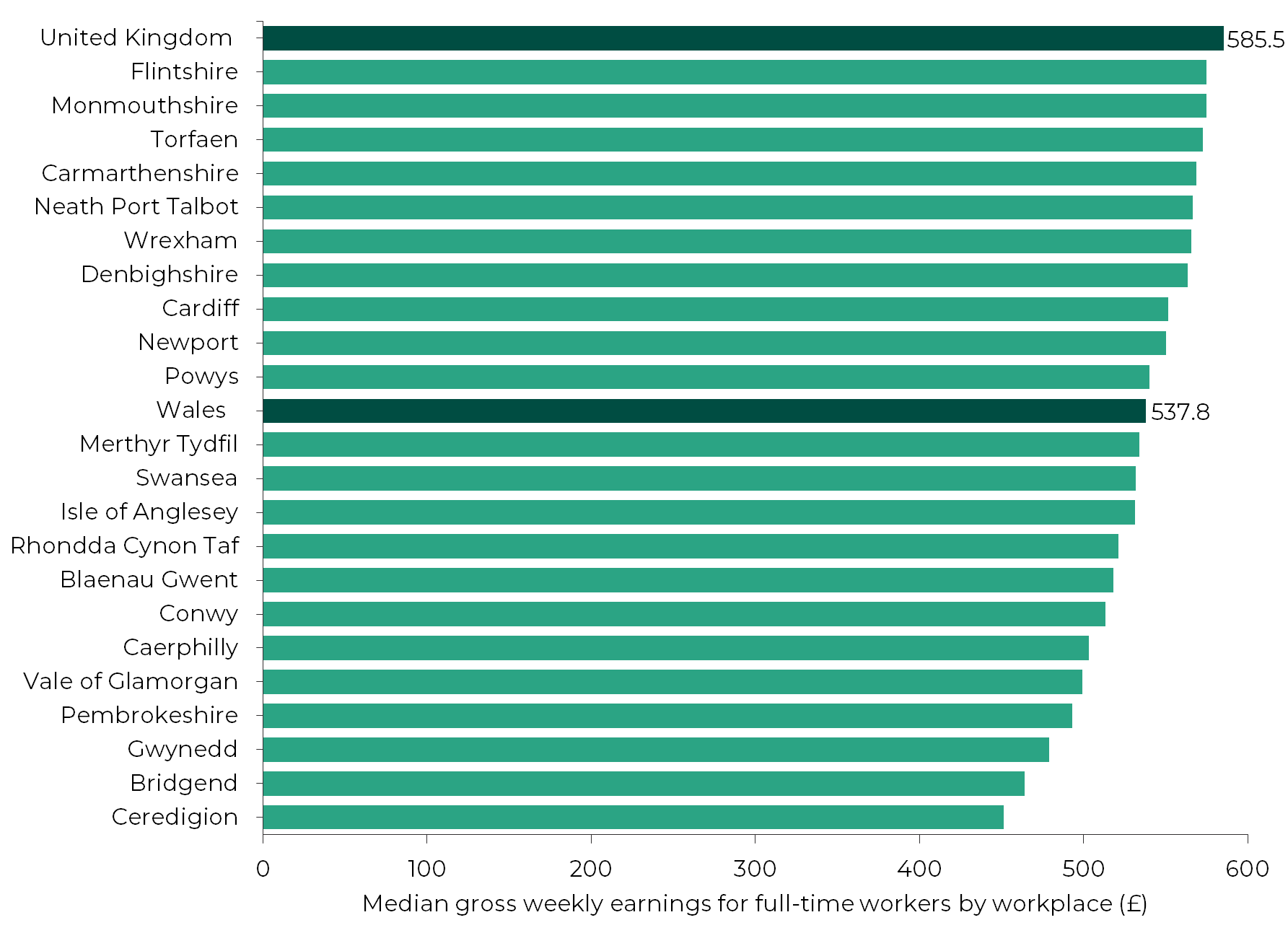

In April 2020 wages in Wales were lower than in all other parts of the UK except for Northern Ireland and North East England, contributing to the relatively high levels of in-work poverty identified by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. People working full-time in every Welsh local authority had median weekly pay lower than the UK average.

