According to the State of Nature 2019 report, wildlife in Wales continues to decline, with the latest findings showing that 17% of species in Wales are at risk of extinction.

What is the State of Nature report?

The report presents the status of UK wildlife, focusing on changes in biodiversity and the drivers of these changes. Conservationists and researchers from over 70 organisations joined with government agencies to produce the latest report, following previous reports in 2013 and 2016.

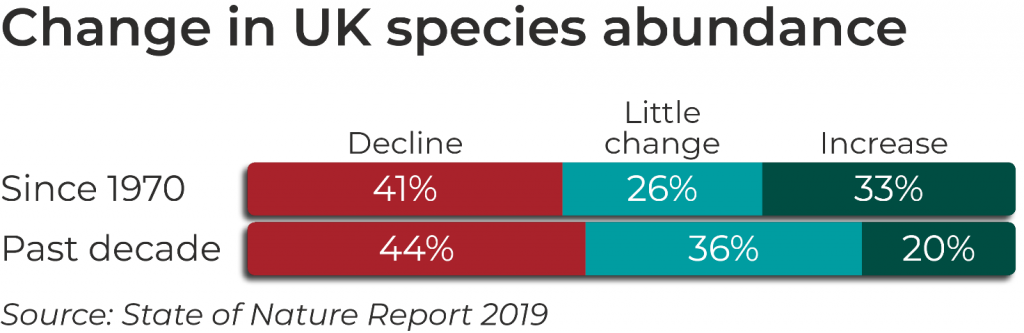

The report states that owing to the huge effort by wildlife recorders, we know more about the UK's wildlife than any other country. The report reveals that since scientific monitoring of UK species began in 1970, there has been a 13% decline in the average abundance of wildlife,with 6% of that fall happening in the past decade. On average the distribution of UK species has declined by 5% since 1970, with 2% loss happening in the past decade. Overall, the report shows that across the UK there are fewer numbers, of fewer species, in fewer places.

What are the key findings?

Changes in species abundance

Since 1970, 41% of UK species have declined in abundance.

Since the 1970s, butterflies and moths are among the species that have suffered the greatest falls in abundance in the UK, with declines of 16% and 25% respectively. The abundance of habitat specialists have declined further, for example the high brown fritillary and grayling butterflies have declined by around 75%.

