This article is part of our 'What's next? Key issues for the Sixth Senedd' collection.

The landscape of inequality exposed by the pandemic largely followed the contours of existing disadvantage. But will previous approaches to reducing inequality be enough to counter these stark imbalances, or will new strategies be needed? And what role does data - or the lack of it - play?

The language of equality is used across the political spectrum, from ‘social mobility’ to ‘levelling up’, and ‘intergenerational fairness’ to ‘social justice’. At the core is the idea that some people, groups, or areas are disproportionately or unfairly advantaged - whether economically, socially, culturally, or politically – because of systems and structures that enable it.

The pandemic has brutally demonstrated what these inequalities mean for people’s lives on a scale not previously seen. Our chances of dying, getting seriously ill, losing jobs, experiencing abuse, or falling behind in education have been in part determined by who we are, our finances, our health, and where we live.

These factors, intertwined with others like adequate housing, the ability to home-work, and access to childcare, a car, outside space, and reliable internet, act to increase or decrease disadvantage.

And it leads us to ask a fundamental question: is this fair?

If not, what kind of policy interventions and systemic changes are needed to close the gaps?

Why is inequality a problem?

We often hear that a rising tide of economic growth lifts all boats. But in reality, a rising tide of inequality sinks all boats. […] From the exercise of global power to racism, gender discrimination and income disparities, inequality threatens our wellbeing and our future.

United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres

Inequality is increasingly a problem for us all. It’s estimated to cost the UK £39 billion a year, as managing the outcomes, like homelessness, are usually costlier than prevention. And while domestic abuse was recently estimated to cost the UK £66 billion a year, achieving economic gender equality could boost Wales's economy by nearly £14 billion.

