This article was authored by Sarah Coe, visiting Senedd Research from the House of Commons Library.

Leaving the EU in 2020 meant the UK could find new ways to support farmers financially after decades under EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) rules.

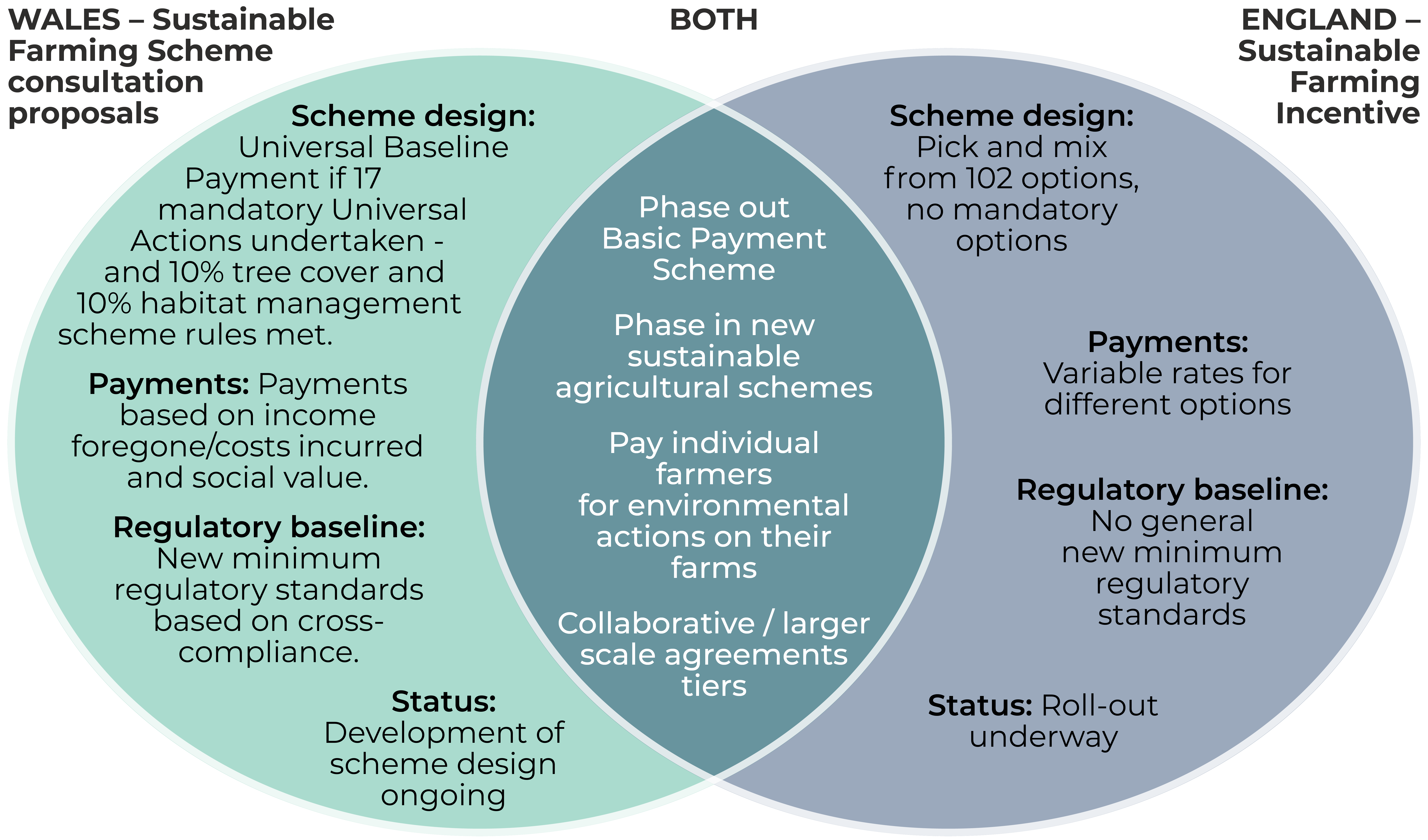

Agriculture is a devolved matter: each nation is taking its own approach, at its own pace. New and developing Welsh and English farm support schemes share the aim of promoting sustainable farming practices, but through different mechanisms and incentives. Both the UK Government and the Welsh Government say their new approaches recognise that producing food and protecting the environment go hand in hand.

This article looks at key things the two nations’ farming schemes have in common – and where they differ. Note, it considers the Welsh Government’s plans from its recent consultation, however these are subject to change. Differences between the schemes will be of interest for cross-border farms and also when considering the UK common market.

More detail on proposals for Wales can be found in the Senedd Research Briefing Sustainable Farming Scheme: 2024 update. The House of Commons Library Insight New approaches to farm funding in England provides information on English schemes.

How similar are farm funding plans for Wales and England?

Both nations’ new schemes will be based on the idea that farmers should be rewarded for providing environmental or other public benefits, rather than simply being paid broadly for how much land they farm.

Under the EU’s CAP, 80% of the UK’s farm budget went on area-based payments, known as Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) payments. To get BPS, farmers had to meet certain sustainability rules. The rest of the CAP budget went on rural support programmes, including agri-environment schemes such as the Glastir land management scheme in Wales, and Countryside Stewardship schemes in England.

