Article by Michael Dauncey, National Assembly for Wales Research Service

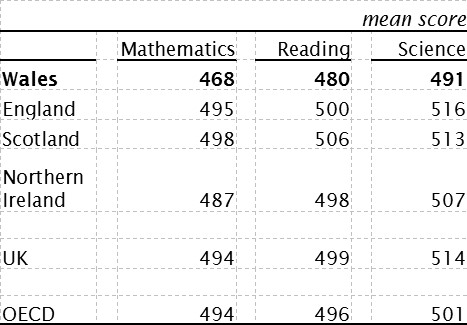

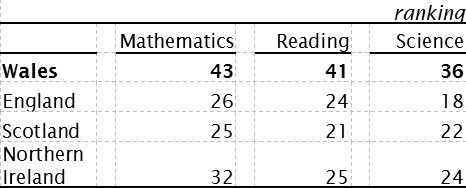

This afternoon, Assembly Members will debate an opposition party motion on education strategy and policy in Wales. Part of the motion refers to educational outcomes in the ‘key areas of reading, mathematics and science’, which are the three domains of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). This article provides some background on Wales’ PISA results and the influence that UK and international comparisons are having on the Welsh Government’s education policies. (It does not seek to address all other points raised by the Plenary motion.) PISA, which is run by the OECD, measures the aptitude of pupils in around 65 countries across the world in the three domains of reading, mathematics and science. It does this based on the scores achieved in tests by a sample of 15 year olds from each participating country. It is generally accepted that Wales has not scored well in recent PISA cycles and this has had a big effect on the direction and policy of the Welsh Government. In late 2010 and early 2011, the then Minister for Education, Leighton Andrews, described Wales' PISA 2009 results as a ‘wake up call to a complacent system’ and launched a 20 point plan centred around a renewed focus on literacy and numeracy. The Welsh Government stressed during the run up to the publication of the PISA 2012 results that the 2015 cycle would be the true test of the impact of its school improvement reforms. Whilst the Minister for Education and Skills, Huw Lewis, said the 2012 results therefore ‘present[ed] no surprise’, he accepted they ‘were not good enough’ and asserted that they confirmed the Welsh Government’s view that ‘standards are not high enough and must improve’. He also asked for ‘everyone in and around the educational sector to take a long hard look in the mirror’. Wales’ PISA results We published a Research Note (pdf 289KB) when the PISA 2012 results were published in December 2013, which provided an overview and some trends and analysis, including PISA’s influence on Welsh Government policy. Wales’ scores (and therefore its rankings) in each of the three domains are lower than those for England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland in all cases. In each of the domains, the difference is statistically significant. Table 1 below presents the PISA 2012 scores for different parts of the UK in each of the three domains, whilst Table 2 gives the rankings. Table 1: PISA 2012 scores  Table 2: PISA 2012 rankings

Table 2: PISA 2012 rankings  Source: National Foundation for Educational Research, Achievement of 15 year olds in Wales: PISA 2012 National Report, 2013 Note: These rankings are based on excluding the UK as a whole and including the four individual nations. Ranking is therefore in the context of 68 participating countries. The OECD’s report Not long after, in April 2014, the OECD published its review of Wales’ education system (pdf 3.75MB), which was commissioned by the Welsh Government. This identified four strengths and four related challenges, as well as 14 policy options. Chapter 1 of the report documented the OECD’s findings, the conclusion section of which stated: ‘Policy making and implementation can be strengthened, as the pace of reform has been high, sometimes too high, and lacks a long-term vision. The school improvement infrastructure is underdeveloped and lacks a clear implementation strategy for the long run.’ The Welsh Government had already intended to update its education improvement plan in the autumn of 2014 but published Qualified for Life also in the context of the OECD’s report. As well as refreshing and updating reforms already planned or in progress, the revised plan addresses the OECD’s critique. The PISA ambition Following the PISA 2009 results, the Welsh Government set an aim that Wales would be in the top 20 PISA nations by the 2015 cycle. However, since PISA 2012, it has reframed its aspirations, switching to an absolute ambition of 500 points in each domain by 2021, rather than one relative to the performance of other nations. The OECD had been quite critical of the top 20 aim, saying that it was not wholly within the Welsh Government’s gift or control. The Minister argued the new (500 points) ambition was ‘hardly less stretching’ than the previous (top 20) aim, with the scale of improvement required fairly similar (albeit slightly lower for Reading and Science). The main difference is the timescale; the Welsh Government is allowing nine more years and three PISA cycles to achieve its 500 points ambition, as opposed to three further years and one cycle under its previous top 20 aim. How important is PISA? PISA is generally regarded as a valuable and useful tool of comparing different education systems and enabling countries to assess their position relative to their international counterparts. However, there are also some critics of the programme. In May 2014, The Guardian reported that a group of academics around the world wrote to the OECD’s Andreas Schleicher, widely seen as the architect of PISA, arguing that the reliance and importance placed on PISA results was distorting governments’ education policies. Here in Wales, the Minister acknowledged such observations in his statement of 10 December 2013 but stressed: ‘The reason why this Government places so much store on PISA is that it assesses learners’ ability to tackle real life situations; it is not a test of the curriculum. As young people do not spend their whole time in school, I want them to have the skills to find solutions to everyday problems’. GCSE performance Of course, it’s not all about PISA as GCSE and A/AS level results continue to be used to compare Wales’ performance with other UK nations. These more traditional methods of measuring young people’s academic ability continue to test a ‘mastery of the curriculum’ as the National Foundation for Economic Research (pdf 5.10MB) put it. The Welsh Government has highlighted this year’s ‘best ever GCSE results’ and that ‘pupils from less well off backgrounds are closing the gap with their class mates’. Despite this, a gap in GCSE achievement persists between Wales and England in English language and Mathematics, although this has narrowed in recent years.

Source: National Foundation for Educational Research, Achievement of 15 year olds in Wales: PISA 2012 National Report, 2013 Note: These rankings are based on excluding the UK as a whole and including the four individual nations. Ranking is therefore in the context of 68 participating countries. The OECD’s report Not long after, in April 2014, the OECD published its review of Wales’ education system (pdf 3.75MB), which was commissioned by the Welsh Government. This identified four strengths and four related challenges, as well as 14 policy options. Chapter 1 of the report documented the OECD’s findings, the conclusion section of which stated: ‘Policy making and implementation can be strengthened, as the pace of reform has been high, sometimes too high, and lacks a long-term vision. The school improvement infrastructure is underdeveloped and lacks a clear implementation strategy for the long run.’ The Welsh Government had already intended to update its education improvement plan in the autumn of 2014 but published Qualified for Life also in the context of the OECD’s report. As well as refreshing and updating reforms already planned or in progress, the revised plan addresses the OECD’s critique. The PISA ambition Following the PISA 2009 results, the Welsh Government set an aim that Wales would be in the top 20 PISA nations by the 2015 cycle. However, since PISA 2012, it has reframed its aspirations, switching to an absolute ambition of 500 points in each domain by 2021, rather than one relative to the performance of other nations. The OECD had been quite critical of the top 20 aim, saying that it was not wholly within the Welsh Government’s gift or control. The Minister argued the new (500 points) ambition was ‘hardly less stretching’ than the previous (top 20) aim, with the scale of improvement required fairly similar (albeit slightly lower for Reading and Science). The main difference is the timescale; the Welsh Government is allowing nine more years and three PISA cycles to achieve its 500 points ambition, as opposed to three further years and one cycle under its previous top 20 aim. How important is PISA? PISA is generally regarded as a valuable and useful tool of comparing different education systems and enabling countries to assess their position relative to their international counterparts. However, there are also some critics of the programme. In May 2014, The Guardian reported that a group of academics around the world wrote to the OECD’s Andreas Schleicher, widely seen as the architect of PISA, arguing that the reliance and importance placed on PISA results was distorting governments’ education policies. Here in Wales, the Minister acknowledged such observations in his statement of 10 December 2013 but stressed: ‘The reason why this Government places so much store on PISA is that it assesses learners’ ability to tackle real life situations; it is not a test of the curriculum. As young people do not spend their whole time in school, I want them to have the skills to find solutions to everyday problems’. GCSE performance Of course, it’s not all about PISA as GCSE and A/AS level results continue to be used to compare Wales’ performance with other UK nations. These more traditional methods of measuring young people’s academic ability continue to test a ‘mastery of the curriculum’ as the National Foundation for Economic Research (pdf 5.10MB) put it. The Welsh Government has highlighted this year’s ‘best ever GCSE results’ and that ‘pupils from less well off backgrounds are closing the gap with their class mates’. Despite this, a gap in GCSE achievement persists between Wales and England in English language and Mathematics, although this has narrowed in recent years.

- In the summer 2015 results, 67% of pupils achieved a grade A*-C in English language compared to 74% in England.

- In Mathematics, 66% achieved grade A*-C in Wales whereas 70% did so in England.

- However, when using Welsh language GCSE as a comparator, pupils in Wales fare as well as in England, with 74% achieving a grade A*-C. Over recent years, the A*-C rate has actually been higher for Welsh language GCSE in Wales than for English language GCSE in England.

(Note: the data in England is provisional, whereas the Welsh Government has recently published final data in Wales.) The motion to be debated in the Chamber is available on the Assembly’s website and the proceedings can also be viewed on Senedd TV (scheduled for approximately 5.00pm).