Should people convicted of crimes serious enough to warrant imprisonment lose their right to vote? Or do they retain their rights of citizenship even when imprisoned? Does the ban disproportionately affect certain groups of people? What is the purpose and effect of banning prisoners from voting?

These were some of the issues considered by the Equality, Local Government and Communities Committee in its recent inquiry exploring whether prisoners should be allowed to vote in Assembly and Welsh local government elections.

The committee undertook its work at the invitation of the Llywydd in the context of wider Assembly electoral reform. Responsibility for Welsh elections was devolved in 2017, and the Assembly is currently considering legislation to extend the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds, among other provisions.

What’s the current situation and why is it changing?

In the UK, most prisoners serving custodial sentences are banned from voting in all elections. The current provisions are in the Representation of the People Act 1983, but the disenfranchisement of prisoners dates back to 1870 when offenders were denied their rights of citizenship (known as ‘civic death’).

Prisoners on remand (either unconvicted or awaiting sentencing) are allowed to vote. People imprisoned for defaulting on fines, contempt of court, and (as of 2018) those on temporary licence or electronic tag are also allowed to vote. But as the Committee found, very few of these people are currently aware of their rights.

Since 2005 the UK’s ban has been repeatedly found in violation of international human rights law, as it applies regardless of length of sentence or gravity of offence. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) – which is not an EU body - considered the ban to be indiscriminate and disproportionate.

The judgments set off a political debate about the constitutional issues raised by such a ruling, including the UK’s relationship with the ECtHR, the nature of parliamentary sovereignty, and whether to reform the Human Rights Act 1998.

In 2017 the UK Government announced plans to give prisoners released on temporary licence or on home detention curfew (electronic tag) the right to vote in the UK. The measure affected around 100 prisoners, out of a total of 83,000 prisoners in the UK. The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, which oversees the implementation of judgements by the ECtHR, endorsed the UK’s actions as a proportionate response.

In April 2019 the ECtHR again found a breach of the Convention. This was despite the UK Government’s reforms as it related to elections before those changes. It is therefore still unclear if the UK’s current position will satisfy the ECtHR in the long term.

How did the Committee reach its conclusion?

The Assembly Committee received evidence from academics, charities, electoral bodies, the Victims’ Commissioner, prisoners, and held an public online discussion forum.

The following arguments against giving more prisoners the right to vote were considered by the Committee:

- Voting rights are not universal or absolute rights: the ECtHR has made it clear that some groups of people can be denied the vote. Some respondents thought that the current restrictions in the UK are fair;

- The public does not support voting rights for prisoners: the most recent (2017) poll of ‘Wales and the Midlands’ found that 60% of people are against prisoner voting (although this is a drop from 73% two years earlier);

- Voting is part of the ‘social contract’: some respondents, and the UK Government, argue that if people break the social contract by committing crimes, they cannot participate in democracy; and

- Prisoners are unlikely to take up the opportunity to vote: prisoners and prison staff told the Committee that take-up is likely to be low.

The following arguments for providing voting rights to more prisoners, or all prisoners, were considered by the Committee:

- Voting is a right not a privilege: some argued that imprisonment should not automatically remove the right to vote, and the presumption should be for as many people as possible to be included in democracy;

- Prisoners are still citizens: an argument in favour of greater enfranchisement of prisoners was that the removal of the vote signals that they are not part of society. Prisoners noted that they still pay tax on savings and any earnings while in prison, and deserve representation as a result;

- Public opinion: as noted above, public opinion is not in favour of prisoner voting, but there are signs that it is shifting. The 2005 ECtHR ruling stated that disenfranchisement should not be based “purely on what might offend public opinion”. The Minister told the Committee that sometimes legislation follows public opinion, and other times public opinion follows legislation (as with, for example, the smoking ban);

- Voting aids rehabilitation and reintegration: while the empirical evidence for this theory is limited, it is one cited by Lady Hale (now President of the Supreme Court). She said that any restriction of fundamental rights has to be in pursuit of a legitimate aim, and questioned whether the voting ban served as an additional punishment or whether it is intended to encourage a sense of civic responsibility. If it is the latter, it could be argued that this is more likely to be achieved by retaining the vote, to encourage reintegration into society;

- Prisoners receive public services and should be able to hold decision makers to account: prisoners still have an interest in public services, directly, and through their links outside of prison;

- International precedent: 21 Member States of the Council of Europe allow all prisoners to vote with no restrictions. 18 Member States (including the UK) allow some prisoners to vote. Eight Member States do not permit any prisoners to vote; and

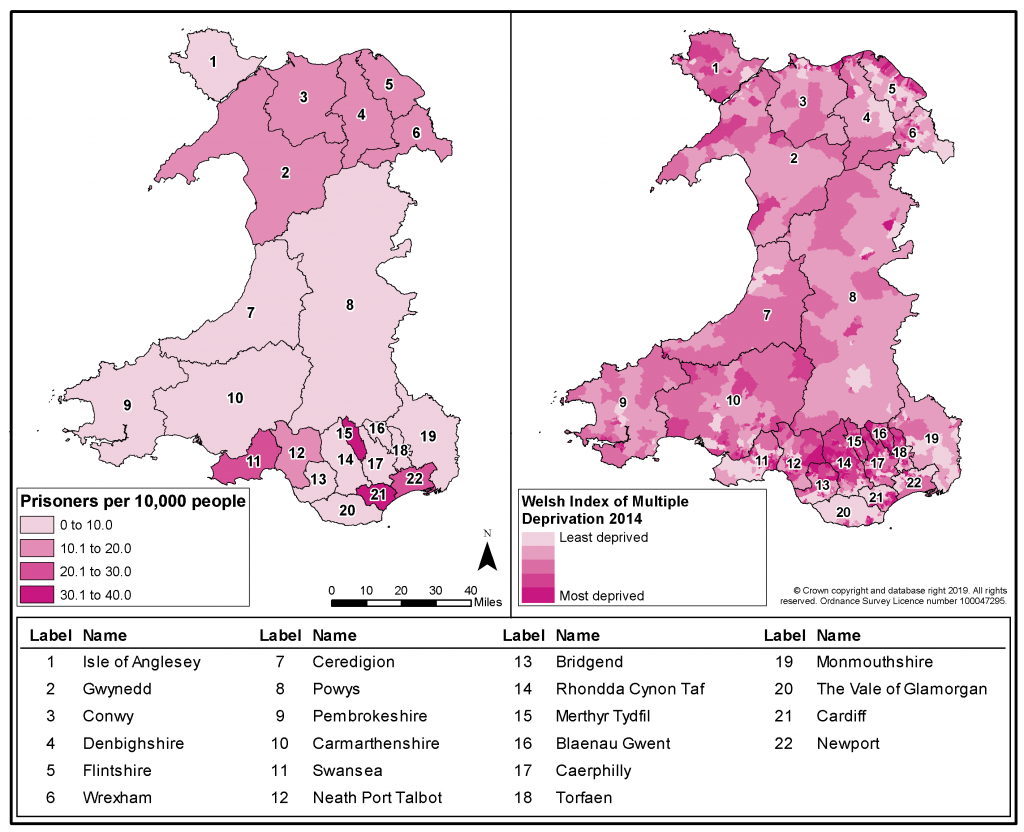

- The ban on prisoner voting disproportionately affects certain groups of people: Wales Governance Centre research found that Welsh people from deprived areas and BME communities are over-represented in the prison population, thus more likely to be disenfranchised. The Centre’s supplementary evidence showed that the rate of imprisonment is 2.8 times greater for people from the five most deprived areas in Wales compared to the rate recorded for the five least deprived areas. Although less than a third (28%) of Wales’ population lives in Blaenau Gwent, Merthyr Tydfil, Cardiff, Rhondda Cynon Taf, and Newport, almost half (49%) of all Welsh prisoners recorded a ‘home address’ in these areas.

Committee’s report / Research Service

Committee’s report / Research Service

The Committee also discussed whether the right to vote should be linked to sentence length, offence type, release date, or whether judges should be given the power to remove voting rights as part of sentencing. It decided that sentence length was the most appropriate way to determine eligibility.

One of the main practical issues is that 37% of prisoners with an address in Wales (1,740 prisoners) are held in 104 English prisons. The Committee recommended that prisoners should be registered at their most recent home address or with a declaration of local connection to determine their eligibility to vote in Welsh elections.

What did the Committee conclude?

The majority of the Committee recommended that prisoners with a home address in Wales serving total sentences less than four years should be allowed to vote in Welsh elections. Mark Isherwood AM and Mohammad Asghar AM did not agree with this recommendation.

The Committee’s report states:

We acknowledge some will think we have gone too far, and others that we have not gone far enough. However, we believe this is a compromise that will help with reintegration and the inclusion of prisoners as part of our wider society, ensure compliance with the ECtHR ruling, both by the letter and spirit of the decision, will not be unduly complex to administer and recognise public concern by not proposing every prisoner is entitled to vote.

[..] We believe [the recommendation] strikes an appropriate balance by widening the franchise in a way that excludes those sentenced for the most serious crimes. It also acknowledges sentencing policy in England and Wales, which considers sentences of four years or more as “long term”.

The Welsh Government agreed with the recommendation, and committed to introducing legislation before 2021 to allow prisoners serving less than four years to vote in local elections.

Currently, Section 12 of the Government of Wales Act 2006 provides that anyone eligible to vote in local government elections is eligible to vote in Assembly elections too.

But it is unclear how the Committee’s recommendation will be taken forward for Assembly elections.

In a subsequent letter to the Committee, the Welsh Government states that it does not believe “it will be possible to resolve these issues to include provision in the current Senedd and Elections (Wales) Bill” due to “significant legal and administrative issues”. It says that the Welsh Government will seek “an appropriate legislative vehicle to introduce provision [to allow prisoners serving sentences of less than four years to vote in Assembly elections] at the earliest opportunity”.

What’s the situation in the rest of the UK?

The Scottish Parliament’s equality committee recommended that the voting ban should be lifted in its entirety for Scottish elections.

After a consultation, the Government published a Bill in June 2019 that would allow prisoners serving sentences less than 12 months to vote, if passed.

The Scottish Government recently took remedial action to allow prisoners to vote in the Shetland byelection. The action was taken before the Bill passes through Parliament to abide by the ECtHR’s rulings in the short term.

There are currently no proposals to widen the franchise in England and Northern Ireland (where election issues are not devolved) beyond the groups of prisoners that are currently eligible to vote.

What now?

The Assembly will debate the Committee’s report and recommendations on Wednesday 25 September. Any change to the Assembly franchise (but not to the franchise for local government elections only) would need the backing of two-thirds of Assembly Members (a ‘super-majority’).

A local government Bill is expected in the Autumn, and the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Bill is currently progressing through the Assembly. Given the controversial nature of the issue, it will be interesting to see how prisoner voting reform for local and Assembly elections is taken forward.

Article by Hannah Johnson, Senedd Research, National Assembly for Wales