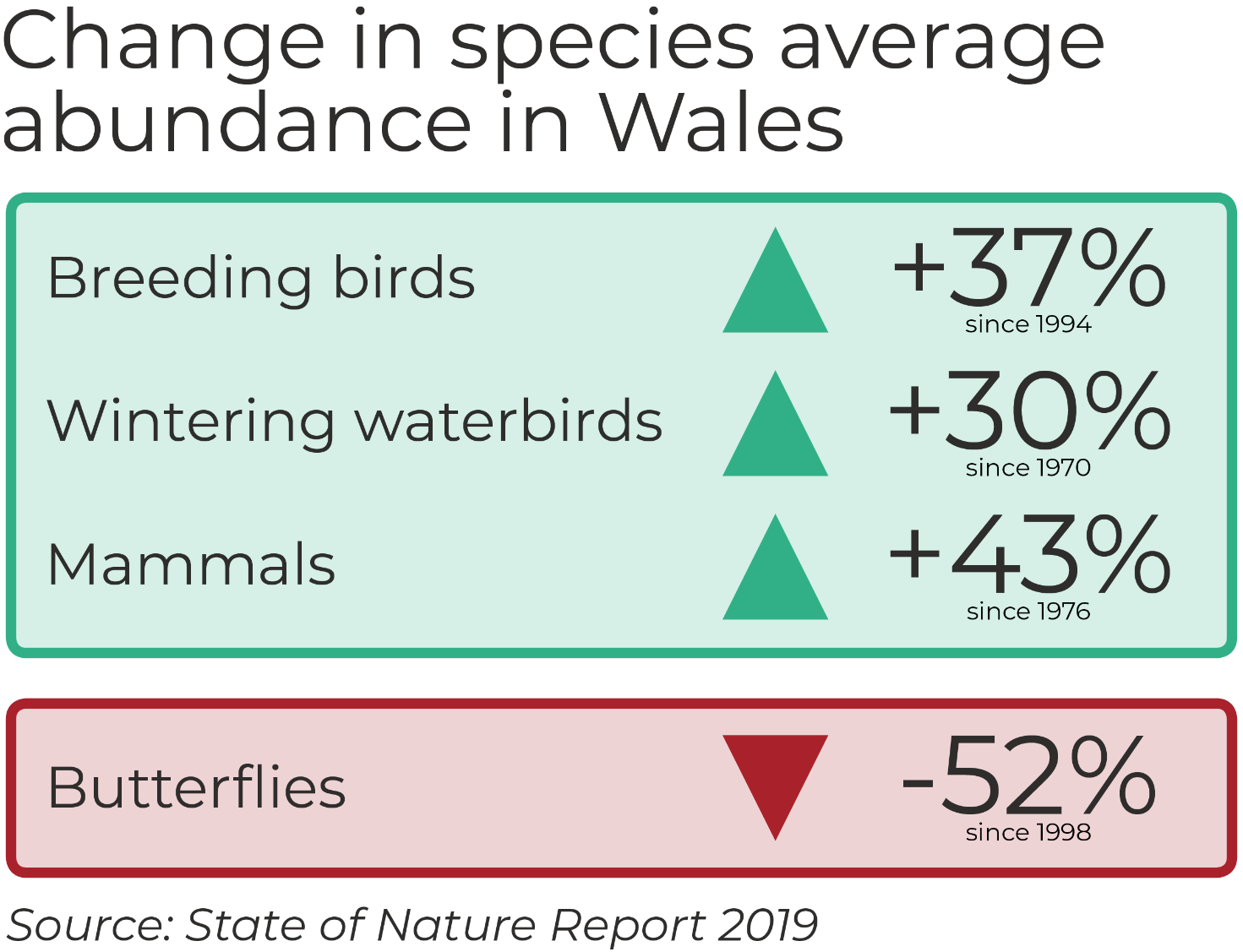

Due to limited data, there is no overall average figure for changes in species abundance for Welsh wildlife. However there is data on certain groups: the average abundance of butterflies has declined in Wales since 1976, while average trends in mammals and some bird groups are increasing.

Changes in species distribution

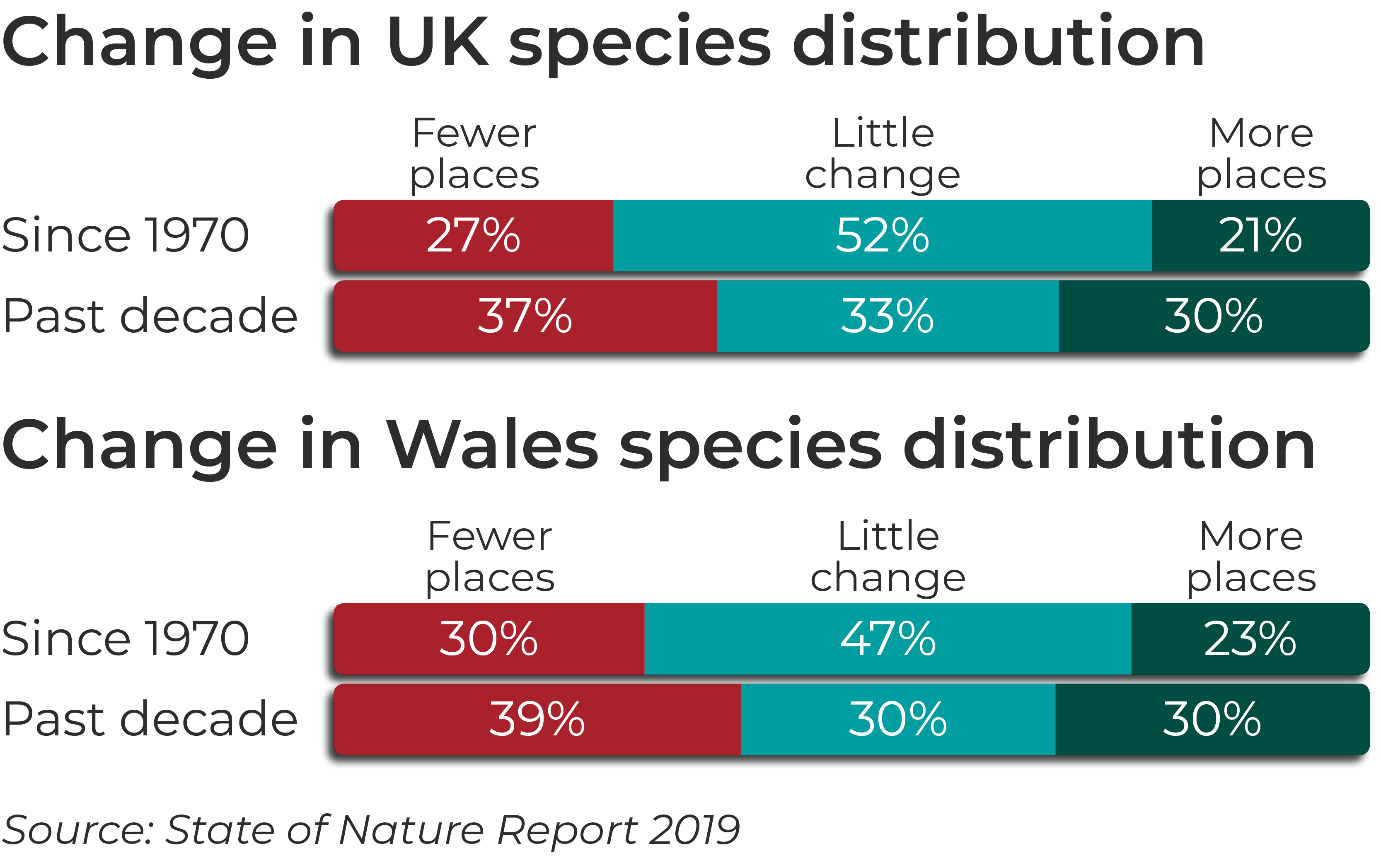

There have also been big changes in where wildlife is found. For example, in the UK the distribution of mammals has decreased by 26% since the 1970s.

Wildlife in Wales has also been found at fewer sites, with a 10% fall in average species distribution since 1970. This is double the rate of average species distribution decline (5%) seen in the UK as a whole.

Extinction threat

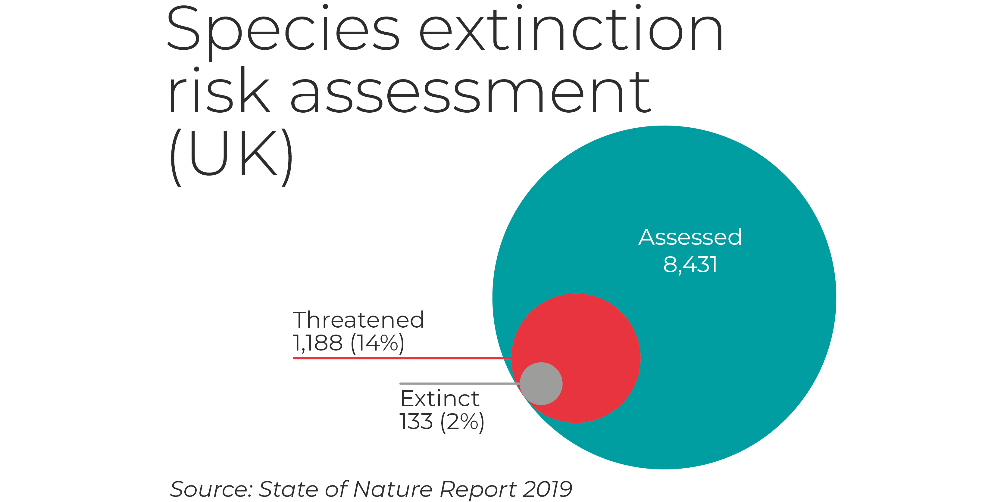

Of the 8,431 species in Great Britain assessed by the IUCN Regional Red List, almost 1 in 7 are at risk of being completely lost. The two mammal species most at risk of extinction are the Scottish wildcat with approximately 300 remaining and the greater mouse-eared bat with only one male left in the UK.