Median gross weekly earnings for full-time workers by workplace, April 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics, Employee Earnings in the UK: 2020

At the start of the pandemic, 22% of those working in Wales earned less per hour than the ‘real’ Living Wage with part-time workers and women particularly likely to do so. Many workers in key sectors such as social care and food retail earn less than the Living Wage, with the Resolution Foundation highlighting that this is the case for over half of frontline care workers.

The impact of the pandemic on low-income households

People from low-income households have been most likely to lose their jobs, lose income or to be furloughed since the start of the pandemic. The Resolution Foundation found that over 40% of the lowest earners had been affected in these ways, double the percentage of the highest earners. The Bevan Foundation highlighted that a quarter of Welsh households have seen their income fall during the pandemic, while at the same time living costs have increased for more than four in ten households.

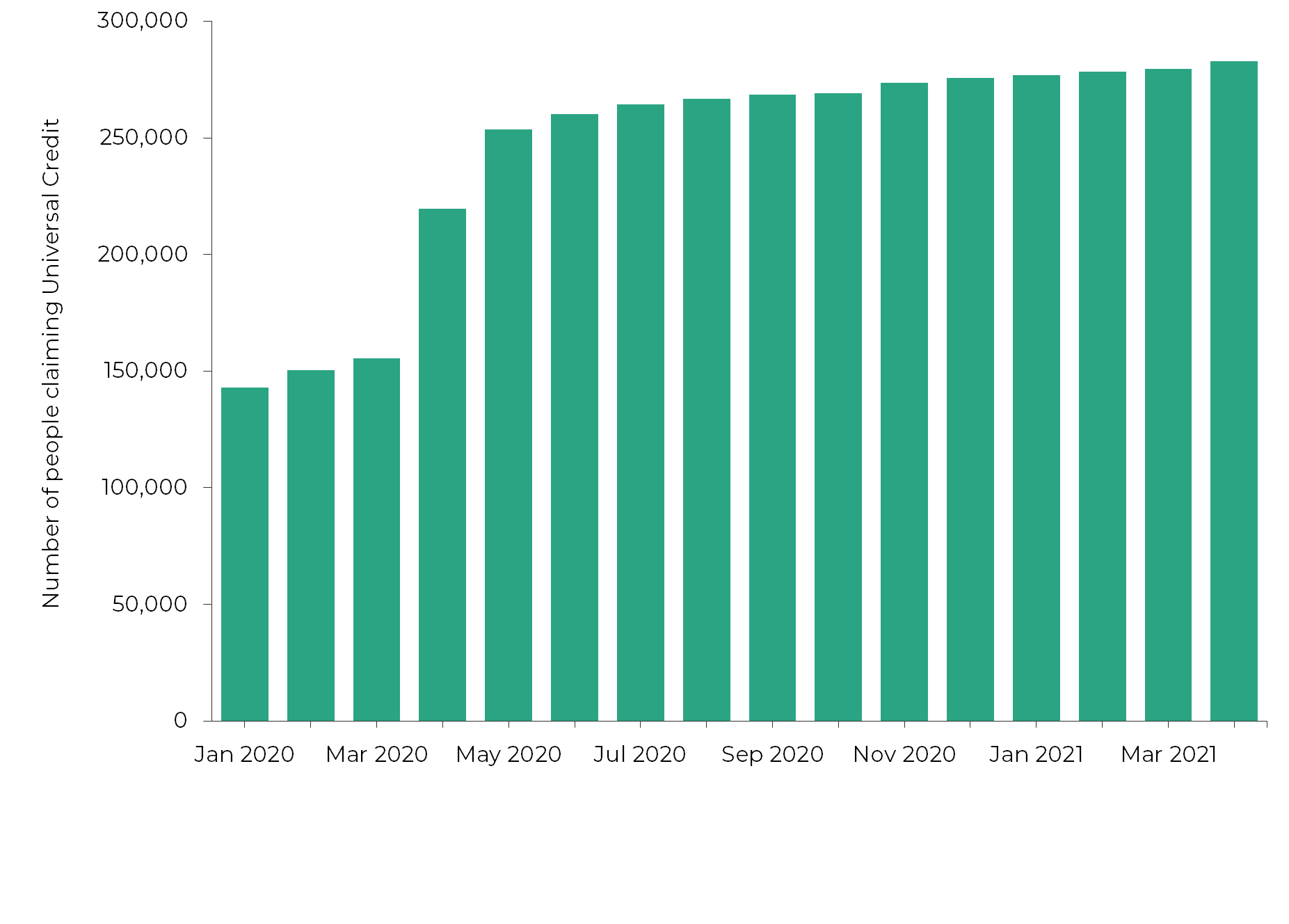

Consequently, the number of people claiming social security benefits which support those on low incomes has increased considerably. In April 2021 over 125,000 more people in Wales were claiming Universal Credit than at the start of the pandemic, with much of this increase happening between March and May 2020. The UK Government has temporarily increased Universal Credit by £20 per week until the end of September 2021, however it is unclear what will happen after this.

Number of people claiming Universal Credit in Wales, January 2020 to April 2021

Source: Department for Work and Pensions, Stat-Xplore Universal Credit data tables

There have been almost 180,000 COVID-related payments through the Welsh Government’s Discretionary Assistance Fund over the year to 18 March 2021. These are mainly due to people requiring to support as a result of stopping or reducing work, delays to benefit claims, or increased costs of living. Given that the fund has been considerably scaled up, the next Welsh Government will need to consider its future role.

Debt is likely to become a bigger problem in the coming months, as support schemes and eviction bans come to an end. Citizens Advice Cymru estimated that people in Wales have built up £73 million worth of household bill arrears during the pandemic, with the largest sources of arrears being rent and council tax. The Bevan Foundation found that low income households have been most likely to borrow during the pandemic, with over a quarter of the poorest households having borrowed from friends and family or gone into their overdraft.

The Bevan Foundation also found that more than a quarter of low income households have responded to difficult financial circumstances by cutting back on spending on food for adults. Food banks and the Welsh Government have stepped in to provide additional food to people shielding and those in need, with the Trussell Trust providing over 145,000 emergency food parcels in 2020-21. However, with many poorer households expecting to have to make further cutbacks in future the next Welsh Government will need to consider what action to take to support them.

