Probation plays an important role in the justice system. It allows people who have committed crimes to serve their sentences in the community under supervision, rather than in prison. This approach aims to protect the public by managing any risks offenders pose, while addressing the root causes of offending.

Probation Officers help individuals access services such as housing, employment, and mental health support, helping them rebuild lives and reduce the risk of reoffending.

In Wales, many of these services —health, housing, and substance misuse - are already devolved, which many argue strengthens the case for closer integration and, ultimately, the devolution of probation powers. This article explores why that debate matters and what options are on the table.

Why the service is under pressure

Despite its importance, probation in England and Wales has faced decades of upheaval. Repeated reforms have left the service fragile and struggling to achieve stability.

One of the most significant changes was the Transforming Rehabilitation programme introduced in 2014. This reform split probation between public and private providers, with private sector-led Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) managing low- and medium-risk cases from February 2015. The model was widely criticised for poor performance and dismantled between 2019 and June 2021, when services were reunified under the Probation Service.

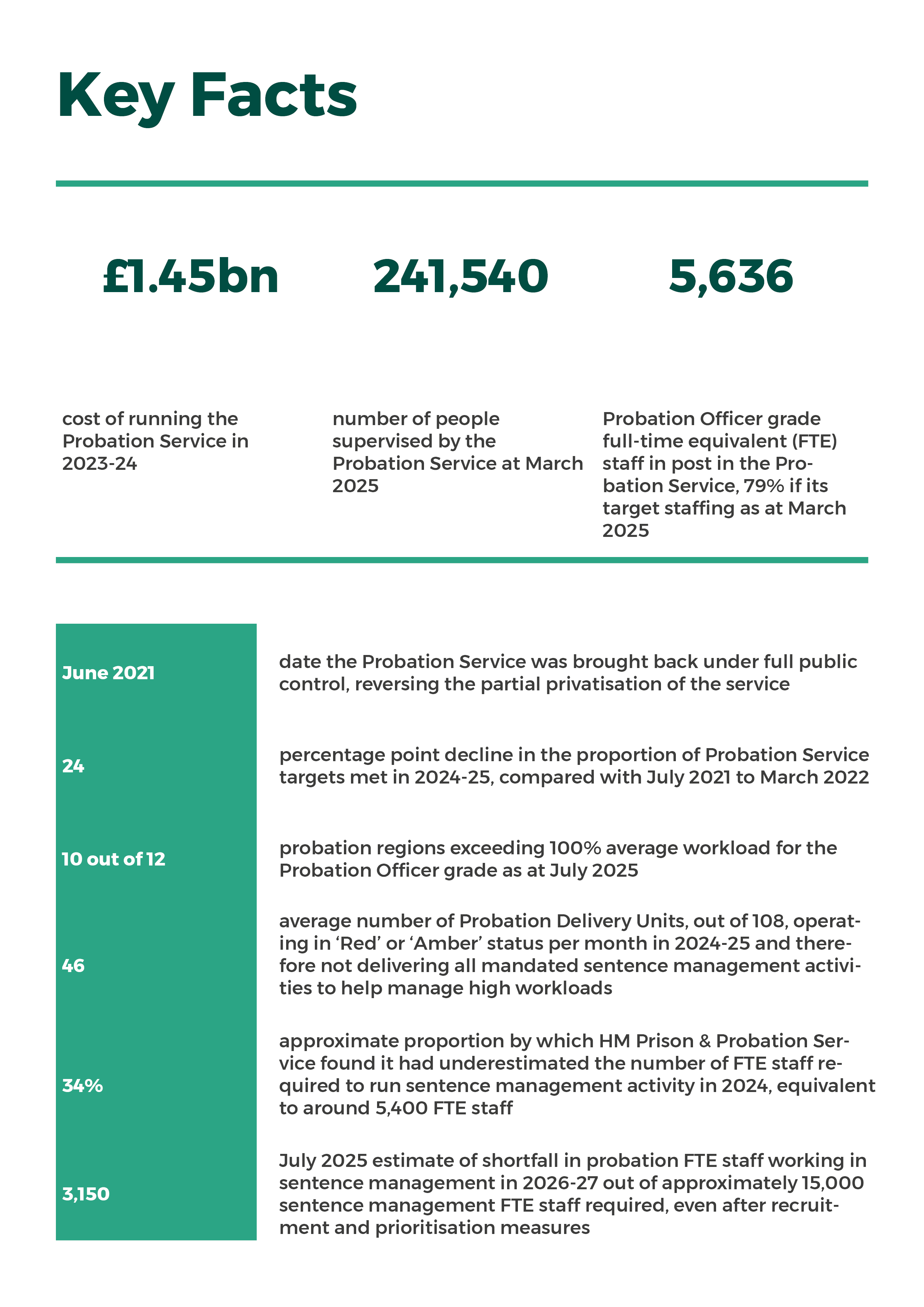

While heavy caseloads have long been a feature of probation work, the upheaval caused by these reforms has compounded operational pressures and continues to affect the service’s ability to deliver effectively. A substantial proportion of regions are “Red” or “Amber” for performance. HM Inspectorate of Probation continues to rate the service as “requires improvement.”

