Brexit has brought a renewed focus on World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules, due to the possibility of the UK leaving the EU without a trade agreement in place. This blog post provides a brief overview of the WTO rules around agricultural support and import restrictions and what may happen post-Brexit.

Before the WTO was formed in 1995, there was an international agreement known as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Although the GATT is still in effect, the WTO has superseded it and updated a number of provisions. The WTO was set up to “ensure that trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible” and it currently has 164 members across the globe.

Any member of the WTO can pursue a dispute related to trade by any other member. The terms of membership of the WTO ensures the dispute automatically proceeds to court if not settled through negotiations between countries, with the whole process taking two to three years depending on whether or not an appeal takes place.

Production subsidies

The Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) was established to specifically address the issues in global agricultural trade. The AoA was signed in 1995, with the formation of the WTO, and contains three main pillars:

- Market access – the use of trade restrictions, such as tariffs on imports;

- Export competition – the use of export subsidies and other government support programmes that subsidise exports; and

- Domestic support – the use of subsidies and other support programmes that directly stimulate production and distort trade.

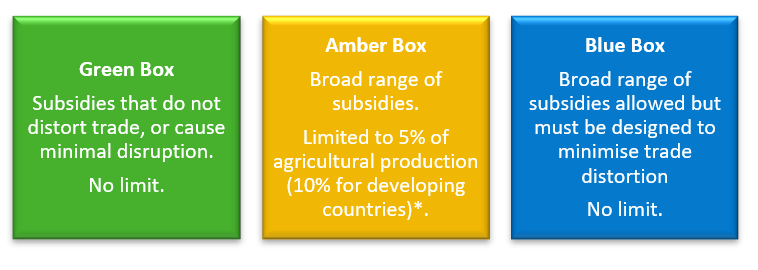

Within general WTO terminology, subsidies are identified by ‘Boxes’, with a traffic light system used to categorise the subsidies.

The different Boxes for agricultural subsidies are Green, Amber and Blue (shown in Figure 1 and explained below). There is also a ‘Developing Box’, which allows increased amounts of subsidy for developing nations, but it is not relevant to Wales. The AoA does not contain any Red Box subsidies which, in other sectors, indicate support that is forbidden.

Figure 1 - Subsidy types and their respective limits. *Exemptions apply for 32 WTO members including the EU.

Green Box

Green Box subsidies must not distort trade, or at most, cause minimal distortion. Green Box subsidies are not capped, provided they comply with the criteria set out in Annex 2 of the AoA. Green Box subsidies tend to not be directly linked to a specific product but can include direct income support not related to production levels or prices. They can also include environmental protection and regional development programmes.

Amber Box

Amber Box subsidies include measures to support prices, or subsidies directly related to production quantity and are therefore trade distorting. The Amber Box covers a broad range of subsidies.

Amber Box subsidies are subject to limits: “de minimis” minimal supports are allowed. This is generally capped at 5% of agricultural production for developed countries and 10% for developing countries. However, there are certain exemptions above this level for 32 WTO members, including the EU, which can exceed the de minimis support as it was already above the limit before the agreements were put in place. This level of support is expressed in terms of a “Total Aggregate Measurement of Support” (Total AMS).

Blue Box

The Blue Box subsidies can be seen as the ‘Amber Box with conditions’. For example, there may be a limit on production to reduce trade distortion. Currently there are no limits on the Blue Box subsidies.

WTO subsidies and Brexit

Leaving the EU means leaving the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and its related support. Both the UK and Welsh Governments have recently published consultations regarding the future of land management in the UK. Both propose future payment schemes based on “public goods”. Public goods could be environmental or local economic benefits, which are considered in Annex 2 of the AoA.

Currently under the AoA, the level of payments under the environmental and regional development programmes is restricted to “the extra costs or loss of income involved in undertaking agricultural production” (also known as “income foregone”). It is currently unclear how environmental benefits, that cannot be directly sold on the market, would be treated under income foregone.

Dr Ludivine Petetin, from the School of Law and Politics at Cardiff University, argues that if the UK pursues a “radical change” in agricultural policy that retains the EU’s interpretation of income foregone while also ending Direct Payments – it is likely that the bottom 25% of English farms that currently only survive because of CAP support will disappear. She says this scenario could be worse in the devolved countries since they rely more heavily on CAP payments.

Depending on negotiations, the UK may need to use the de minimis principle for Amber Box subsidies or it may receive a share of the EU’s Total AMS support allowance. Subsidies within the Amber Box are less likely to be challenged by WTO members as it is accepted that they are trade distorting.

Dr Petetin argues that Amber Box subsidies should be used for a transition period post-Brexit, as it will allow a pathway from area based subsidies to environmental outcomes based payments. She states that relying on the Amber Box for a transition period only (rather than indefinitely) would be more politically acceptable to WTO members who do not benefit from the AMS. She believes that Blue Box subsidies are unlikely to be used for post-Brexit agricultural support.

Import restrictions

Article XX of the GATT contains a number of “general exceptions” that governments can use to regulate imports even if those measures would normally be inconsistent with WTO rules. These general exceptions can be applied for the purpose of preserving public morals; protecting human, animal or plant life or health; and conserving of natural resources.

There are two other specific WTO agreements that consider food safety, and animal and plant health and safety:

- The Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Agreement ensures standards are based on science, are only applied to the extent necessary, are non-arbitrary and non-discriminatory.

- The Technical Barrier to Trade Agreement is designed to ensure that regulations, standards, testing and certification procedures are not used to limit trade.

For all of these agreements, the WTO encourages international standards as it believes they are “less likely to be challenged legally in the WTO than if it sets its own standards”.

Import and export restrictions after Brexit

Immediately after the UK leaves the EU, standards will be aligned with EU rules and standards. Depending on the final trade agreement, it is then for the UK and Welsh Governments to decide whether to keep the current EU regulations or change them. If the UK trades under WTO rules then any new rules, that are different to the EU, could lead to non‑tariff barriers between the UK and EU.

Food standards in the UK are currently considered some of the best in the world, and currently meet or exceed EU standards. However, the Institute for Government suggests, that even if these high standards continue in the future, in the absence of formal recognition of the UK’s regulations as being equivalent to the EU’s, there could be an issue for both imports and exports with the EU as:

There is a difference between having the same rules and having those rules legally recognised as being the same as the EU’s.

In this instance, the EU would be required by its own laws to treat the UK as a third country. That means UK businesses would face regulatory barriers and customs checks in doing business with the EU.

The Assembly’s Climate Change, Environment and Rural Affairs Committee considered agricultural trade and standards in its report; The Future of Land Management in Wales (March 2017). The House of Commons Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee also considered these issues in Brexit: Trade in Food (February 2018).

To stay up to date with what the Assembly is doing in relation to Brexit, you can follow the new Assembly and Brexit pages.

Article by Chris Wiseall and Katy Orford, National Assembly for Wales Research Service

The Research Service acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Chris Wiseall by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council which enabled this Research Briefing to be completed.