What can be done to reduce poverty within the devolution settlement?

While Council Tax Benefit and the Discretionary Assistance Fund were devolved to Wales as part of UK Government welfare reforms, social security is predominantly non-devolved, with decisions being taken by the UK Government. Similarly, employment law is not devolved meaning that there are limits to the levers the Welsh Government can use to reduce poverty.

The Fifth Senedd’s ELGC Committee recommended that the Welsh Government should seek full devolution of Discretionary Housing Payments and explore the possibility of devolving other benefits, along with powers to top-up reserved benefits and create new ones.

A range of Welsh Government schemes operate alongside the social security system to provide assistance to people on low incomes. The Bevan Foundation and Joseph Rowntree Foundation have both called for the next Welsh Government to enhance these schemes to create a ‘Welsh Benefits System’. This would provide a single point of access for people on low incomes, and prioritise help with housing and education costs and emergency support.

To improve the economic position of those in low-paid work, the next Welsh Government will need to consider how the Fair Work Commission’s recommendations fit into its overall approach, and how it wishes to respond to issues facing low-paid workers that emerged during the pandemic.

The previous Welsh Government introduced an Economic Contract with fair work as one of its requirements for businesses seeking investment. The Wales TUC believes this should be strengthened to deliver better employment practices and other social and environmental outcomes, along with the introduction of fair work requirements for all procurement, grants and loans. FSB Wales has called for the next government to start a business-led campaign to help firms understand how fair work can operate alongside growing a business. The previous Welsh Government also published a draft Social Partnership and Public Procurement Bill, which would require the Welsh Government to set and achieve fair work objectives, and seek to use procurement to promote fair work and well-being.

To seek to deliver better outcomes for people on lower incomes, the previous Welsh Government introduced the Socio-Economic Duty from 31 March 2021. This requires public bodies covered by the duty to consider how their strategic decisions can help to reduce socio-economic inequalities by understanding potential impacts, and consulting with those impacted by decisions. While it is difficult to assess the impact of equality duties, this new tool has the potential to change how public bodies make decisions.

The key question for the next Welsh Government will be how effectively it can use these levers to help address widening inequalities resulting from the pandemic, while operating in the context of wider UK Government policy.

Article by Gareth Thomas, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament