This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

The pandemic has drawn attention to the importance of the social care sector, but also demonstrated the fragility of the system. Will COVID-19 be a catalyst for change?

The stark pressures facing the social care sector have been brought into the spotlight during the pandemic.

There’s a new recognition and appreciation of social care staff, but inequalities in how they are treated compared to NHS staff are even more exposed. The need for better support for Wales’ ever-increasing population of unpaid carers has also been highlighted.

It’s widely accepted that fundamental reform of social care is long overdue. There have been numerous Welsh and UK Government papers and reports on reform, but the can has been repeatedly kicked down the road.

The social care workforce

Care work is generally regarded as a low pay, low status profession, with limited opportunities for career progression. The sector suffers from staff shortages, high staff turnover, and major difficulties in recruitment. Social care is consistently losing staff to sectors like retail, which offer better pay and conditions.

56% of the social care workforce in Wales earn below the Real Living Wage (£9.50 an hour). Wages are similar in Wales and England, but markedly higher in Scotland.

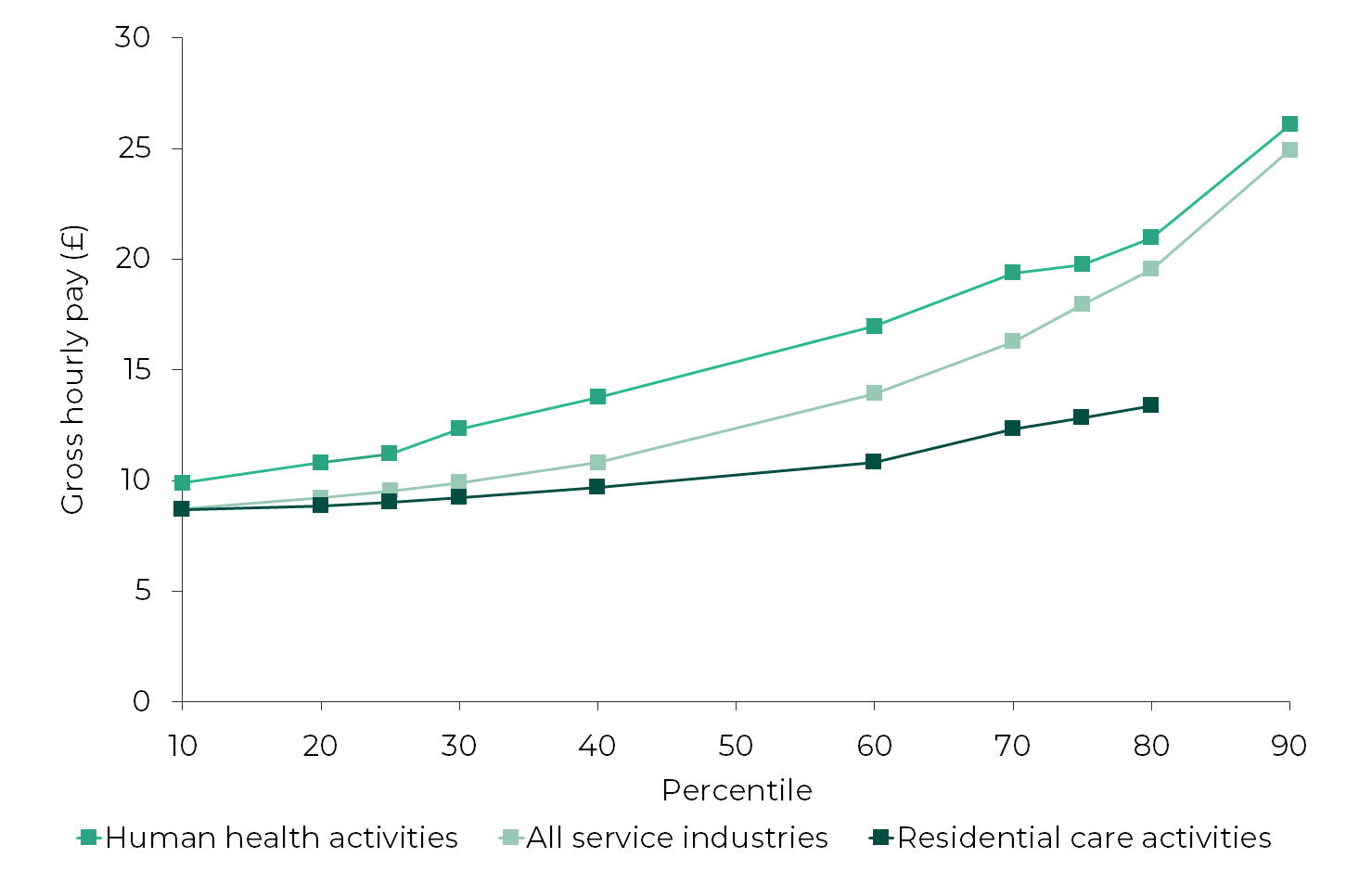

Residential care workers in Wales have faced a decade of no relative improvement in pay, and their median wage remained below the Real Living Wage for most of that period. Wages in residential care are also much lower than the service industry average.