Both countries’ governments plan to phase out BPS as they phase in new sustainable farming schemes.

In England, Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes are being rolled out. ELM has three tiers:

- the Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) pays farmers to adopt and maintain sustainable farming practices that recognise the importance of food production; protect and enhance the natural environment; and support farm productivity and resilience.

- Countryside Stewardship (CS) Higher Tier pays for more targeted actions on specific locations, features and habitats. CS was the main agri-environment scheme under the EU’s CAP. Higher Tier schemes are more complex while the Mid Tier CS agreements, suitable for most farmers, now come under SFI.

- Landscape Recovery pays for bespoke, longer-term, larger-scale projects to enhance the natural environment.

Wales is developing the Sustainable Farming Scheme (SFS). This will reflect Sustainable Land Management objectives to:

- produce food sustainably;

- mitigate and adapt to climate change;

- maintain and enhance ecosystem resilience; and

- conserve and enhance the countryside and cultural resources and promote public access and the Welsh language.

A temporary Habitat Wales Scheme replaced Glastir from 2024, to operate until the new SFS is in place.

What are the main scheme differences?

Wales and England have different timetables for change and have significant differences in scheme design.

In England, changes have already been made. Following the Agriculture Act 2020, BPS payments were reduced progressively and new schemes phased in under an agricultural transition period running from 2021-27:

- BPS reductions began in 2021 and the last scheme year was 2023. From 2024, farmers can claim ‘delinked’ payments based on their BPS payments without needing to own or farm land, and these will be progressively reduced to reach zero in 2027. Delinked payments for 2024 are 50-70% lower than a farmer’s average 2020-22 BPS payment (depending on the size of the farmer’s claim).

- SFI was piloted in 2021 and rolled out from 2022, with new actions added in 2023 and further additions in 2024. Payment rates have also increased.

In Wales, consultation is continuing. Following the Agriculture (Wales) Act 2023, in December 2023 the Welsh Government published a consultation on the SFS. It planned to:

- Start the transition to SFS in 2025, with full implementation in 2029. Farmers protested about the new scheme, in particular requirements on tree cover and the payment methodology. Subsequently, in May 2024, the new Cabinet Secretary for Climate Change and Rural Affairs announced the SFS Transition Period would start from 2026.

- Reduce BPS in steps, to 80% of current levels in 2025 and by another 20% each year to reach zero in 2029. However, given the delay to 2026, the Cabinet Secretary announced continuation of BPS payments in 2025, with details to follow.

Although both the Welsh and English schemes will pay farmers for the area of land they manage to certain environmental standards, there are fundamental differences in what farmers need to do.

England’s SFI scheme is a ‘pick and mix’ approach:

- Farmers can opt to take one or more of 102 SFI actions, most over a three year period, with different annual per hectare payment rates. For example, £13 per 100 metres for hedgerow management, or £798 per hectare for flower-rich grass margins. They can combine actions to build up total payments for their farm and can claim a management payment on top. In March 2024, the UK Government announced a cap so farmers cannot put more than 25% of their land into some SFI actionsto ensure the scheme is “supporting food production alongside delivering for the environment”.

In contrast, Wales is proposing an ‘all or nothing’ approach to receive payment:

- Farmers would receive a new ‘Universal Baseline Payment’ (UBP) per hectare provided they undertake all 17 Universal Actions and meet scheme rules for 10% tree cover and 10% semi-natural habitat. There would be exceptions depending on farm type - for example arable farmers do not need to undertake animal health actions. Details are awaited on the planned additional voluntary tiers of ‘optional and collaborative actions’.

- The Welsh Government says payment rates will be based on what it costs farmers to undertake the action and on ‘income foregone’ but has not yet published specific rates. It also plans a ‘social payment’ to reflect the value of a farmer’s actions to the community/environment, however details are not available.

Wales plans to maintain minimum regulatory standards that replicate the environmental requirements farmers have had to meet to receive BPS (known as cross-compliance). Cross-compliance ended in England at the end of 2023 and has not been replicated in regulations wholesale, although new 2024 regulations on hedgerow management reflect those specific cross-compliance rules.

What’s next for farmers in Wales and England?

In Wales, the new SFS scheme is delayed from 2025 to 2026. The Cabinet Secretary has set up a Roundtable with stakeholders to work out further details, with a sub-group looking specifically at carbon sequestration options. Plans are set out in the Welsh Government’s response to the SFS consultation.

The UK Government Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs continues to work with farmers and other stakeholders to improve schemes for England.

Top of many farmers’ concerns in England and Wales is how much money will be available for the new schemes.

The new UK Government has not yet set out farm budgets, although the Labour Party’s General Election manifesto said it would ensure effective introduction of ELMs. The Conservative Party manifesto pledged an additional £1 billion for UK farm support over next Parliament (up to five years) and the Liberal Democrat Party’s National Food Strategy pledged £1 billion more a year.

The future farm budget for Wales and the SFS will depend on funding from the UK Government. With previous disagreement between the UK Government and the Welsh Government on the level of EU-replacement funding for agriculture, budget allocation to Wales will be something to watch.

Figure 1. The differences and similarities between Welsh and English proposed/new farming schemes

Guest article by Sarah Coe, Senior Library Researcher, House of Commons