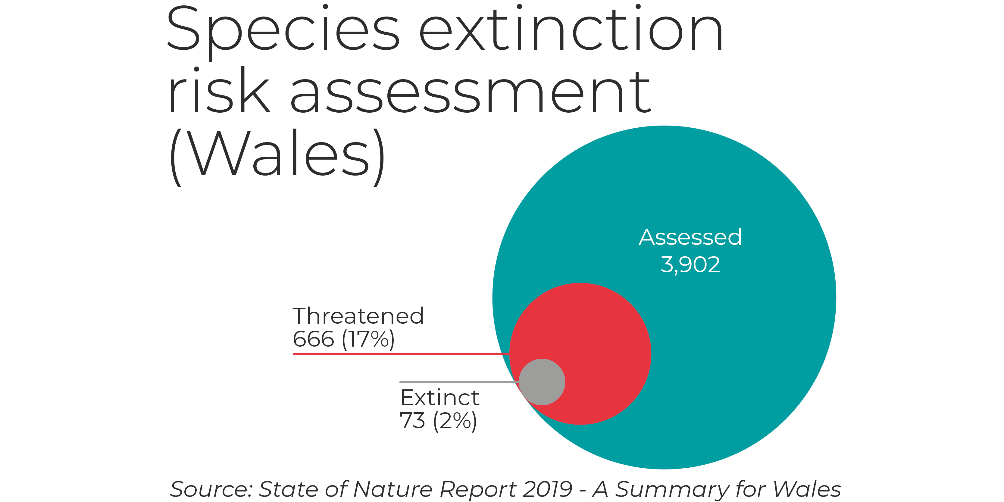

Looking more closely, of the 6,500 species found in Wales and assessed by the IUCN Regional Red List, 523 (8%) are at risk of extinction from Great Britain. Looking at Wales specifically, there is enough data on 3,902 species to assess their risk of extinction within Wales, with almost 1 in 6 species at risk of disappearing. Turtle doves and corn buntings have already been lost from Welsh skies.

Welsh land mammals also fare badly, with 13 of the 44 mammal species (32%) assessed for the report at risk of disappearing altogether from Wales, including the red squirrel and water vole which were once widespread.

The number of species found in Wales threatened with extinction has increased slightly from the previous State of Nature 2016 report, where 7% were at risk of extinction, compared to 8% in 2019.

What is causing wildlife declines?

The report highlights that the major pressures that have caused the loss of wildlife include farm management, woodland management, pollution from fertiliser and plastic, increasing urbanisation, hydrological change, climate change and invasive species. It states that at sea, climate change and fishing have the greatest impact upon marine biodiversity.

Changing agricultural management was identified as having the greatest single impact on nature. The report highlights that with 72% of UK land used for farming, and 88% in Wales, there is less space for wildlife to exist free from the influence of agricultural practices. Changes to land management in Wales have caused the loss of more than 90% of semi-natural grassland habitats since the 1930s, negatively affecting species that rely on this habitat.

The report points to reductions in funding which it says have constrained the ability of public sector organisations to conserve nature and prevent further declines. It states that in 2008/09 government funding towards biodiversity was £686m, but has since dropped by more than 30% to 456m in 2017/18.

What does this mean for wildlife in Wales?

Positive features

Although the report claims the figures are mainly “cause for alarm”, there is “room for cautious hope”. Woodland cover has almost quadrupled across Wales, from 4% in the early 1900s to 15% today. Polecats are also making a “slow recovery” from a low point in the 1930s.

Furthermore, there are a range of conservation initiatives aiming to help nature restoration, for example the Celtic Rainforests Wales EU LIFE project aims to protect and enhance the ancient Western Atlantic Oakwoods of Wales.

The report goes on to highlight efforts by conservation organisations and individuals that have saved various species from extinction. For example the bittern and the large blue butterfly were brought back from the brink of extinction in Wales.

Where the need for improvements have been identified

The report explains that agri-environment schemes (AES) in Wales, designed to pay farmers for helping nature and reversing wildlife declines on farmland, have only been "partly successful" in achieving their biodiversity goals. This is partly due to a 21% decline in farmland area participating in a higher-level AES scheme.

Although 11% of land in Wales is within sites that are officially protected for nature conservation, the majority are not in a good condition or well managed for wildlife. The Welsh Governments Natural Resources Policy (PDF, 967KB) acknowledges that improving management of these protected sites is crucial for creating resilient ecological networks that can deliver nature recovery and benefits for people.

The report also highlights that the 139 Marine Protected Areas designated by the Welsh Government require more work to ensure that they are being managed effectively for nature.

Welsh Government policy

The UK, Wales and other devolved nations have policies and legislation in place to protect and restore nature.

In Wales, this includes the Environment (Wales) Act 2016, the Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, and Welsh Governments Nature Recovery Plan.

The Welsh Government has produced a draft Welsh National Marine Plan that includes policies to deliver environmental objectives including expanding Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). On 29 April 2019 the Minister for Environment, Energy and Rural Affairs, Lesley Griffiths AM declared a climate emergency in Wales and the Welsh Government has policies in place to meet carbon emission reduction targets.

In summary…

Although the UK and Welsh governments have a range of policies to protect and restore nature, overall species have declined in abundance and distribution, with approximately 1 in 7 species threatened with extinction across the UK. The 2019 State of Nature report shows there has been no significant improvement in the condition of nature since the 2016 report which described the UK as “among the most nature-depleted countries in the world”.

Article by Claire Stewart and Katy Orford, Senedd Research, National Assembly for Wales

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Claire Stewart by the Natural Environment Research Council which enabled this article to be completed.