Distribution of gross hourly pay across sectors in Wales; 2020

Source: ONS, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2020, Table 5.5a. Data point for the 90th percentile of residential care workers has been removed as the estimate is deemed unreliable.

During the pandemic the social care workforce faced trauma and significant personal risk, with workers in Wales and England twice as likely to die with COVID-19, compared to the general working-age population.

In March the Fifth Senedd’s Health, Social Care and Sport (HSCS) Committee, alongside stakeholders, called for parity of esteem for social care workers with NHS staff, in terms of pay, working conditions and recognition.

The Social Care Fair Work Forum (a partnership of Welsh Government, employers and unions) concluded later that month that the Real Living Wage should be the minimum pay received by social care workers. It sees this change as the most urgent priority to improve working conditions.

The role of unpaid carers

The majority of care is provided by unpaid carers (typically family or friends) rather than commissioned services. Even before the pandemic it was estimated that unpaid carers provide 96% of all care in Wales.

The replacement cost of care provided by unpaid carers (i.e. purchasing this care at market price) is estimated at £8 billion – roughly the same as the annual NHS Wales budget.

Carers have taken on more caring responsibilities during the pandemic and are now said to be at breaking point, exhausted from long periods of caring without breaks or support. Support services such as respite care, which were already in short supply, have reduced or stopped altogether. Many carers are also struggling financially, and stakeholders want to see greater financial assistance made available.

Any plans for social care reform must recognise the pivotal role of unpaid carers, which isn’t sustainable without improved access to support. As the Fifth Senedd’s HSCS Committee said:

Carers give so much to the people they care for and without them, our health and social care systems would be overwhelmed and unable to function. They must be supported, recognised and rewarded to enable them to continue caring for as long as they wish to do.

The relationship between health and social care

At the start of the pandemic, it was suggested that social care was an afterthought. Vital PPE and access to testing for care workers were significantly delayed in comparison to the NHS.

Patients being discharged from hospitals to care settings (sometimes in the middle of the night) without a negative COVID-19 test result continues to be a cause for concern among stakeholders. The Association of Directors of Social Services (ADSS) Cymru says this has resulted in a significant breakdown of trust between care homes and hospitals. Carers charities also raised concerns about poor hospital discharge practices putting pressure on unpaid carers.

Better integration of health and social care has long been a political ambition but real progress remains to be seen. In 2014, the last Welsh Government established an Integrated Care Fund (ICF), with the aim of driving this forward. However, the Wales Audit Office has been critical of the fund’s overall impact.

Service pressures

The pandemic exacerbated the already precarious financial position of many care providers. And provoked further doubt about the long-term viability of the current service model, particularly within the residential care market.