Source: National Audit Office

The National Audit Office has warned that repeated restructuring has undermined resilience and left the service ill-prepared for further change. This context was highlighted recently by UK Minister Lord Timpson (Minister of State for Prisons, Probation and Reducing Reoffending ) during his meeting with the Senedd’s Equality and Social Justice Committee, where he stressed the importance of stability before pursing any major constitutional. Changes.

The UK Government’s position

Lord Timpson told the Committee that devolving probation to Wales is not a priority for him while the justice system faces “massive pressures”. He described the Probation Service as “bruised” from previous reforms, and said it must be stabilised before “further changes” are considered.

Lord Timpson did not rule out devolution, but avoided committing to a timeline. Instead, he pointed to partnership working—through joint commissioning and formal agreements—as the preferred route, rather than the immediate transfer of legislative powers.

This approach mirrors the model used in Greater Manchester, where the Mayor has more practical influence over probation than Welsh Ministers.

Under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Ministry of Justice, Greater Manchester can co-commission probation-related services, such as housing support or drug treatment programmes, tailored to local needs. For example, if data shows high reoffending linked to homelessness, the Mayor can fund a housing initiative alongside probation services. This flexibility allows Manchester to respond to local priorities, even though the core probation service remains national.

By contrast, Welsh Ministers currently have no formal powers over probation. They cannot set budgets, change operating models, or legislate for a Welsh probation service. Their influence is limited to partnership working and joint initiatives. This imbalance—where a city-region has more say than a devolved nation—has become a focal point in the debate.

The Welsh Government’s position

The Welsh Government has long argued for full legislative and executive control over probation. The Cabinet Secretary for Social Justice, Jane Hutt MS, told the Senedd Committee that the Welsh Government has been preparing for this for more than four years and insists progress is being made. However, she recognises that change must be phased.

In August 2025, the Welsh Government issued a written statement confirming discussions with the then Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Shabana Mahmood MP about youth justice realignments and an MoU on probation—explicitly “similar to the model in place in Greater Manchester.” This suggests a pragmatic approach: begin with administrative arrangements, while preparing for constitutional devolution.

Options for devolution

To support its preparations, the Welsh Government commissioned the Wales Centre for Public Policy (WCPP) to examine practical delivery options. Its 2024 report, Building a Welsh Probation Service, sets out three pathways:

- MoU and co-commissioning of certain services (as in Greater Manchester);

- Transfer of executive responsibility without legislative competence, giving Welsh Ministers administrative oversight but no law-making power; and

- Full legislative and executive responsibility, enabling the Senedd to create a Welsh probation service.

The report highlights the benefits of devolution: better integration with devolved services, opportunities to redesign operating models and workforce conditions, and clearer accountability. It also flags challenges such as workforce planning, cross-border issues, and interfaces with reserved services like prisons.

The WCPP frames devolution as a means to enhance probation performance, not an end in itself. It says aligning supervision with health, housing, and social services that the Senedd already controls, could tackle criminogenic needs (the personal factors or circumstances that increase the likelihood of someone committing crime) more effectively.

In parallel, the Probation Development Group (PDG)—a network of Welsh academics and practitioners—has published evidence arguing that the current model is not working and that Welsh-aligned probation could improve public safety and rehabilitation outcomes.

Where does this leave Wales?

Full legislative and executive devolution would require UK legislation and political agreement. The case has been made by multiple commissions, including the Thomas Commission and the Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales, but timing appears to be the main barrier.

For now, the UK Government favours an incremental approach, using Greater Manchester as a template. The Welsh Government appears willing to start there, while keeping the door open to full constitutional change.

Probation in Wales sits at the intersection of justice and social policy. Its future depends on balancing ambition with pragmatism, and for now both governments seem to agree that starting with a MoU and co-commissioning is the practical next step.

Whether this approach will pave the way for full devolution—or settle into a long-term compromise that leaves Wales without the powers it seeks —will depend on political will and proof that closer integration improves public safety and rehabilitation outcomes.

|

This article is part of a series exploring key aspects of criminal justice in Wales, from the current devolution settlement and intergovernmental working, to probation, youth justice policy, and policing. |

Article by Sarah Hatherley, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament

Sentencing Reforms: What’s changing and why it matters for Wales

A deserted landscape: access to criminal legal aid in Wales (Part 1)