This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

Even before pupils’ coats are back on their school pegs, the pressure is already on the education system to deliver significantly more. Concerns that we don’t stigmatise children mean that talk about a ‘lost generation’ needing to ’catch-up’ is already out of favour. Yet the inescapable reality is that months of face to face learning have been missed.

Our learners have been part of the pandemic’s "collateral damage" While at this stage there are more questions than answers, the solutions will need to be carefully considered and delivered during the Sixth Senedd.

The state of play pre-pandemic

Arguably, Wales was already facing an uphill struggle to secure good educational outcomes for all its learners. A decade after the then Welsh Government recognised that the education system had showed “evidence of systemic failure”, there was a collective holding of breath when Wales’ 2018 PISA results were announced.

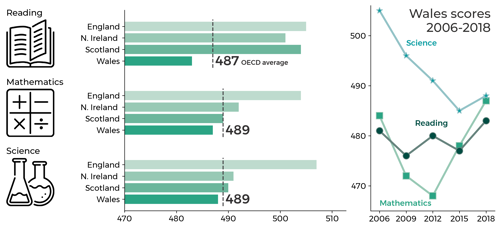

Following extra funding and a national action plan to deliver change, the 2018 PISA scores were seen as a much needed sign of some progress. Wales’ scores were no longer statistically significantly different to the OECD average in each of three main domains (reading, mathematics and science), although they remained the lowest of the UK nations. Then Education Minister, Kirsty Williams, described them as “positive, not perfect”.

How did Wales perform in PISA 2018?

Source: National Foundation for Educational Research, Achievement of 15-Year Olds in Wales: PISA 2018 National Report (2019)

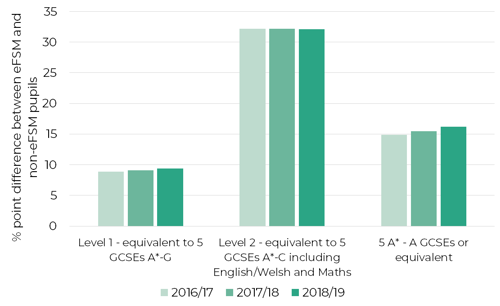

The most disadvantaged learners have extra challenges which can prevent them from achieving their full potential. Even though the previous Welsh Government invested £585 million since 2012 through the Pupil Development Grant (PDG ), the attainment gap it was seeking to close didn’t narrow. It also typically widens as learners get older. There’s a stark difference between children eligible for free school meals and their peers at Key Stage 4, the two years where learners usually take GCSEs and other examinations.

Attainment difference between pupils eligible for free school meals and their peers

Source: StatsWales

The extent to which the pandemic has affected learners

Children and young people themselves are well placed to give their verdict. A 2021 Children’s Commissioner survey of 20,000 children found that 35% didn’t feel confident about their learning, compared to 25% in May 2020. 63% of 12-18 year olds were worried about falling behind.

There are countless reports setting out adults’ views about how missing more than half a year of 'face to face' schooling has affected learners. One of the major concerns has been the variation between what schools have been delivering to pupils.

There’s a long list of potential impacts:

- ‘lost learning’ meaning pupils could underperform academically and have their long term prospects affected;

- a loss of confidence in the examination and assessment system;

- long term reductions in school attendance, a factor which we know is key to educational outcomes;

- difficult transitions between school years and from primary to secondary;

- challenges in re-engaging learners and addressing low motivation;

- an unhelpful ‘catch up’ narrative about lost learning placing unnecessary psychological pressure on children and young people; and

- a negative effect on learners’ ability and confidence to communicate in Welsh where they haven’t been able to do so at home.

As well as these obvious educational issues there are wider predicted effects. Current learners could earn less, with one estimate of up to £40,000 in a lifetime. The harm to children’s physical health and a higher prevalence of mental health issues, including anxiety and depression, are also serious concerns.

The pandemic’s wider economic impact is also likely to increase the number of children living in low income families. Again, it’s the most disadvantaged learners who are predicted to bear the brunt in the longer term. For example, in March 2021, the Child Poverty Action Group found that 35% of low-income families responding to its UK wide survey were still without essential resources for learning, with laptops and devices most commonly missing. The Fifth Senedd’s Children, Young People and Education (CYPE) Committee heard that there is “plenty of evidence” that ”there are striking differences between families in terms of their ability to support young people in their learning: the resources they have around them, the enthusiasm, the engagement, the commitment”.

There may also be work to be done to rebuild relationships which have been under significant strain during the past 12 months. Those between teaching unions and the decision-makers within the education system; between parents/carers and schools; and perhaps, most importantly, re-establishing the relationship between learners and their teachers.

Immediate and longer term solutions?

Some of the immediate solutions which are already on the table or up for discussion are: more money, including the ‘Recruit, Recover and Raise Standards funding’; more teachers and learning assistants on the ground; changing term times; and setting up summer schools, holiday clubs and home tuition.

However, in the longer term, there may be more questions than answers about the way forward, such as:

- How to ditch the ‘deficit model’? Placing the onus on the education system to support learners rather than pressurising learners to catch up.

- Whether a long term strategy is needed to coordinate the range of possible solutions? What’s the future role of schools, local authorities, regional consortia and the Welsh Government in this? Who should be in charge of this long term approach? Should Wales should appoint an Education Tsar, as in England?

- Are schools being properly funded? One estimate places the cost of Wales’ journey back from COVID-19 at £1.4 bn;

- Can international examples and historical experiences help identify ways of dealing with such major interruptions to education? One academic has already suggested that "disruption can lead to positive change if you're willing to make the effort".

- To what extent is the current education system fit for purpose? Is now the ‘watershed moment’ and time for a complete rethink?

Major reforms to deliver: mental health, the curriculum and additional learning needs

Children and young people’s return to the classroom has been heralded as the big chance to put their well-being at the heart of education. As well as having a positive impact on well-being, put simply, mentally healthy children are much more likely to learn.

Following pressure from the Fifth Senedd’s CYPE Committee and its stakeholders, Wales has already made a significant shift towards establishing a 'Whole School Approach to Mental Health'. The challenge during the Sixth Senedd will be to deliver it.

The potential sting in the tail is that, at the exact same time the education system is getting children back to school, it also has to contend with major legislative reform. This is in the form of wholesale changes to both the school curriculum and support for learners with Additional Learning Needs.

Some may argue that there’s been no better time to have such significant changes. If the education system can successfully implement these three major reforms then arguably Wales has done some significant leg work to be on a firmer footing to meet the challenges that COVID-19 has presented.

More questions than answers?

At this stage there may be many more questions than answers for the education system. The world into which learners will move has changed forever. Not only has the pandemic interrupted their schooling, but the future journeys they were expected to make into the workplace or further and higher education may be unrecognisable. The skills and aptitudes needed in the ‘new normal’ are only now beginning to be identified and are likely to be different from those needed before the pandemic began.

COVID-19 has made its unforgettable mark on the world. Perhaps the biggest question of all is how radical the response of Wales’ education system should be.

Article by Sian Thomas, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament