In this guest blog post, Emma Rose from the Sustainable Food Trust, presents results from the Trust’s recently published study, The Hidden Cost of Food (PDF 23.9MB).

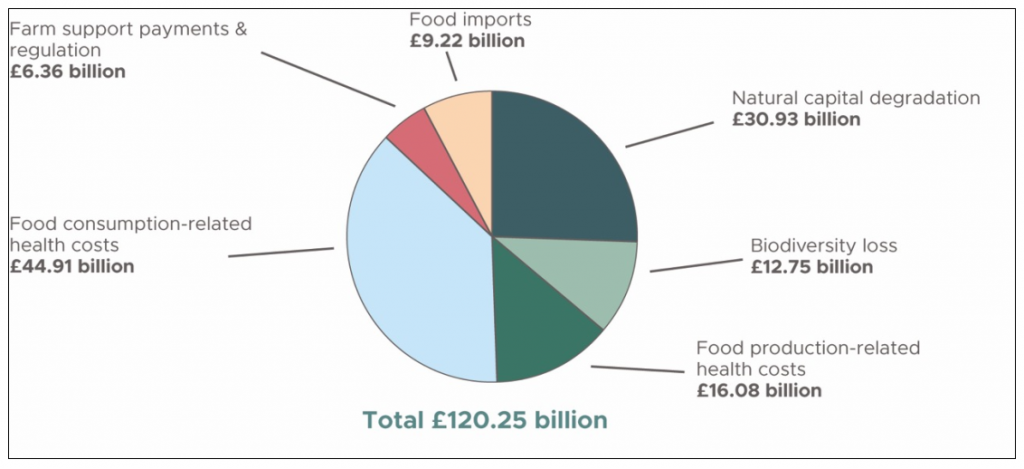

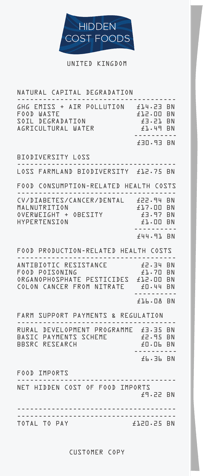

The study provides an overview of the cost of what the Trust describes as the “negative externalities” of the UK food system. Based on an extensive review of published evidence, it estimates that the food system generates additional costs of £120 billion, in addition to the £120 billion spent annually on food by consumers. The Trust suggests these costs are passed on to society in a number of ways.

Study findings

The total cost of food system externalities identified in this report is almost 30 times higher than previous estimates have indicated. The study concludes that, for every £1 spent on food, additional ‘hidden’ costs of £1 are incurred.

The total cost of food system externalities identified in this report is almost 30 times higher than previous estimates have indicated. The study concludes that, for every £1 spent on food, additional ‘hidden’ costs of £1 are incurred.

The largest proportion of the hidden food system externality costs are production-related costs, attributable to the impacts of intensive production methods such as environmental pollution, natural resource depletion, soil degradation, biodiversity loss and some health impacts. Together, these make up an extra 50p for every £1 spent on food.

The study suggests the emergence of a food industry devoted to the marketing and sale of highly-processed food products has exacerbated the consumer trend towards consumption of unhealthy food, and the associated food-related ill-health externalities identified in this report. Food-related healthcare costs linked to poor diets - such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, dental cavities, malnutrition, hypertension, overweight and obesity - account for an extra 37p.

In addition:

- Food imports to the UK account for an extra 7.8p for every £1 spent.

- Regulatory, administrative and research costs were found to account for a further 2.7p of every £1 spent on food in additional ways.

- Farm support payments account for 2.5p in every hidden £1 spent on food.

The study concluded that these external costs are paid by citizens in a number of ways; through general and local taxation, private healthcare insurance, lost income, and charges from water companies – partly to cover the costs of reducing levels of certain pesticides and nitrate in drinking water to legally acceptable levels.

What’s the problem with hidden costs?

In the presence of hidden externalities, the Trust concludes that the full costs of an activity are not incorporated into the balance sheets of the businesses that incur them, nor are they reflected in the retail price of food - making it difficult for citizens to make good choices about what they eat.

The externalisation of these costs weakens the business case for most food producers, processors or retailers to invest in more sustainable practices. Equally, businesses who adopt more sustainable ways of producing, processing or distributing food often incur additional costs without benefitting from any money for the social and environmental value generated by their activities. As a result, such businesses generally have to charge a premium for food products, thereby limiting their customer base to those who can afford these commodities. The UK’s food economy can therefore be said to favour less sustainable food production practices.

Breakdown of UK food system externality costs in 2015

Addressing the problem of hidden costs

Currently, there is no universal framework for quantifying and measuring the diverse negative impacts of food systems. By providing a considered estimate of the financial cost of these impacts, this report aims to fill in some of the existing gaps in the data, although it is limited by the lack of reliable data in some areas. In order to create a more accurate picture of the network of food system impacts, there is a need for further academic research on this issue. The Trust believes that such work is crucial to help policy-makers and businesses identify and prioritise those areas of the food system which are most damaging to society. This should also seek to provide a clearer picture of the specific food system impacts in Wales and the other devolved nations.

The authors make three recommendations to the UK Government:

- All aspects of UK agricultural policy post Brexit should be underpinned by an appraisal of the true costs and benefits of different food production systems and techniques;

- Public subsidies should be redirected in a way that will discourage environmentally damaging practices, towards food systems and food types which deliver genuine public goods; and

- Consideration should be given to the use of taxes on the most damaging agricultural inputs. A key example could be the introduction of a tax on each tonne of nitrogen fertiliser, with the income raised used to compensate farmers for the additional costs involved in adopting practices proven to increase soil carbon sequestration.

Integrating true cost accounting into agricultural research and policy development

Clearly, much uncertainty currently surrounds the future of food and farming in the UK. Many stakeholders are advocating policy approaches which encourage food production systems and techniques which deliver tangible public goods. The Trust believes that the hidden costs identified by this study may provide a useful indication of where the greatest public harms lie, enabling policy makers to structure future financial incentives and subsidies in a way that discourages the practices which cause them, and redirect these to greater effect in terms of environmental sustainability and public health.

As mentioned above, the Trust considers that there is a real need for more research on the specific challenges that face food and farming in the devolved nations. Much of the data included in this report is aggregated for England and Wales. A true cost appraisal of the unique food and farming landscape in Wales, with its different impacts and interdependencies, could help to inform discussions around a framework for UK food and farming post Brexit, and ensure that the devolved administrations have a voice in this process.

A summary report (PDF 9.1MB) has been published alongside the full report (PDF 23.9MB).

Article by Emma Rose, Sustainable Food Trust (guest blog post)