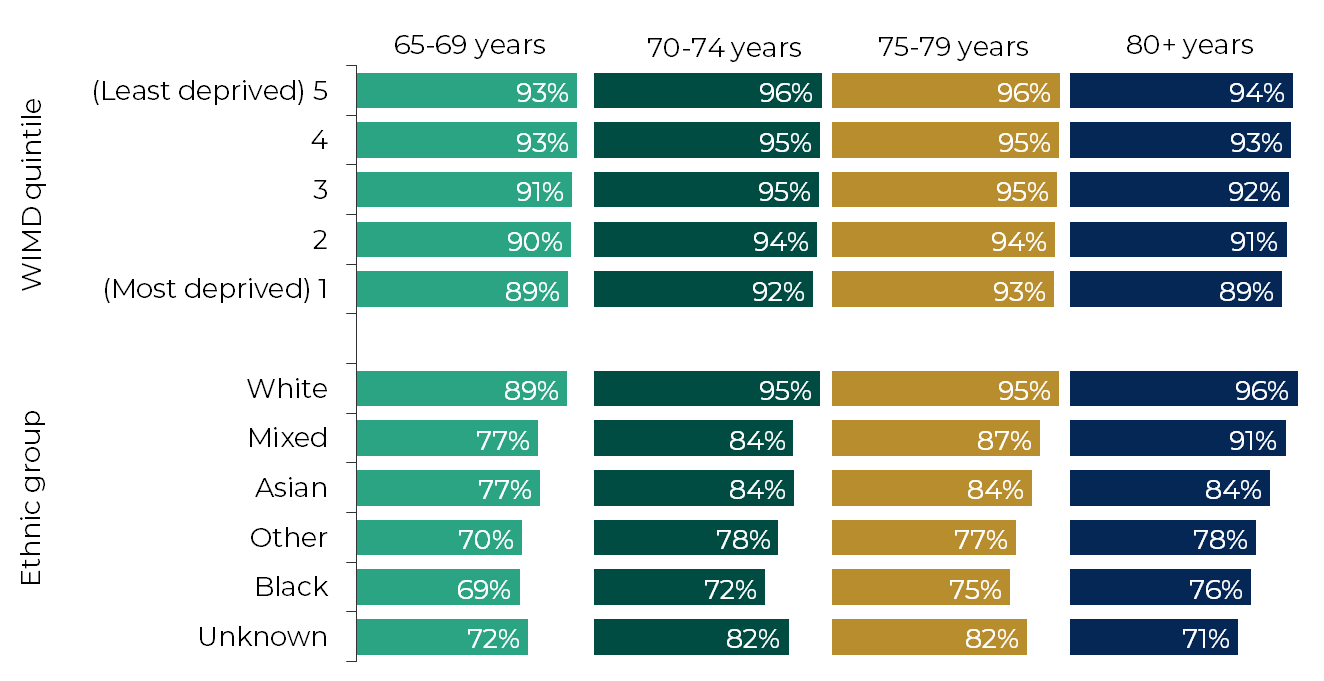

Inequality might also slow down post-pandemic recovery. The lower take-up of vaccines among some ethnic groups and those living in the most deprived areas are of particular concern. Targeted misinformation, and long-term distrust of public authorities linked to structural and institutional racism and discrimination, are likely causes that will need more than a public engagement campaign to solve.

Vaccination rates by WIMD quintile, ethnic group and age

Source: Public Health Wales: Wales COVID-19 Vaccination Enhanced Surveillance Report 2

Equal treatment or equal outcomes?

Inequalities can be reduced either through universal policies that treat everyone the same, or by targeting them at those most in need.

Proponents of ideas like a universal basic income (UBI) argue the pandemic has shown that resources for comprehensive social protection for everyone can be found. Others contend that ‘positive action’, which favours certain groups, helps to equalise outcomes by addressing historic disadvantage. ‘Proportionate universalism’ is somewhere in between, where services are available to all but with effort targeted where it’s most needed.

During the pandemic, some policies were targeted at people at higher risk based on their vulnerabilities. These include the ‘shielding’ programme, which recognised deprivation and ethnicity as risk factors in England, and the Welsh workforce risk assessment tool, which used demographics and health conditions to create a ‘risk score’ and suggested mitigation measures.

The previous Welsh Government also launched a benefits take up campaign aimed at those most in need of financial support, and a helpline specifically for people from ethnic groups disproportionately affected by the virus.

What don’t we know?

Absence of evidence isn’t evidence of absence. If interventions are targeted at those who lost the most in the crisis, it’s important that no-one is left uncounted.

In 2020 a Senedd committee voiced concerns about the poor quality of equality data available in Wales. This was echoed by the House of Commons Women and Equalities Committee, which specifically called for the collection of redundancy data disaggregated by sex, ethnicity, and other characteristics.

We also know that where these factors intersect, inequalities are amplified. Some groups were hit particularly hard by lockdown, when 39% of all female employees under 25, and 44% of workers of Bangladeshi ethnicity, were working in shut-down sectors in Wales.

Overlaying this data allows for a more nuanced understanding of risk, power, wealth, security, need, and experience, rather than treating broad demographic groups as homogenous. The previous Welsh Government repeatedly emphasised its intersectional approach to equality. But a lack of disaggregated, intersectional data frustrates meaningful analysis.

The collection of personal data by public authorities is sensitive, and requires trust. And targeting policies at certain groups can be seen as tokenistic or even discriminatory. These issues may present challenges for policy design in the coming years.

Are the tools up to the job?

The reduction of inequalities was at the core of the previous Welsh Government’s COVID-19 plan for recovery. It also set bold ambitions to become a ‘feminist government’, and a ‘world leader for gender equality’.

In March 2021, the Socio-economic Duty was commenced in Wales. It requires most public authorities to consider how they can improve outcomes for people on low incomes when making strategic decisions.

This will sit alongside the existing public sector equality duties, which compel Welsh public authorities to do things like conduct equality impact assessments, develop equality plans and objectives, and collect equality data. The Well-being of Future Generations Act also requires public authorities to think about the long-term impact of their decisions on equality and cohesion.

But it’s difficult to measure the effectiveness of these duties. If inequalities in a particular policy area are not decreasing, does it indicate that the duty isn’t being fulfilled, or that it isn’t working? What if the levers of change aren’t devolved? And if an impact assessment uncovers an unfair impact, is there a duty to act on it? Does this approach make sure we collect quality data?

With such unambiguous and widening inequalities at the forefront of political debate, the new Welsh Government will have to decide if previous approaches will work in the post-pandemic world.

The Sixth Senedd will also be critical in challenging the new Welsh Government to show how it’s translating big ambitions on equality into tangible change.

Article by Hannah Johnson, Senedd Research, Welsh Parliament