The First Minister’s five priorities, as set out in his Welsh Labour leadership campaign, included a commitment to ‘Give all children in Wales a strong start, focusing on the first 1,000 days of a child’s life’.

In the first of two articles, we look at the factors influencing children’s health from birth, any disabilities they may have and any complex support needs they may develop. Our second article will look at services and support for disabled children in the first 1,000 days.

This article discusses premature birth and disability. Readers are advised that they may find some of the content distressing.

Developments in medical care

Survival rates for premature babies and those with low birthweights have risen significantly in the last 30 years due to advances in specialist neonatal care. Whilst survival rates have increased, prematurity is linked to disability and poorer health outcomes.

Between 2006 and 2019, increasing survival rates from ‘extreme prematurity’, defined by the World Health Organisation as births occurring before 28 weeks, led to changes in the guidance for the resuscitation of babies, to include those born as early as 22 weeks.

Approximately 10% of singleton babies born at 22 weeks with low birthweight survive. Of those babies who receive intensive treatment, 30% survive, according to studies in high income countries. For babies born at 24 weeks, survival rises to around 60%.

In Wales, 8.2% of live births in 2022 occurred before 37 weeks, out of the total of 28,388, which is the lowest number of live births since 1929. Births before 37 weeks as a percentage of all births increased by 0.2 percentage points since 2021 and 1.1 percentage points since 2013.

Birth weight and prematurity are closely linked and risk factors include:

- Maternal age: close to one in five babies are born pre-term when the mother is aged either under 16, or 45 and older.

- Ethnicity: the percentage of babies from Asian ethnic backgrounds with low birthweight has been on a broad upward trend and reached 9.2% in 2022.

The percentage of live single births with a birthweight of under 2.5kg, which is considered ‘low birthweight’ is one of the national indicators published to measure the progress of the Well-being of Future Generations Act 2015 . In 2022, 7.2% of all births had low birthweight. This was 0.4 percentage points higher than in the previous year and 0.3 percentage points higher than in 2013.

Whilst the increase in survival rates for premature and low birthweight babies provides hope and a positive outcome for many parents, supportive counselling is recommended by the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAMP) regarding the potential implications of prematurity. People’s perceptions of impairment and disability vary. It is often societal attitudes and environments, which can themselves be the main ‘disabling factors’, and which the ‘social model’ of disability aims to counter.

- 1 in 10 premature babies will have a permanent disability such as lung disease, cerebral palsy, blindness or deafness.

- 1 in 2 premature babies born before 26 weeks of gestation will have some type of disability.

- 22% of babies born before 26 weeks will have a severe disability (defined as cerebral palsy and not walking, low cognitive scores, blindness, profound deafness).

Most premature babies grow up without severe disability and the rates fall from 1 in 3 below 22 weeks to 1 in 10 at 26 weeks. However, for those born before 26 weeks, 80% may have some degree of additional need.

Mild to moderate needs may only become apparent as children grow older and mean, for example, that they need extra help in school or have mobility problems. According to the BAMP, children who were born prematurely may develop social and emotional problems.

Survival rates have also increased for babies born with a range of congenital conditions including genetic conditions. These can have varying impacts on children’s physical and intellectual development. Improved medical care means that 97% of babies born with a congenital abnormality will survive to at least 1 year of age. Approximately 4.8% of all births in Wales in 2022 were affected by a congenital condition leading to disability (the true figure may be nearer 5.1%)..

Increases in neurodevelopmental disabilities

When there are concerns about a child’s development in the first 1,000 days, they may be referred to a community paediatrician or other health professional for investigations and support.

Neurodevelopmental disabilities are medically defined as a group of behavioural and cognitive disorders arising during development which impact the function of the brain. These can affect a child’s intellectual ability, motor skills, language and social behaviour.

An understanding of Neurodiversity is that these traits are part of the naturally occurring range of differences in individual brain function and behaviour, part of the normal variation in human populations.

Conditions within the umbrella of neurodiversity include autism, ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD), specific learning difficulties (dyscalculia, dyslexia), Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) or dyspraxia and Tic disorders (including Tourette's syndrome).

It is widely reported that around 15-20% [around 1 in 7] of people in the UK are neurodivergent. There is currently no comprehensive data source for neurodevelopmental diagnoses in Wales however across the UK as a whole there has been a 787% rise in autism diagnoses over 20 years. Reasons for this rise are likely due to a number of complex factors.

Some individuals who are neurodivergent view themselves, or may be viewed by others, as having a disability, and may have additional learning needs, or a coexisting learning disability. Young children with a range of complex needs may be under the care of paediatric services before they receive a diagnosis.

Our recent briefing gives further information about neurodevelopmental services.

Poverty, disability and the first 1,000 days

The First Minister has framed his commitment to the first 1,000 days in the context of tackling poverty, that will “require a long-term and co-ordinated response across Government, across public services and, indeed, across Wales”.

All families in Wales have faced increases in the costs of essential goods and services., which Public Health Wales says follows a “sustained reduction in welfare benefits available to families with children since 2010” and that “insecure work and high childcare costs are compounding the risk that increases in the cost of living pose to children’s health and well-being”. The wider determinants of health, such as food insecurity, fuel poverty, transport poverty and the environment are known to impact children disproportionately and lead to poorer outcomes in adulthood.

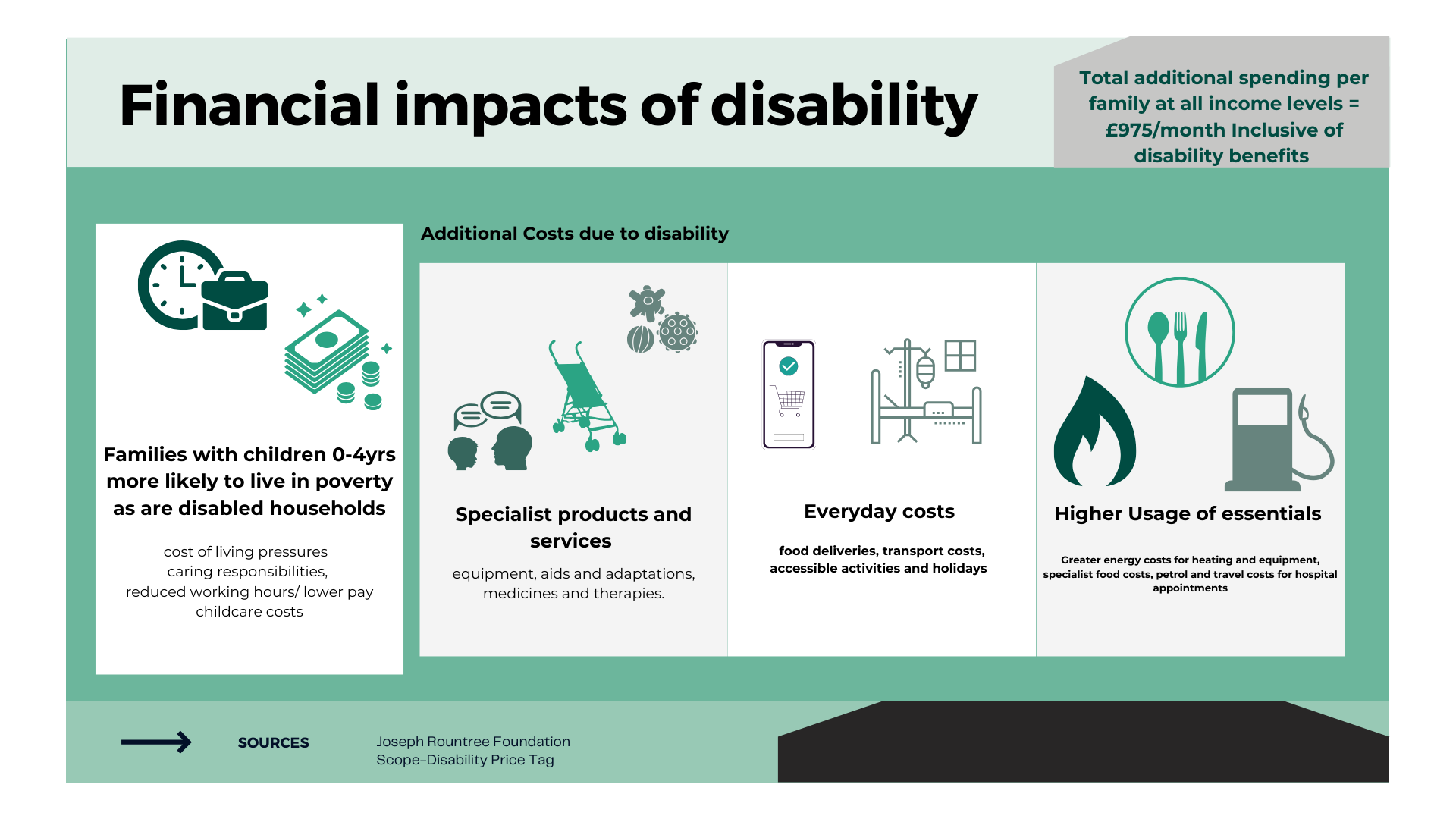

Children in families that include someone with a disability (child or adult) are more likely to live in poverty (31%) than those in households with no disabilities (26%). Against this background of disadvantage, the additional increased spending incurred by families with disabled children amounts to a ‘Disability Price Tag’, estimated by the disability equality charity, SCOPE, to be £975 per month.

Reductions in household income mean the everyday essentials needed for children’s health and development become harder to afford. For children with existing vulnerabilities due to disability, these social disadvantages can accumulate, compounding mental health and well-being issues later in life. Addressing child poverty would therefore seem essential to reduce the disproportionate impact of health inequalities on disabled children.

Article by Sarah Hayward, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament

Senedd Research acknowledges the parliamentary fellowship provided to Sarah Hayward by the Economic and Social Research Council which enabled this article to be completed.