Holyhead’s Admiralty Arch marks the beginning of the historic main road to London. The marble monument has welcomed arriving ships, tradespeople and passengers since the early 19th century.

But since Brexit, truckers travelling to or from Ireland have also been welcomed by delays and bureaucracy, leading some to by-pass Welsh ports.

In March the last Welsh Government highlighted significant decreases in year on year volumes at Welsh ports, although more recent media reports suggest there has been some recovery.

As part of its efforts to level up communities across the UK, the UK Government plans to establish a freeport in Wales, alongside eight in England and one each in Scotland and Northern Ireland. These are intended to “drive forward investment and regeneration in some of the most deprived areas in the UK“.

However, the proposals have divided opinion on their potential impact on the wider economy.

What’s a freeport?

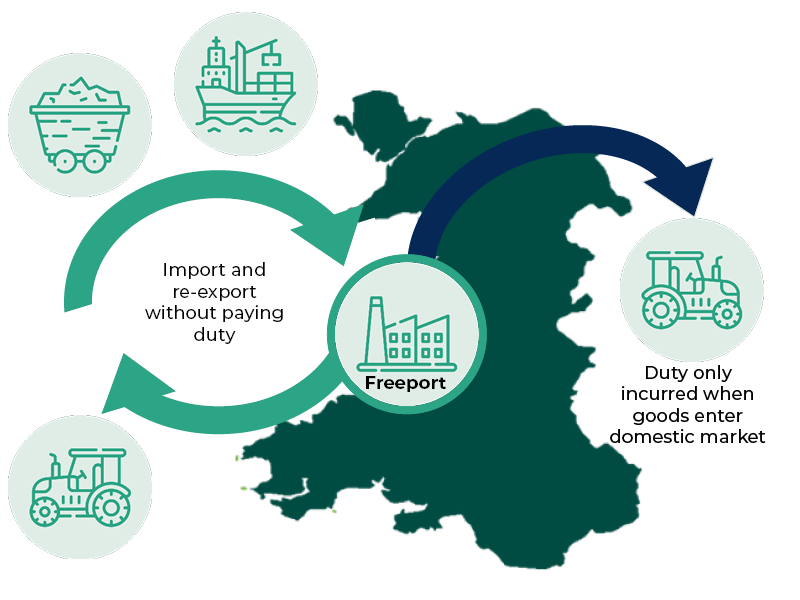

A freeport – or free zone – is an area within a country’s geographic border, but outside its customs area. They‘re usually located at, or next to, a maritime port or airport. Goods can be imported into, or exported out of, a freeport without incurring duty or taxes. Only when goods leave the freeport and enter the domestic market will duty or taxes need to be paid.

Manufacturing businesses operating in a freeport can benefit from ‘tariff inversion‘, when tariffs on a finished product are lower than those on its component parts. Further tax and non-tax incentives, such as lower rates for corporation or employment tax, as well as simplified customs processes, may also be offered.

Freeports aren‘t a new idea and have existed in one form or another since medieval times. Currently, there are around 3,500 free ports worldwide. Hong Kong, the Geneva Freeport in Switzerland, and the Jebel Ali Free Zone in Dubai are significant examples.

Seven freeports operated in the UK at various points from 1984. The final five were abandoned in 2012 when the relevant legislation expired, a fact attributed by some in part to the effect of EU regulation.

Freeports do exist in the EU. But, they must comply with state aid rules which, for example, limit the tax incentives offered. A 2006 United Nations report concluded that the EU “does allow the establishment of free Zones within its territory, but its definition of free zone is a very narrow one”.

The UK’s exit from the EU sparked new interest in freeports, most prominently by Rishi Sunak, now Chancellor of the Exchequer, writing in 2016.

What is the UK Government proposing?

The UK Government launched a Freeport Prospectus in November 2020, opening a bidding process to establish Freeports in England. The proposals include tax relief and capital allowances, expanded permitted development rights and support for innovation, as well as customs duty and tariff exemptions.

Alongside these proposals, the prospectus made clear that “working with the devolved administrations, the UK Government wants to establish at least one Freeport in each of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales”. The British Ports Association (BPA) has also said it’s working with the devolved administrations to develop proposals.

In his March 2021 budget, the Chancellor announced eight new freeports in England. But there’s yet to be any equivalent announcement for Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland

The case for and against freeports

Supporters of freeports argue that they foster economic growth and create jobs. In a statement to the House of Commons, the Chancellor said:

[Freeports] will allow us to drive forward investment and regeneration in some of the most deprived areas in the UK, delivering highly-skilled jobs for people across the country.

His 2016 report, The Freeports Opportunity, argued that UK freeports would capitalise on the strength of existing UK port infrastucture, potentially as significant job creators in often deprived port areas. He also suggested employment would focus on manufacturing, boosting that sector of the economy.

Critics fear freeports might not actually create jobs and economic growth, but merely relocate them within a country, benefiting freeport areas at the expense of other areas. It‘s argued that deregulation and a lack of oversight might harm environmental and labour standards, and freeports could make illegal activities like money laundering and tax evasion easier.

Critics also suggest that freeports may also come with considerable establishment and maintenance costs, offsetting at least some of the economic benefits.

The BPA says that freeports “must not cause economic displacement or create an unfair level-playing field“. Equally, it stresses that “Government plans have indicated that they will establish adequate controls to block illicit activity“ and that ports don’t wish to see “dismantling“ of employment or environmental standards.

It remains to be seen who‘s right.

Freeports in Wales

A number of Welsh ports have shown interest in becoming freeports, including Port Talbot, Swansea, Newport, Cardiff, Barry, Milford Haven and Holyhead. The last Welsh Government had been wary of the idea of freeports. The then First Minister, Mark Drakeford, said:

Freeports are not a policy of the Welsh Government. They have never been part of a manifesto that I have stood on, and I am not elected to introduce them. They are a manifesto commitment of the Conservative party at the UK level.

He explained that his government wouldn‘t object to freeports and was willing to enter constructive discussions. But, the then Deputy Minister for Economy and Transport, Lee Waters, called for Welsh freeports to receive the same level of financial support from the UK Government as English freeports. He claimed where English freeports would receive £25m, those in Wales would only receive £8m - a “Barnett share“.

The last Welsh Government was also concerned that a freeport might undermine environmental and employment standards. The Deputy Minister drew attention to the green ports model being proposed in Scotland, in which ports would commit to higher environmental and employment standards in return for tax and customs relief. He described this as “something we’re interested in as well“.

In evidence to the House of Commons Welsh Affairs Select Committee, Associated British Ports, which operates five ports in south Wales, advocated for establishing freeports in Wales. The Committee highlighted that the UK Government needs to cooperate with the Welsh Government, because significant policy areas such as port development, road infrastructure and land use planning are devolved. It said a Welsh freeport should not be created “purely for optical or political purposes”.

With eight freeports being established in England, very little known progress has been made on freeports in Wales. The last Welsh Government criticised the UK Government for proceeding before concluding arrangements with the devolved nations, and feared that economic activity might be displaced from Wales to England as a result.

Given this risk, the new Welsh Government may need to give early consideration to a future freeport for Wales.

Article by Matthias Noebels and Andrew Minnis, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Matthias Noebels by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council which enabled this Research Article to be completed.