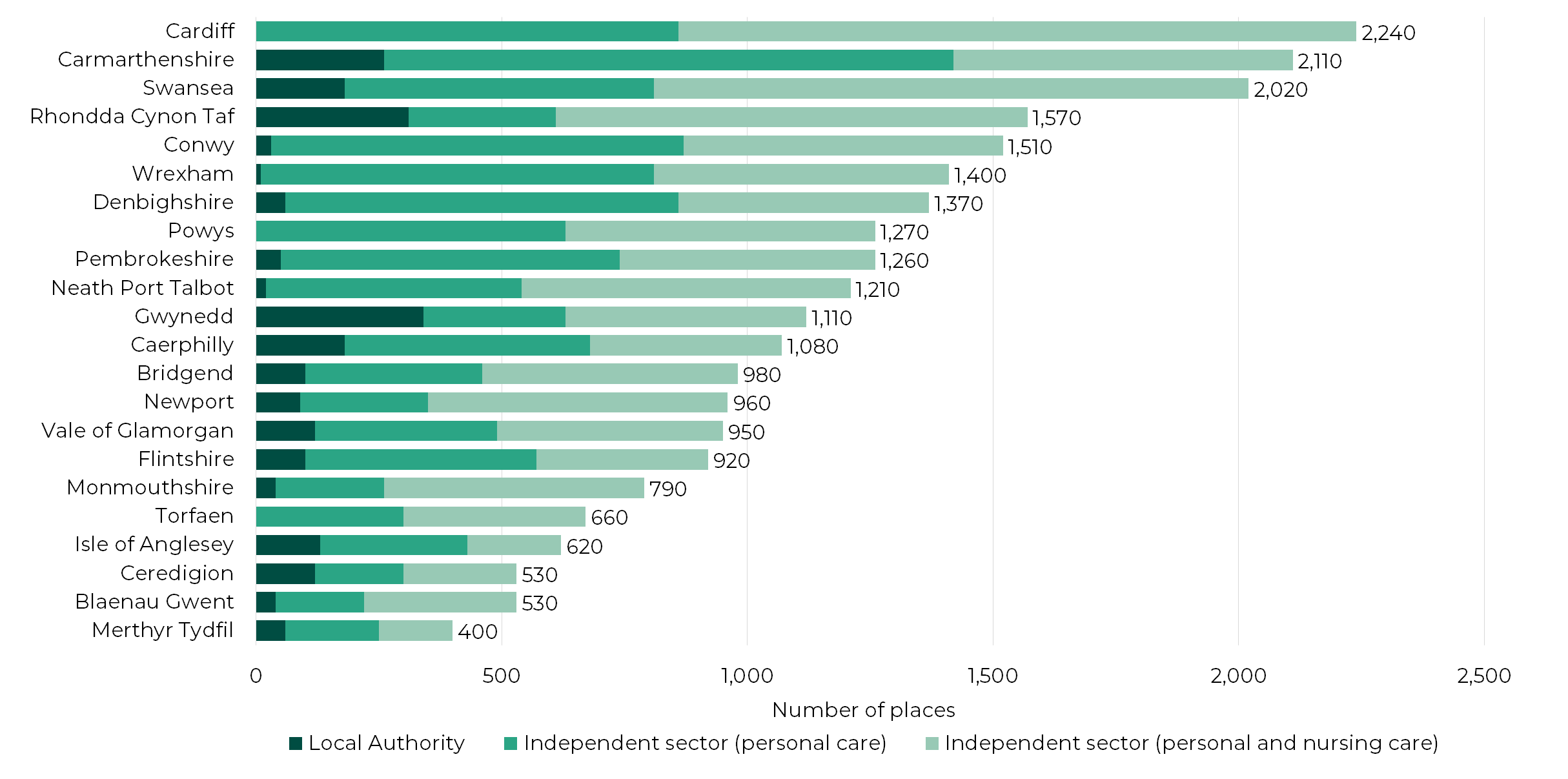

Residential care is extremely fragmented. There are over 1,000 separate care homes, the vast majority of which are small, independent businesses, that provide the lion’s share of adult care home places.

Number of adult care home places, by local authority and provider type; March 2021

Source: Care Inspectorate Wales, March 2021, user requested data. Data rounded to the nearest 10. The full data is available via the data download link.

It’s widely accepted that the care system is underfunded, and local authority fee levels don’t appear to have kept pace with rising costs. Self-funders are effectively subsidising costs, on average paying around 25% more in care home fees than local authorities.

Care homes need a high level of occupancy to be viable but many have seen resident numbers drop during the pandemic, causing significant financial strain.

Care homes have also struggled with serious staff shortages due to illness and staff needing to isolate. In December 2020, a number of care homes reached a critical level of staff absence and were on the brink of closure. According to media reports, residents were close to being moved to hospital because of staffing levels.

Increased demands and pressures also continue to be felt by home care providers, particularly with long COVID and patients who’ve had extended stays in hospital. Looking ahead, long COVID will continue to be a new pressure on services, adding a new group of service users who (without COVID) may not have needed social care.

Future demand

Wales has an ageing population, and people are living for longer with complex care needs and dementia. This will no doubt continue to increase pressure on care services. The number of older adults living with severe dementia is predicted to double by 2040.

Even before the pandemic, the Health Foundation estimated that the Welsh social care budget would need to reach £2.3 billion by 2030/31 to match demand.

The previous Minister for Health and Social Services, Vaughan Gething, acknowledged that Wales’ already stretched services won’t meet future demand unless action is taken. He reported that spend on social services could be up to £400 million higher in 2022-23, just to maintain the current level of services.

The last Welsh Government concluded that radical reform to improve social care wasn’t likely in the near future, given the challenging economic climate caused by the pandemic.

The then Minister said that, in the shorter term, measures “working towards introducing a real living wage for the workforce” could be implemented “as quickly as is affordable”.

As the Nuffield Trust notes, COVID-19 has pushed the demand for reform up the agenda:

Never has social care been so prominent in public and political discussions. There is a groundswell of support for reform that presents a rare opportunity to achieve tangible change.

Will this translate into action to improve social care by the next Welsh Government?

Article by Amy Clifton, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament